The Freedom Flotilla: Solidarity and Resistance in Gaza’s Crisis

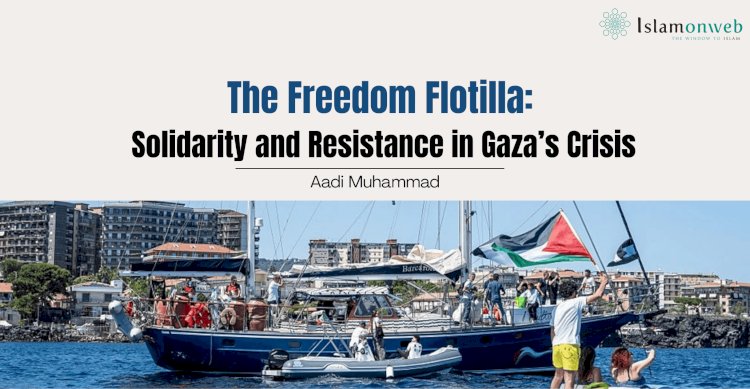

In early 2025, a new “Freedom Flotilla” sailed from Turkey toward Gaza, challenging Israel’s maritime siege. On 2 May 2025, the flotilla’s aid ship Madleen (also called Conscience) was struck by armed drones in international waters off Malta, causing a breach and fire as the vessel carried humanitarian supplies. Activists reported that the incident occurred amid a “two-month total blockade” imposed by Israel on Gaza.

This essay examines the flotilla raid in context: it traces the longue durée of Palestinian dispossession (the Nakba of 1948 and its aftermath) and past Gaza aid efforts (notably the 2010 Mavi Marmara raid), and then analyses the episode through Islamic ethics and international law.

We show how Qur’anic principles—such as the call to defend the oppressed (Q. 4:75)—and concepts like ‘adl (justice), raḥma (mercy), and ummah (community) inform Muslim solidarity with Gazans, while international humanitarian law (e.g., Fourth Geneva Convention Articles 33 and 55) forbids collective punishment and obliges the delivery of relief. Drawing on scholars like Richard Falk and voices from civil society, we cast the flotilla as a form of transnational nonviolent resistance, echoing the global mobilisations of the anti-apartheid movement.

Historical Roots

The Gaza blockade must be seen in light of decades of Palestinian displacement. The Nakba of 1948 (“Catastrophe”) saw roughly 750,000 Palestinians expelled from their ancestral lands. As the UN notes, the 1948 dispossession “continued to this very day,” with Gaza now described as under siege by blockade and bombardment, amounting to a “second Nakba.” In 1967, Israel occupied Gaza (and the West Bank), and in 2007 it imposed a land, air, and sea closure on Gaza after Ḥamās took power.

Over the past decade, Israel’s naval blockade has become notorious. For example, on 31 May 2010, Israeli forces raided a Turkish-led Gaza aid flotilla (the Mavi Marmara) in international waters. Nine activists were killed, provoking global outrage. UN and human rights bodies condemned the raid as a violation of international law; Special Rapporteur Richard Falk called the Gaza blockade “a massive form of collective punishment” and urged its end. Since then, international flotillas and aid convoys have repeatedly attempted to challenge Israel’s siege, often being blocked or attacked.

In 2025, as Gaza reeled from another war (following Ḥamās’s October 2023 attack) and faced an intensifying embargo, a new Freedom Flotilla was formed. Its ship Madleen (formerly a sardine trawler) picked up 30 Turkish and Azeri activists en route to Gaza. According to a statement by the Freedom Flotilla Coalition, the vessel was struck twice by drones around 25 km off Malta, causing fire and hull damage. Activists said they had sent an SOS and that Maltese authorities intervened; thankfully, all on board were evacuated safely, though the ship eventually sank.

The episode revived memories of past aid missions: Madleen was described as seeking to “break Israel’s blockade,” as earlier Gaza-bound ships had attempted. In sum, the 2025 incident is part of an ongoing pattern: decades of Palestinian exile and siege, punctuated by international solidarity flotillas attempting to deliver relief and assert Gaza’s rights.

Islamic Framework

Islamic teaching places great emphasis on aiding the oppressed and upholding justice. The Qur’an explicitly commands believers to fight “in the cause of Allāh and [for] the oppressed among men, women, and children” (Q. 4:75). This verse enjoins the Muslim community (ummah) not to remain indifferent when innocents are tyrannised. Gaza’s plight recalls these words: citizens pleading “Our Lord, rescue us from this town of oppressors” are like the early Muslims beseeching deliverance—and Islam commands us to answer such calls.

Likewise, the Qur’an warns: “Do not say of those who are killed in the way of Allāh that they are dead; they are alive, but you are not aware” (Q. 2:154). This verse honours shahādah (martyrdom), affirming that those who die defending their people are spiritually alive. The notion of shahādah imbues courage and sustains hope amid suffering. Commentators have noted that Gazans enduring bombardment echo the trials of the Prophet’s ﷺ companions under Meccan persecution. As Islam21c observes, just as the early Muslims survived a multi-year boycott (living on rainwater and leaves), today Gazans “brave the conditions” under siege. In both cases, a small community faced overwhelming oppression, yet relied on faith and solidarity.

Islamic ethical thought also stresses ‘adl (justice) and raḥma (mercy). The Prophet ﷺ taught Muslims to be “fair and just at all times, even if it involves going against your self-interests.” By extension, Islamic justice entails calling out injustice—whether against Muslims or others—and showing mercy toward victims. The Qur’anic ideal of raḥma permeates scripture: Allah is repeatedly described as ar-Raḥmān, ar-Raḥīm. Islam thus forbids cruelty and the starvation of innocents.

Abū Ḥanīfa, al-Ghazālī, and other jurists emphasised that the ummah must support one another in hardship. As al-Ghazālī noted, Muslims should be a unified ummah that “is supportive of each other… creating a network of support.” Early Islamic teachings also hold defenders of justice in high regard: believers are exhorted that if the community stands up for Allāh (in defence of truth), “He will help [you] and make your steps firm” (Q. 47:7). The steadfastness of Gazans in the face of bombardment is thus seen as embodying these prophetic ideals of patience (ṣabr) and faith. As the Islam21c author reminds, the suffering of Gazans echoes the Prophet’s ﷺ ordeal, and “their reward is with Allāh.”

In summary, from an Islamic standpoint, the blockade and attacks against Gazans violate core values. Muslim ethical tradition—rooted in Qur’ān and Prophetic example—mandates aiding the weak (Q. 4:75) and honours sacrifice for justice (Q. 2:154). It denounces oppression and calls upon the ummah to respond with compassion. As al-Ghazālī stated, believers have six mutual rights, including helping one another, visiting the sick, and loving for others what one loves for oneself. These teachings suggest that apathy is betrayal—and that standing with Gaza’s embattled population is a sacred duty, reflecting ‘adl and raḥma as divine commands.

Legal Dimensions

Under international law, Israel’s Gaza blockade and related actions raise serious legal concerns. Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits collective punishment of civilians: “No protected person may be punished for an offense he or she has not personally committed. Collective penalties… and all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited.” The ICRC mission on the 2010 flotilla concluded that one aim of the blockade was to “punish the people of Gaza” for having elected Ḥamās, and judged that the blockade thus amounted to unlawful collective punishment. Human Rights Watch similarly states that “cutting off food, water, electricity, and fuel” to Gaza constitutes collective punishment of a civilian population—a war crime under the laws of war.

Notably, UN bodies and legal experts have repeatedly affirmed that the deprivation of basic necessities such as food and medicine is illegal under the law of occupation. In particular, Article 55 of the Fourth Geneva Convention obliges an occupying power to ensure the provision of food and medical supplies to the population; Article 59 makes this duty unconditional. From March 2024, Amnesty International reported that Israel’s blockade—and its refusal to allow aid into Gaza—flagrantly violates these provisions, with catastrophic humanitarian consequences.

Under the laws of naval warfare, a blockade must meet strict legal criteria: it must not be aimed at starving civilians, and it must be enforced impartially. A blockade that causes “disproportionate damage” to civilians in relation to the anticipated military advantage is unlawful. The ICRC has noted overwhelming evidence that Gaza’s closure has inflicted such disproportionate harm upon the civilian population. In other words, international law prohibits the use of starvation as a weapon and demands that even wartime actions avoid targeting civilians.

The Madleen’s presence in international waters also implicates the San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea. According to its provisions, a neutral vessel on the high seas may not be attacked or seized unless it is clearly breaching a lawful blockade. Since the legality of Israel’s blockade is widely contested, most jurists argue there was no legal basis for forcibly stopping or striking an unarmed aid ship such as Madleen.

Finally, under the law of occupation, Israel is widely regarded as bearing responsibility for Gaza’s civilian population. Even where the occupation status is debated, the humanitarian obligations of the occupying power apply “as long as the population remains dependent on it” for essential needs. Human rights law also applies at all times, requiring the occupying power to ensure humane treatment and the provision of basic services. In practice, major international actors—from the ICRC to UN Special Rapporteurs—have described Gaza’s blockade as collective punishment and potentially amounting to unlawful starvation. Richard Falk, for example, has referred to it as “genocide by starvation” in effect.

In sum, under international humanitarian law and the laws of occupation, the deliberate denial of aid and starvation of a civilian population is categorically forbidden. On this basis, Israel’s blockade and its maritime interdictions, including the 2025 flotilla incident, appear prima facie illegal.

Contemporary Implications

The 2025 flotilla exemplifies the rise of transnational civil resistance in support of Gaza. Activists from multiple countries are now regularly mobilising to break the siege or highlight injustice, much as during the anti-apartheid era. South African activist Ziyaad Lunat explicitly drew the analogy, calling BDS (boycott, divestment, sanctions) a movement “reminiscent of the anti-apartheid movement.” Indeed, within hours of the 2010 raid, protests erupted worldwide, and since then, student and faith-based groups have organised to press for Gaza’s rights. In 2025, even noted activist Greta Thunberg was reportedly briefly detained by Israeli forces during an aid ship seizure.

Scholars like Richard Falk have praised and encouraged these efforts. Falk stated in 2010 that the BDS campaign against Israel had become a “moral and political imperative” to end the blockade. He and others frame Gaza as a global justice issue, paralleling colonial and apartheid struggles. In mid-2025, Falk helped launch a “Gaza Tribunal” in Sarajevo, explicitly comparing Gaza to past genocides and urging worldwide nonviolent pressure on Israel.

Ayhan Kaya, a scholar of Turkish migration and diaspora, similarly observes that Muslim communities worldwide are increasingly politicised by Gaza’s plight, using digital networks to organise solidarity campaigns. Kaya notes how transcultural Muslim identity now fuels public diplomacy and humanitarian initiatives for Palestine. This transnational solidarity means that a ship like Madleen carries not just goods, but the hopes of a global ummah. The flotilla’s participants and supporters in Europe and beyond deliberately evoke both prophetic and legal narratives: they cite Qur’anic calls to resist oppression and reference international law’s ban on collective punishment—acting, in effect, as conscience-keepers.

Thus, the Freedom Flotilla movement can be seen as a new vector of people-powered justice. It deliberately invokes parallels with apartheid and colonial liberation: dockworkers refusing to unload Israeli cargo, academic conferences on the Nakba, and artists equating Gaza with historic struggles. As one UN panellist remarked in 2024, the Palestinian Nakba and South African apartheid were “enabled by Western colonial interests,” suggesting that the moral logic of solidarity is the same. The Gaza flotillas are part of a broader global justice movement that includes BDS and nonviolent protest, aiming to “challenge the survival of an entire beleaguered community.” For many Muslims, this struggle is not only political but sacred, resonating with the Qur’anic promise: “O believers! If you stand up for Allah, He will help you and make your steps firm” (Q. 47:7).

The 2025 Freedom Flotilla incident off Malta must be read as both a continuation of Palestinian history and a living application of Islamic and international principles. From the Nakba of 1948 to the present siege of Gaza, Palestinians have endured dispossession and blockade. Yet Islamic ethics—the Qur’ān, the Prophet’s ﷺ example, and scholars like al-Ghazālī—compel Muslims to resist oppression (‘adl) with compassion (raḥma), to honour those who sacrifice (shahādah), and to unite as an ummah. At the same time, established norms of humanitarian law condemn collective punishment and mandate relief for the starving.

In this light, the flotilla’s attempt to deliver aid and assert Gazans’ rights is not only legitimate but morally and legally justified. As Richard Falk and others conclude, it is incumbent upon global civil society to support these efforts, for “to stand idly by” amid Gaza’s suffering is to betray both justice and mercy. The flotilla movement thus exemplifies a transnational resistance rooted in sacred values and universal law—a bold assertion that the collective conscience will not allow Gaza’s blockade to stand.

About the author

Aadi Muhammed, An anthropology student at Indira Gandhi National Open University, is passionate about academics and exploring human cultures.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment