Other Relevant Sub-Maxims in the Elimination of Harm - Part five

By Dr. Sayyed Mohamed Muhsin, Dr. Muhammad Amanullah and Dr. Luqman Zakariyah

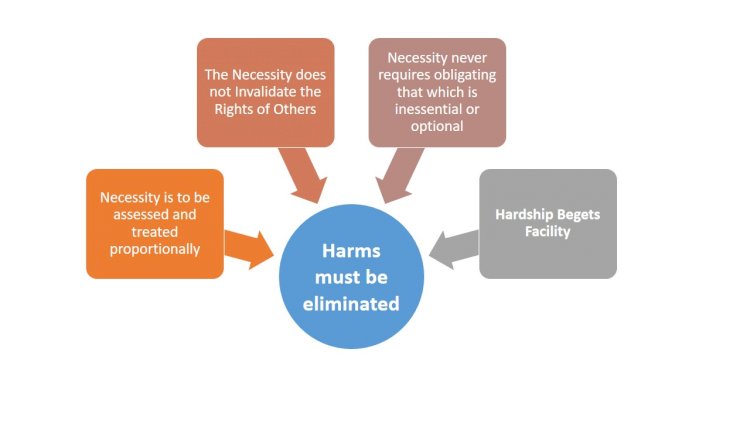

Some other sub-maxims function as either regulators or conditions for the application of the harm elimination maxims in appropriate ways. They are as follows:

The Necessity does not Invalidate the Rights of Others

This maxim (al-iḍṭirār lā yubṭilu ḥaqq al-ghayr[1]) expounds that commission of prohibited and avoidance of required due to the necessity are allowed with a condition that it should not be harmful to others. For the preservation of the essentials, Islamic law allows prohibited things to be committed but only to replace the state of necessity. However, necessity does not invalidate the rights of others, though it tolerates breaching certain rulings but with owing a liability to the harmed. For example, in order to overcome hardship, the Sharīʿah allows using others’ property but with liability to return the thing similar to it or its price, otherwise it may culminate to harming the owner while “harm is not removed with harm”. Logically, if there is no liability it turns to be harmful to the owner of the property.

Hardship Begets Facility

Hardship (mashaqqah) means an unusual difficulty. The usual hardships are inescapable in many meritorious actions and even in unavoidable daily routines we exercise; they however do not pose any reasonable risk to people. These minimal hardships are excluded from the scope of this maxim. Rather, the hardship in question surrounds the kind that poses threat to the life or that is capable of inflicting permanent disability and the like. In situations of significant hardship, the Sharīʿah facilitates a person with easier alternatives that are operated either by omission of the obligatory or commission of the forbidden deed.

The maxim hardship begets facility (al-mashaqqatu tajlib al-taysīr[2]) forms in and of itself one among the five universal maxims; however, some scholars include it in the subsidiaries of harm maxim. The difference between harm maxim and hardship maxim is that the former is applied when its elimination or prevention is feasible while the latter is used by begetting facility to remove obstacles and to ease the burden of lives. The application of hardship maxim is restricted by another maxim "whatever is permissible owing to some excuse ceases to be permissible with the disappearance of that excuse." It means that facilitation is valid only in the presence of impediment, and once it is removed, the original ruling is restored to full effect.

The maxim “necessity is to be assessed and treated proportionally” (al-ḍarūrat tuqaddaru bi qadrihā)[3] is considered as a constraint to the hardship maxim. This maxim strictly stipulates that any permitted thing in the face of extreme necessity should not go beyond the parameters of necessity. This maxim is supplemented by the maxim “necessities render the prohibited permissible”.[4] The maxim of necessity has been legislated in order to eliminate the harms during a necessity and to save the ummah from its predicaments.

CONCLUSION

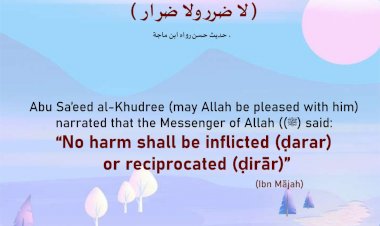

The maxim regarding the elimination of harm is construed as prohibition of all actions and inactions that carry the notions of wronging, infringing on other’s rights, frustrating, overpowering, or setting back some party’s interests. The prohibition on the infliction of harms extends to harming oneself, harming others and becoming causative of harms. The maxim of harm elimination is deemed as a key principle employed for the legal derivation especially dealing with social ethics and interpersonal relationships in Islam. Likewise, it is among main reference for deducing the legal rulings on modern issues. The scope of this maxim in terms of its applications is very broad and is relevant to almost all areas of fiqh.

This principle is not absolute rather it is accompanied by limits, as if a harm is inflicted to prevent bigger harm, it is treated as justifiable. Thus, there are situations in which harms are taken as justified or compromised considering their consequences if they are on balance, as in the case of punishment of legitimate retaliation or legal demotion of an employee for a valid reason or disciplinary action.

The aspect of prevention is given preference as it thwarts ramification of the harm and governs in line with the widely recognized principle ‘prevention is better than cure’. However, the prevention of harms is not always feasible because of the inherent differences in the priorities of human beings, which inevitably results in the infliction of harms on others, intentionally or unintentionally, directly or indirectly.

In these circumstances, the elimination of the harm after its occurrence becomes obligatory to mitigate the difficulties and to prevent its future occurrence. Likewise, the complete elimination of harms is not at all times in the capacity of human beings. Addressing this issue, the third aspect guides to minimize the adverse effects of the harm to the people and the system as much as possible.

In the light of the previous detailed discussion, a flowchart that represents a sequence of five steps is derived, which are beneficial to be taken into consideration in the course of harm elimination. The details are as follows:

Step 1: Ascertain that the consequence of his decision averts considerable harm. An action or inaction is regarded as considerable harm if it meets the following conditions:

- Harm is real

- Harm is serious

- Harm is inflicted in an illegitimate way

- Harm is inflicted on a valid benefit

Step 2: Make the arrangements of harm elimination according to the agreeable hierarchy, which is as follows:

Prevention Elimination Minimization

Step 3: Three governing principles must be in the hearts of agents when they apply the maxims of prevention of harm before its occurrence, they are:

- “No harm shall be inflicted or reciprocated”. The health worker should be neither initiating any harm nor reciprocating with any harm.

- ‘Harm should be avoided as much as possible. It means that a healthcare professional exerts his possible efforts to prevent as much harm as possible.

- Repelling harm is preferred to the achievement of benefits

Step 4: Eliminate if the harm has already happened as per the maxim “harm must be eliminated”. One of governing principles in this stage is “harms should not be replaced with another harm”. As a result, removal of harms without leaving any other harm and leaving lesser harms are only accepted. Likewise, the maxim “lapse of time cannot justify the continuation of harm” emphasizes that the materials and reasons for harm, which have existed for a long time, are to be removed and there is no regard for their long duration of existence.

Also read: sub maxims related to the prevention of harm before occurrence - part two

Step 4: Minimize the harms if they are unavoidable. Two governing principles are noteworthy in this stage; they are:

- The greater harm should be prevented by committing the lesser harm.

- Personal injury should be incurred to prevent general injury.

Step 5: Make a decision that is harm-free or with the least possible harm in unavoidable situations. For the most appropriate and valid harm elimination procedures, the professionals should keep in mind the below maxims also:

- Committing that which is prohibited is not allowed except in the case of dire necessity.

- Necessity never requires obligating that which is inessential or optional.

- The necessity does not invalidate the rights of others.

- Hardship begets facility.

(This article is part of a research work which was originally published on Islamic Quarterly, UK December 2019).

Reference

[1] al-Zarqā, al-Madkhal al-Fiqhī, 602; al-Khādimī, Manāfiʿ al-Daqā’iq, 331; Majallat al-Aḥkām, 33; Ibn Rajab, Qawāʿid, 26.

[2] Al-Suyūṭī, al-Ashbāh wa al-Naẓā’ir, 76; Ibn Nujaym, al-AshbÉh wa al-NaÐÉ’ir, 74; al-Zarqā, al-Madkhal al-Fiqhī, 598; Majallat al-Aḥkām, 17.

[3] Al-Suyūṭī, al-Ashbāh wal-Naẓā’ir, 84; Ibn Nujaym, al-Ashbāh wal-Naẓā’ir, 78; Muḥammad al-Zuḥaylī, al-Qawāʿid al-Fiqhiyyah, 1: 226.

[4] Ibn Nujaym, al-AshbÉh wa al-NaÐÉ’ir, 85.

(Sayyed Mohamed Muhsin is Assistant Professor at Department of Fiqh and Usul al-Fiqh, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur; Dr. Muhammad Amanullah is Professor at Department of Fiqh and Uṣūl al-Fiqh, International Islamic University Malaysia; Dr. Luqman Zakariyah is Professor at Islamic Studies Unit, University of Kashere, Nigeria)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment