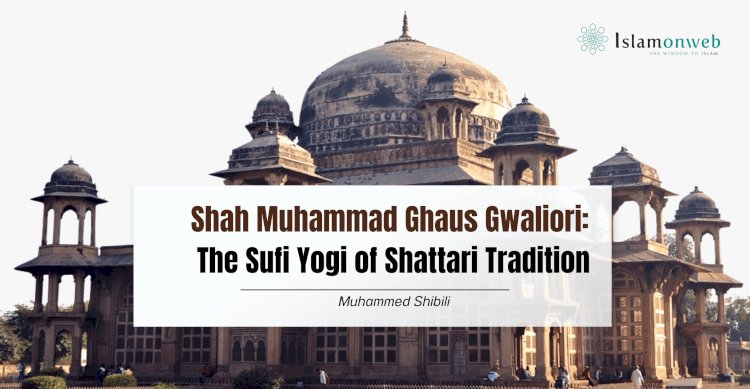

Shah Muhammad Ghaus Gwaliori: The Sufi Yogi of Shattari Tradition

Shah Muhammad Ghaus Gwaliori was one of the most influential figures in the Shattari Sufi tradition—a 16th-century scholar and mystic who played a pivotal role in embedding this spiritual path into the cultural and religious fabric of India. Despite his profound contributions, his legacy remains underappreciated in the broader narratives of Indian history.

Gwaliori was not merely a spiritual guide; he was also a poet, philosopher, and musician. His unconventional approach and deep mystical practices often brought him into conflict with orthodox religious authorities, earning him the title of Sufi Yogi—a term that unsettled many conservative scholars of his time.

His spiritual lineage traces back to the legendary Persian Sufi and poet Khwāja Farīduddīn ʿAṭṭār of Nishapur and extends to Ḥājī Ḥamīd Ḥaẓūr of Gopalganj, Bihar—both towering figures in the history of Islamic mysticism.

The word Shattār originates from Persian, with roots in Arabic, and carries meanings such as “lightning” and “radiance.” Beyond its literal sense, it symbolises the essence of the Shattari path—a mystical journey guiding seekers toward divine light (Nūr). Although the tradition began in Persia, it reached its fullest expression in India, a land enriched by the presence of countless enlightened saints. Over time, the Shattari order evolved into a significant spiritual movement, intertwining with the Ṭayfūrī khanwāda and eventually gaining recognition under the name Shattari-Qadiri.

Shah Muhammad Ghaus was also deeply influenced by Ghawth al-Aʿẓam Shaykh ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī (RA), through whose spiritual inspiration he ascended the ranks of the Qadiri order. Journeying from Nishapur to India, he devoted his life to guiding people toward divine love and the gentle path of Sufism.

His contributions extended well beyond the popularisation of the Shattari order; he was instrumental in formalising it into a structured and enduring spiritual tradition within India. His legacy shaped not only the theological and mystical discourse but also left a lasting imprint on Indian Muslim thought, culture, literature, and art for generations.

As a philosopher and writer, Shah Muhammad Ghaus Gwaliori immersed himself in the study of ancient Indian yogic texts, bridging Indic spiritual traditions with Islamic mysticism. His seminal works—Jawāhir-e-Khamsa (The Five Jewels) and Baḥr al-Ḥayāt (The Ocean of Life)—reflect a profound synthesis of Sufi thought and yogic philosophy. Notably, he was among the first scholars in the 16th century to translate yogic scriptures into Persian, making their intricate teachings accessible to a broader audience.

While earlier mystics such as Shaykh ʿAbd al-Quddūs Gangohī—a 13th-century Sufi poet—had explored Nāth yogic practices associated with Shaivism, it was Gwaliori who undertook a systematic translation and exposition of these texts. Despite resistance from orthodox religious scholars, he pursued this endeavour with unwavering resolve. His translations laid the groundwork for subsequent renderings into Arabic, Turkish, Urdu, and other languages, extending the reach of yogic wisdom well beyond the Indian subcontinent.

His most celebrated translation, Baḥr al-Ḥayāt, completed in 1550 in Broach (modern-day Bharuch), Gujarat, was based on the Amṛtakunda—a key Sanskrit text on yoga. It was soon translated into Arabic under the title Ḥawḍ al-Ḥayāt (The Pool of Life), becoming a cornerstone of Shattari teachings. Another important contribution, Jawāhir-e-Khamsa, delved into the profound affinities between Sufi practices and yogic disciplines. This work was later translated into Arabic by Sibghatullāh, a Shattari scholar from Mecca. In it, Gwaliori documented his mystical experiences—so intense and transformative that he claimed they enabled direct communion with the Divine.

Gwalior and the Legacy of Muhammad Ghaus Shattari

Gwalior, located in Madhya Pradesh, has long stood as a centre of cultural and historical prominence. The city bears the enduring imprints of emperors, kings, and queens, all of whom contributed to its illustrious past. Yet beyond its regal legacy, Gwalior has also been a revered spiritual hub, home to saints and sages who enriched its religious and mystical heritage. The city’s name is believed to derive from the legendary hermit-saint Gwalipa. Among the spiritual figures associated with Gwalior, Shah Muhammad Ghaus Shattari emerges as one of the most influential, leaving a profound impact on Sufism and Indian cultural life.

Muhammad Ghaus held a distinguished position in the eyes of three Mughal emperors: Bābur, Humāyūn, and Akbar. He played a crucial role in Bābur’s conquest of the Gwalior Fort in 1526, advising Mughal commanders with strategic counsel, including confidential intelligence that facilitated a successful night assault. His relationship with Humāyūn was equally significant, serving as the emperor’s spiritual mentor and guide in occult sciences. However, during the political upheaval of 1540, when Humāyūn was overthrown by Sher Shah Suri, Ghaus sought refuge in Gujarat to avoid persecution by the Afghan forces. He later returned to Gwalior once the Mughal empire was restored under Akbar. Following his death in 1563, a grand mausoleum was erected in his honour—a monument that stands to this day as a testament to his enduring legacy.

Muhammad Ghaus’s influence extended well beyond the spheres of politics and spirituality. He was closely connected to the arts, particularly music. After assisting Bābur in his military campaign, Ghaus established a khānqāh (hospice) in Gwalior, which evolved into a centre of artistic and creative expression. Among those who benefited from his patronage was the legendary musician Tansen. Originally trained by Swami Haridās, Tansen later came under the influence of Muhammad Ghaus, who infused his musical practice with a deep Sufi spirit. Today, the tombs of Tansen and his mentor stand side by side as a symbol of the fusion of spiritual and artistic traditions nurtured in Gwalior.

Muhammad Ghaus’ tomb, built in 1563 during Akbar’s reign, stands as a fine specimen of early Mughal architecture. The structure is square-shaped with a large central dome, which was originally adorned with blue glazed tiles. While the tiles have faded over time, the mausoleum remains a masterpiece, showcasing an Indo-Muslim architectural style influenced by elements from Gujarat and Rajasthan. One of its most striking features is the intricate jali (perforated stone screens), which adorn the exterior walls. These screens, designed with geometric patterns, create a serene atmosphere by allowing filtered light and air into the tomb chamber.

As with other Sufi shrines, the area surrounding Muhammad Ghaus' tomb is considered sacred, and several unnamed graves can be found around the site. He was also the spiritual guide to Shahul Hameed Naguri, a revered Sufi from South India. His contributions to the Shattari order, adaptation of yogic practices, and promotion of secular values continue to be remembered, ensuring his spiritual legacy lives on.

Sufis have always had a way of blending into the lands they journeyed to, becoming an inseparable part of the culture rather than remaining outsiders. People, regardless of faith, were drawn to them—not because of miracles or grand displays, but because of the depth of their spiritual presence. Through them, countless individuals found their way onto the Ilāhī Sabīl (Divine Path). Even after their passing, the love and devotion of their followers never faded, and their shrines remain sacred places of pilgrimage.

Just like Khwāja Gharīb Nawāz, Māmburam Thangal, and Ibrāhīm Bādushā, Shah Muhammad Ghaus Gwaliori holds a timeless place in India’s spiritual heritage. Sufi mystics like him and Shaykh ʿAbd al-Quddūs Gangohī played a crucial role in embracing and interpreting India’s spiritual traditions, even in the face of resistance from orthodox scholars. Their tireless efforts bridged cultural divides, bringing the wisdom of yoga and Sufism to the world—ensuring that their influence continues to shine across centuries.

About the author:

Muhammed Shibili is a Sociology student at Pondicherry University and also pursues Theology and Philosophy at Darul Huda Islamic University. Fluent in six languages, he is an accomplished author, Chief Editor of Baliperunnal, and actively engaged in cultural and religious activities. As a campus leader, he has served as Chairman of Malayalikkoottam. His academic dedication and versatile involvement reflect a well-rounded personality.

References:

- Gwaliori, Shah Muhammad Ghaus. Bahr al-Hayat (The Ocean of Life). 1602. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahr_al-Hayat.

- Gwaliori, Shah Muhammad Ghaus. Jawahir-e-Khamsa (The Five Jewels). Translated by Sibgatullah. Mecca. 2025. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.375481.

- "Life and the Religious Thought of Shaikh Muhammad Ghawth of Shattari Silsilah." ResearchGate. . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359525243_Life_and_the_religious_thought_of_Shaikh_Muhammad_Ghawth_of_Shattari_Silsilah.

- "The Shaykh and the Shah: On the Five Jewels of Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliori." Academia.edu. .https://www.academia.edu/35837676/The_Shaykh_and_the_Shah_On_the_Five_Jewels_of_Muhammad_Ghaws_Gwaliori.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment