Language Forming Identical Traditions within Religion: The Jawi and Arabi-Malayalam Stories

The reason for me to start learning the basics of Jawi was that I found something special in the Malay language (Bahasa Melayu) generally and Jawi in particular, which overtook what I observed in other Malay identities. The historical contexts of a language motivate us to contemplate how traditions, cultures, and civilizations are formed at various contexts through vernaculars, being some of them are too identical while some others otherwise. It is always astonishing for a learner to have experienced the similarities and dissimilarities between different communities and their traditions, while to some extent, we feel déjà vu when we engage with various Diasporas and phenomenologically grasp their identity. Here is a reflection of my primary encounter and experience with Jawi, recalling my Madrasah days 25 years ago, where I learned religion through the Arabi-Malayalam medium.

The Jawi Tradition

Jawi is an orthography, resembling Arabic with some additional characters, which is used for writing several Southeast Asian languages, including Malay, Acehnese, Banjarese, Minangkabau, Tausug etc. It is officially used in Brunei, whereas in the context of Malaysia, it was used as a regular script till 1972, before the standardization of Bahasa Melayu with Latin letters by the European colonial influence, especially the Dutch. Jawi is an adjective form derived from the Arabic noun jawah, both of which might have originated from ‘Jawadwipa’, the ancient name for Java. It is also thought that ‘Jawa’ and ‘Jawi’ may have been used by the Arab traders to indicate the whole Southeast Asian people.[1]

Like many other languages, Bahasa Melayu or Malay language also bears the stories of transition and transformation through ages. Bahasa Melayu is categorized into four periods: old Malay, early modern Malay, late modern Malay, and contemporary Malay. The first period, old Malay, refers to an era from 682 to 1500 C.E. in which the language was known as ‘Bahasa Melayu Kuno’. In this period, the Jawi script was used widely in Malay writings, together with Sanskrit. Then, in the early modern Malay period, starting from 1500 until 1850 C.E., some significant changes happened in the Malay language. The first among them was, during this period, the Melaka sultanate embraced Islam causing the spread of the religion across the whole Malay Archipelago. In par with this spread, the conversion of language was also taking place in the land through the infusion of Arabic, Persian, and Hindi into Malay. Following this, the Arabic rhetoric style was introduced to Bahasa Melayu, leading to certain changes in Malay grammar based on oral speech.[2] The seventeenth century witnessed the emergence of the great Romances, otherwise known as Hikayat, as the Malays started recording their experiences in Jawi script. The Hikayat is categorized as ‘Bahasa Melayu Klasik’ by Sir Richard O. Winstedt.[3] One of such Hikayat I read about recently was ‘The Trials of Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawīyya in the Malay World: The Female Sufi in the Hikayat Rabiʿah’, a monograph by Muaika Hijjas.[4]

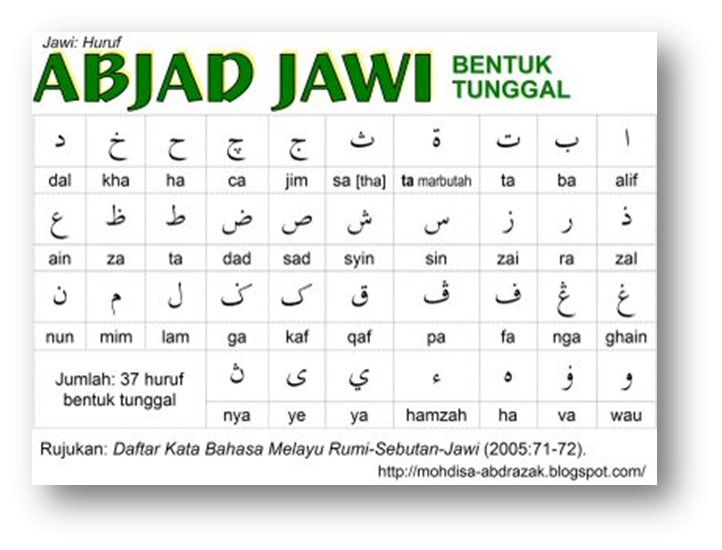

During the early stages of an Islamic renaissance in the country, the newcomers to Islam were taught to read and write in Arabic, recite Qur’an, and perform obligatory prayers. This led Malay people to accept Arabic alphabets for writing and speaking. In a sense, as they embraced Islam, their worldview was also converted extensively into Islamic. Gradually, they began to modify Bahasa Melayu by suiting it with Arabic. Thus, a new script was born, which resembled Arabic as written from right to left. However, unlike Arabic, there are six widely used sounds in Jawi, which are: ca (چ), pa (ڤ), nga (ڠ), nya (ڽ), ga (ݢ), and va (ۏ) (Figure 1), whereas many of the Arabic characters are not found in Jawi. Interestingly, the nature of the development of this Arab-Malay script is similar to that of Arabi-Malayalam, a South Indian vernacular. A comparison of both Jawi and Arab-Malayalam scripts is made later in this write-up.

Figure 1: Jawi Alphabets

Before Jawi was widely used, Malays used to depend on the Pallava script, of which the origin is thought to be from India. However, Pallava was restricted to a specific category of people. And when Malays embraced Islam, they realized that Pallava is no more helpful and appropriate for developing their Islamic worldview, whereby Jawi would fulfil this. As a result, this script started to be widely used in the Sultanates of Melaka, Johor, Brunei, Sulu, Pattani, and the Sultanates of Aceh to Ternate in the east as early as in 15th century. The Melakan merchants, poets, and clerks at royal durbars used this script widely as their only means to communicate. The main difference between the usage of Pallava and Jawi was that the former was used by only limited people, the elites, while the latter was an orthography of common people in the country.[5]

An Orthographic Comparison of Jawi and Arabi-Malayalam

The historical contexts for the development of Jawi (Arab-Malay) and Arabi-Malayalam scripts are fascinating by many dimensions. Islam was introduced to Malabar, which is Kerala, by Arab traders. Once they arrived at the coastal areas of the region, some of them never went back. Instead, they settled down in Malabar and turned influential in spreading Islam across the land. Similar to what happened to the early Malay Muslims, an Arabic-blended local language, i.e., Arabi-Malayalam, helped people learn Islam and assimilate it to their context.

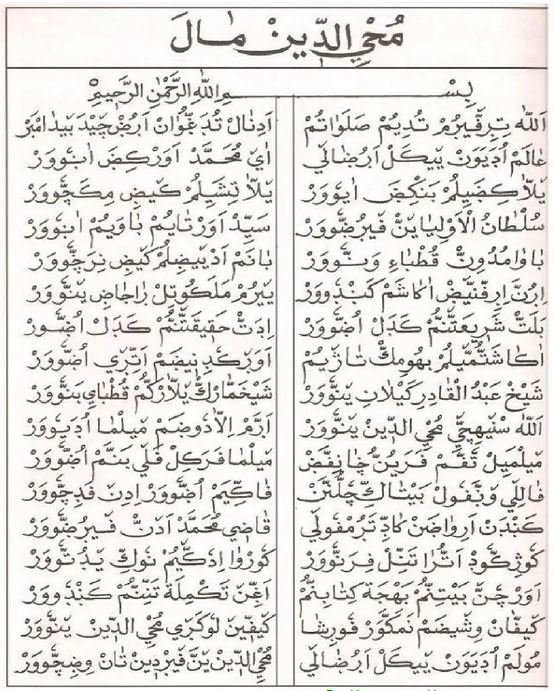

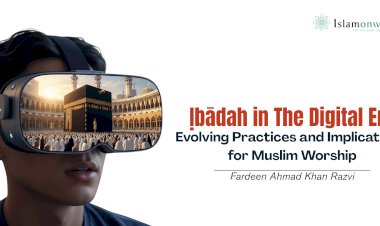

Like Jawi, Arabi-Malayalam uses different variations from Arabic characters. Its vocabulary is mainly from Arabic, Malayalam, Urdu, Tamil, and Persian. This script is still commonplace in most South Indian primary Madrasas, where the instructional materials are prepared in both Arabic and Arabi-Malayalam. Until the 20th century, Arabi-Malayalam was taught for every Keralite Muslim. Same as the Malay-Jawi, Arabi-Malayalam is also rich with several literary works, including long poems. The earliest of such works is Muhyuddin Mala, a traditional heroic poem about ʾAbd al-Qadir al-Jīlani of Baghdad, written in 1607. Almost 3000 Arabic words, which were also used in Arabi-Malayalam, were later assimilated to the Malayalam language, showing the significant influence of a blended lingua franca on the Malayali (one who speaks Malayalam) life.

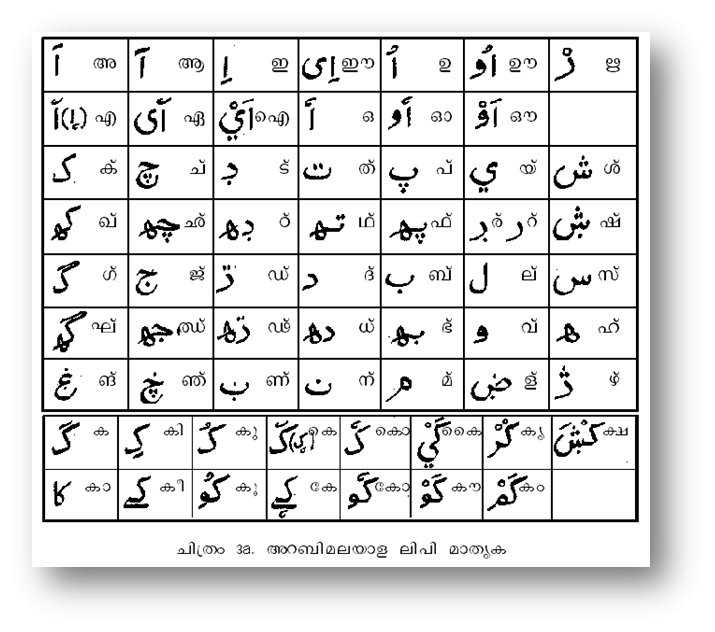

As mentioned earlier, characters that are unavailable in Arabic were developed in Jawi for mass convenience. As for Arabi-Malayalam, it includes several additional sounds such as cha (چ), pa (پ), nga (ۼ), nja (ڿ), ta (ڊ), and zha (ژ), borrowed from Malayalam (Figure 2). However, as an explicit difference between the both, no diacritic (harakah) is used in Jawi, whereby the case is otherwise in Arabi-Malayalam. So, for differentiating ‘/a/’ from ‘/u/’, for example, in Jawi, they use ‘alif’ (ا) and ‘waw’ (و) respectively, while just two harakahs (َ and ُ) do it in the latter.

Figure 2: Arabi-Malayalam Alphabets

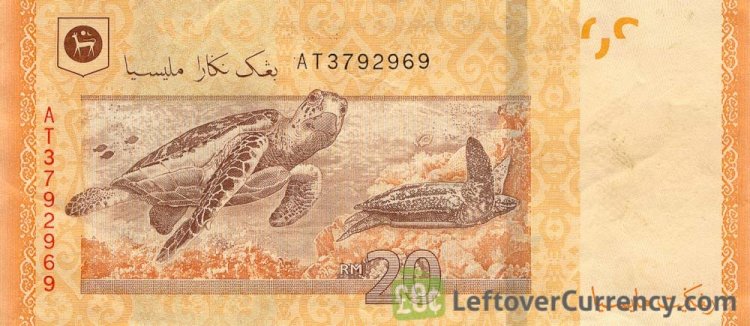

Interestingly, Jawi is still being used, though limitedly, as a religious and cultural lingua franca in Malaysia, especially in Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah, Perlis, and Johor. This orthography bears an official status on the Malaysian currency (Ringgit), as both the Bank and currency names are written in Jawi (Figure 3). Similarly, Pattanis of Thailand also use it at a minimal level, such as labeling their coins and currencies. It is also common in the Malay-dominant regions of Indonesia, including Riau, Ache etc., since their primary religious education curriculum requires learning the Jawi script. Moreover, some of their textbooks are prepared using the same, as seen in Javan traditional religious schools, despite the dominion of Latin alphabets in several other parts of the country. This is similar to the current scenario in South Indian Arabi-Malayalam vernacular, as more than ten thousand Madrasas in Kerala engage with this script through their textbooks. However, unlike Jawi, no official status has been given to this orthography, except that it is recognized as an ethnoreligious symbol of Keralite Muslims.

Figure 3: Malaysian Currencies (Ringgit Malaysia) with Jawi orthography

Survival: between Entanglement and Engagement

The fact that Jawi has faced dismal negligence from those who were supposed to preserve it cannot be denied, though. As the Malay-Indonesian Diaspora reached its pinnacle of expansion, Jawi had also enjoyed its prevalence throughout its early Islamization periods. Then, however, a drastic decline happened to this script due to the invasion of Rumi, the Latin script introduced by Portuguese and British colonialism. Hence, from the nineteenth century onwards, Jawi was no longer promoted in the country.

While the present Jawi promoters grieve that the Malay youth are to be blamed for the decay of a script that marked some legacies in South-East Asian history, voices for Jawi are still heard from different regions. As Professor Dr Kang Kyoung Seok, a Korean expert in Jawi script, opines, the promotion and preservation of Jawi lie in the hands of Malay youngsters, not anyone else.[6] He warns that if they fail in doing so, it will be a painful end. He concluded as such, realizing that although there are many foreigners interested in Jawi, they are limited to academia. Nevertheless, instead of putting all the responsibilities on and blaming the youth, there should be prompt and effective strategies to reclaim the tradition of Jawi.

In a recent response to the issues related to Jawi, Datuk Razali Ibrahim expressed the same concern, urging students to use it throughout their study in the hope that it would help keep the Malay Muslim identity, especially in literary aspects. ‘Jawi script needs to be revived by including it as an instrument or digital application in an effort to elevate the writing. An application should be created, for example, to find out the words of the writing.’[7]

Dr Tan Seng Giaw, the veteran DAP leader, who has already mastered Jawi right after his graduation from England in 1970, empathizes with Jawi and its present condition as he asserts that if Malays want to pass their culture to their generations, they are in urgent need of teaching their children the unique Jawi script in which all the Malay identities are preserved. ‘Whatever it is, one has to learn Jawi language, otherwise, how will you know the Malays?’ He asks the Malays.[8]

Figure 4: Muhyuddin Mala, a traditional heroic poem about ʾAbd al-Qadir al-Jīlani of Baghdad

The exact dilemma is faced by Arabi-Malayalam since there have been some internal debates on whether this language should be kept in Madrasas, while the modernists continue to be the ardent criticizers of such practices. That is why they have already removed this cultural mark from their textbooks, replacing it with a modern Malayalam. On the contrary, the traditionalists- i.e., the majority- are actively interacting with it in many ways, such as conducting Arabi Malayalam literary discussions[9], performing arts etc. In other words, the latter’s reluctance to change and adapt the modernist discourses has substantially contributed to preserving Arabi-Malayalam, though there has not been any explicit consensus on the mentioned point.

To conclude, both Jawi and Arabi-Malayalam are evidently the end result of an identical phenomenon, which is the ethnolinguistic assimilations through a framework of Islam. Both will remain as long as their religion is there but will continue to face the crises of an identity entanglement in different ways. Thus, to be extinct in the near future is far from possible for both languages, while their ineffective survival could be predicted in all spheres. Like scholars, the laymen should cognize that the survival of these two languages will cherish their past to the extent that it will help them engage with the present by making conversation with the past.

(Dr Jafar Paramboor is currently working as an Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Foundation and Educational Leadership, IIUM Kuala Lumpur Campus. He is one of the editorial board members of Islamonweb English, and has authored on education, teaching, and learning, from Islamic perspective. He can be reached at: pjafar@iium.edu.my)

[1] Jawi alphabet. (2022). In Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jawi_alphabet&oldid=1073225464

[2] https://ling-app.medium.com/history-of-malay-language-the-3-revolutionary-phases-7f805efc52a6

[3] Reid, A. (2001). Understanding melayu (Malay) as a source of diverse modern identities. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 32(3), 295–313. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20072348

[4] Hijjas, M. (2018). The Trials of Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawīyya in the Malay World: The Female Sufi in the Hikayat Rabiʿah. Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 174(2–3), 216–243. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-17402025

[5] Badd. (2019, August 19). The history of the Malay language, from Pallava to Jawi to modern Malay, simplified. https://cilisos.my/the-history-of-the-malay-language-from-pallava-to-jawi-to-modern-malay-simplified/

[6] Pressreader.com—digital newspaper & magazine subscriptions. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2022, from https://www.pressreader.com/malaysia/the-borneo-post-sabah/20160607/281870117703655

[7] Jawi script needs new breath of fresh air. (2016). www.thesundaily.my. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from https://www.thesundaily.my/archive/1389029-BSARCH305521

[8] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2019/08/09/jawi-easier-to-learn-than-mandarin-says-dap-veteran/

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment