Alchemy of Hunger

To be empty of worldly food is the precondition for enlightenment. "Could the reed-flute sing if its stomach were filled?"- Rumi

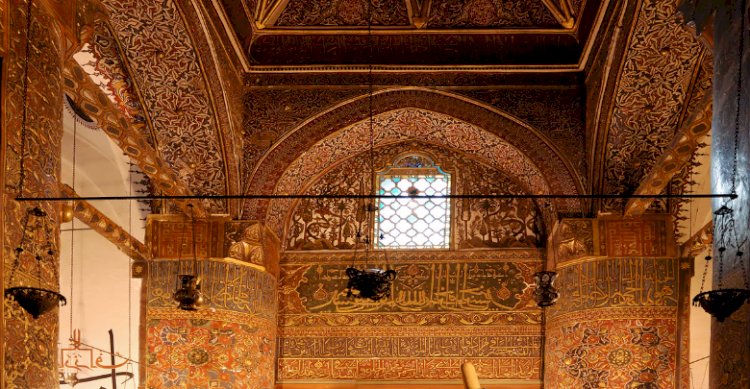

In general terms, alchemy (al-kīmiyāʾ) means the transmutation of base metals into precious ones such as lead into gold and silver, a mere philosophy transmitted from Greece to the Arab world during the ninth century. However, in the Muslim world, it paved the way for experimental sciences and the establishment of laboratories. Alchemists' attempt might have influenced the Sufis, the 'scientists of spiritual transmutation' as the latter borrowed this term to convince their analogy of spirit with metals. Therefore, Ibn al-ʿArabī indicated alchemy as a natural, spiritual, divine science.[1] In the Sufi sense, it was a natural philosophy that aimed not only at teaching the transmutation of the metals but also at the whole connection of the world.

Sufis consider hunger the best way to transform the human soul. They deeply ponder on Prophetic teachings such as " human does not fill any worse container than his stomach. It is sufficient for the son of Adam to eat what will support his back. If this is not possible, then one third for food, one third for drink, and one third for his breath."[2] The Quran states that fasting was obligated to transform humans into pious believers (Quran: 2: 183). Many similar scriptural statements urge them to find this correlation. One of the earliest Sufis to speak of the "alchemy of hunger" was Shaqiq al-Balkhī from Khurasan. He claimed that forty days of constant hunger could transform the darkness of heart into light.[3] He also maintained that "worship is a craft; its form is solitude, and its tools are hunger."[4]

There were attempts by Sufi theoreticians to elaborate on how hunger transforms the soul. For example, al-Hujwīrī explains: "Hearts are doors opened in their breasts, and at these doors are stationed reason and passion. The reason is reinforced by the spirit and passion by the lower soul. The more the natural humours are nourished by food, the stronger does, the lower soul become, and the more impetuously is passion diffused through the members of the body; and in every vein, a different kind of veil is produced. But when food is withheld from the lower soul, it grows weak, and the reason gains strength. The mysteries and evidence of God become more visible until the lower soul is unable to work. Passion is annihilated, every vain desire is effaced in the manifestation of the Truth, and the seeker of God attains to the whole of his desire."[5]

Hunger is a grace of God

Sufis considered hunger as a grace of God, and therefore they praised it too much. "It is stored up in treasure - houses with Him, and He gives it to none but whom He particularly loves."[6]

Medieval mystical poet, Jalal al-Dīn al-Rūmī beautifully described the grace of hunger in his Mathnawī.

"Until now, the (Divine) Bounty had not kept him without the daily provision, though at times He subjected his body to a (severe) hunger. Were hunger absent, in consequence of indigestion, a hundred other afflictions would raise their heads in you."

"Truly, the affliction of hunger is better than those maladies in respect both of its subtilty and its lightness and (its effect on devotional) work. The affliction of hunger is purer than (all other) afflictions, especially (as) in hunger there are a hundred advantages and excellences."

"Indeed, hunger is the king of medicines: hark, lay hunger to thy heart, do not regard it with such contempt. Everything unsweet is made sweet by hunger: without hunger all sweet things are unacceptable."[7]

"Hunger, in Truth, is not conquered by everyone, for this (world) is a place where fodder is abundant beyond measure. Hunger is bestowed as a gift on God's elect (alone), that through hunger, they may become puissant lions. How should hunger be bestowed on every beggarly churl? Since the fodder is not scarce, they set it before him."[8]

Mawlānā Rūmī further adds that just as the host brings better food when the guest eats little, God brings better, i.e., spiritual, food to those who fast.[9]

Excessive Fasting

Taking this matter into serious attention, some Sufis practised excessive fasting every day, which is known as ṣawm al-dahr, except on the prohibited days i.e., two Eids, and three days of Tashrīq. According to them, the hadiths which prohibit such constant fasting is about those who are not capable enough. However, others preferred ṣawm dāwūdi, which meant they would eat one day and fast one day so that their bodies would not become accustomed to either of the two states. They consider sawm dāwūdī more difficult for the human body than ṣawm al-dahr.

Moreover, some of them wished to depart this world in the state of fasting. This strong wish sometimes induced them to throw away the wet piece of cotton put in his mouth by his friends to relieve him during agony.[10]

Benefits of Hunger

Al-Ghazālī's seminal work, Iḥyā ʿUlūm al-Dīn, has synthesized ten benefits of hunger beginning with the most important one, purification of the heart and awakening intuition, followed by the delight of contemplation. He concludes that each benefit derives countless other benefits with endless rewards. However, he reminds that a novice should not suddenly reduce the food since it will intensify his suffering. Instead, try step by steps, thanks to him, for a very detailed practical guide of feeling hunger, especially for a beginner.

The above scholarly conceptions distract our hungry minds for comforts and luxuries, believing that they will strengthen us physically and mentally. However, divine law works in a different way. All kinds of afflictions are given to nourish human and make him courageous on the path, and that spiritual insight will make us calm and progressive in every moment. Getting used to hunger is the easiest way to face life's challenges and advance on the spiritual path at the same time.

[1] Ibn ʿArabī, Muḥyī al-Dīn, Al-futūḥāt al-Makkiyyah. Cairo,1329, vol. 2, p. 357.

[2] Jamiʿ al-Tirmidhī, Kitāb al-Zuhd

[3] See Paul Nwyia, S. J. Exegèse Coranique et Langage Mystique. Beirut, 1970. P. 216

[4] Abu Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Iḥyā ʿUlūm al-Dīn, (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifah, n.d.) vol. 3, p. 84 f.

[5] ʿAlī ibn Uthmān al-Hujwiri, Kashf al-Mahjub. Translate d b y Reynold A . Nicholson., Zia-ul-Qur’an: Lahore, 2000. p.424-425

[6] Abu Nasr al-Sarrāj, Kitāb al-Lumaʿ fī Taṣawwuf. Edited by Reynold A. Nicholson. Gibb Memorial Series, no. 22. Leiden and London, 1914. p. 202.

[7] Jalal al-Dīn al- Rūmī. Mathnawi-i Manawī . Edited and translated by Reynold A . Nicholson. London, 1925-40. Volume 5. Lines. 2828-32.

[8] Ibid., Lines 2837-38

[9] Ibid., Lines 1756

[10] See one such story in Mawlana Abd al-Rahman al-Jāmī. Nafaḥāt al-Uns. Edited by M. Tauhidipur. Tehran, 1957. P. 245.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment