Lived Islam in Kashmir: Engagements of Kashmiri Muslims with Local Culture - Part I

Part I

The Kashmir division of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmiris the most prominent Muslim majority region in India, with not less than 94 per cent of the Muslim population recorded in the earliest census of the region. Among them, only around 5 per cent belong to the Shia sect, and all of the rest are Sunni Muslims. Kashmiri Pandits, the only Hindus of Kashmir, constituted around 4 to 5 per cent of the population, before they migrated from the valley during the 1950s and 1990s. The predominant majority of Kashmiri Muslims are converted from Hinduism and a few more from Buddhism. In the 14th century, we see Islam was introduced in Kashmir and popularised in the subsequent centuries by Sufi sheikhs of Persia and other Central Asian regions and by the local mystics of Kashmir known as Rishis. At the turn of the 16th century, we see Islam replaced Hinduism as the mass religion of Kashmir.

The process of Islamization of Kashmir was a gradual one and is one of the best examples of the peaceful takeover of one religion and culture by the other and thus does not fall within the category of what is sometimes called ‘the Islamic expansion by the sword’ or ‘conversion under Muslim political rule, established by conquest’. Despite Kashmir’s mass transition to Islam, the history of Islam in the valley shows that the Muslims did not completely part their ways with the pre-Islamic practices for a pretty long period after the conversion. Mass conversion in Kashmir is considered as a ‘little more than shifting of camps’, and thus the actual conversion from the pre-Islamic way of life to that of the Islamic one is said to have remained far from achieved.

The formal or nominal conversion to Islam and practical adherence to the old culture thus went hand in hand. Islam in Kashmir, as it is argued by different observers, was adopted by the masses superficially, mainly its ritual side. This lax religious behaviour of the converts was observed even in earlier decades of the spread of Islam. Despite the lapse of fifty years since the establishment of the Muslim Sultanate in 1339 C.E., and the presence of Muslim preachers there was an open breach of Islamic teachings by the neo-converts and the life pattern of the Muslims including that of the ruling family that was not much different from that of the Hindus.

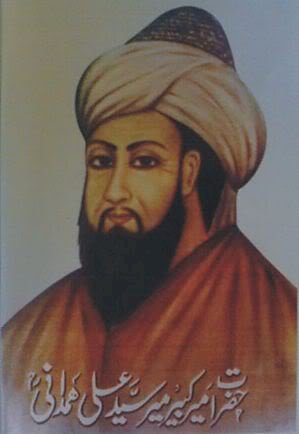

The Muslim community had virtually adopted a Hindu way of life, to the extent that they were even worshipping idols, celebrating the Hindu festivals, and dressing after the Hindu fashion until they were taught to give up this blatant breach of sharia and Islamic spirit by the famous Sufi sheikh.[i] of Persia Mir Sayyid ‘Ali Hamdani, popularly known in Kashmir by various reverential titles as Amir-i-Kabir (Great Leader), Shah-i-Hamdan (King of Hamdan), Bani-e-Islam (Founder of Islam), Bani-e-Mussalmani (founder of Muslims), who along with his 700 followers arrived in Kashmir in 1384 and began spreading the Islamic faith among common masses and introduced the Kubravi order of Sufism in Kashmir.

Although the Kubravi Sheikh strived enough to Islamize Kashmir, that did not help the converts to completely part their ways with the past and the mass conversion continues to remain purely nominal until very recently when only institutionalized Islam became stronger in every nook and corner of the valley. And thus it is being held that a real conversion to Islam remained a far-fetched dream, never realized at any stage of Kashmir history till our times; especially when we consider that Islam demands from its adherents a total transformation in which a prior religious identity, behaviour pattern and mentality are wholly rejected and replaced by a new one.

Some European observers of the 19th century were surprised to see the laxity that Kashmiri Muslims observed in the practice of their religion even after the passage of many centuries of their conversion. The 19th-century observer of Kashmiri society, Walter Lawrence, found dominant Kashmiri Muslims as, 'Hindus at heart', 'saint worshippers', 'pīr parast’ and lax in their religious duties.

The main point put forward by historians, sociologists, European observers and Muslim revivalists to support the contention that the Kashmiri Muslims have retained the elements of Hinduism is the dominant prevalence of what the critics normally describe as 'saint and shrine worship' among the Muslims of Kashmir and the religion of Islam was thought to be 'too abstract to satisfy their superstitious cravings'.

What Lawrence observed on Kashmiri Muslims' religious behaviour towards the close of the 19th century remains true even today in most Muslims there. Mass visits to the shrines is still a commonplace phenomenon among a large section of Muslims in the valley. The people believe that visiting the shrines and praying there would fulfil their worldly wishes as their graves are believed to be possessed of miraculous powers and listen to and help grant their devotees' wishes. They would pay nazar/niyaz (gift) to the shrine when they are granted their wishes. The supplicants also tie votive rags (d’ash) to the shrines for securing worldly objectives. The rag is left in its place till the objective gets realized. The devotees smear their face, throat and body with the dust in precincts of the shrine, gaze at it and seek blessings with folded hands.

Some of the shrines are also visited to settle the disputes between two parties over any issue where they take an oath with the belief that the liar would incur the wrath of the Sufi sheikh. The wrath of a dead Sufi sheikh in my nearby village is believed to be so furious that a liar is bound to be blinded for life if he/she takes a false oath of truthfulness. The shrine of the Sufi sheikh is still held in much veneration, and the people even turn off their music system in the vehicles when they pass by it.

They also celebrate the annual day (‘urs, locally known as warus) of Sufi sheikhs at their shrines where the devotees assemble in large numbers leading to annual fairs where men and women mingle freely, now from past decades becoming a too rare phenomenon. Besides, the people of different social groups of different localities would still celebrate the annual day of their respective saints (who generally belong to a local Rishi sect) and on that day only that particular vegetable is cooked which was preferred by their saint. The devotees would not eat any other vegetable or non-vegetarian food during the ‘urs, which normally remains for two to three days. However, owing to the spread of Islamic teachings, the psyche of recent generation Muslims has got transformed to a large extent with relation to these practices.

There also seems an influence of some elements of primitive Naga worship of Hindus on the Kashmiri Muslims. In Kashmiri Hindu mythology Nagas (serpents) are designated as the tutelary deities who reside in the springs and lakes of Kashmir. The popular conception of the Nagas represents them in the form of snakes, living in the water of the springs or lakes protected by them and can also appear in human shape. Hindus of the valley had built numerous temples near the most famous springs as these are believed by them to be the abodes of Nagas, and up to this day, annual pilgrimages by the Kashmiri Hindus are directed towards them.

The spring is called nag in Kashmiri because of the association of Naga worship with it and so much deep-rooted was the belief of springs being abodes of spirits with supernatural powers that people could not forget it despite their conversion to Islam. No Muslim would dare to spit around a nag believing that it will bring the displeasure of the spirit (tasrufdar) of the nag, nor would anyone pass by it along with a child especially on the Friday or during a night time else the child or even an adult would be possessed by the tasrufdar. In my entire life, I have never come across a single example that anyone in Kashmir has ever dared to eat or kill the fish of any spring. It is believed rather feared by the people that doing so would either lead them to death or make them dumb or blind. It is a common saying in Kashmiri that the fishes of springs are halal (allowed) to see but haram (forbidden) to eat.

In a nearby nag of Trehgam town in my locality, there are so many fishes of different colours (colourful fishes in Kashmir are peculiar to these springs only) which are held sacred by the people. Besides holding the aforementioned beliefs, people believe that there is a sort of head fish who has golden earrings and is visible on Fridays and to pious ones only. This all can be ascribed to the legacy of the deep-rooted Naga cult.

During times of drought or scarcity, people would even make offerings of goat, sheep or a bull, collectively arranged by the villagers, at the springs so that the power residing in the springs would be pleased to release the water for irrigating their dry fields. But this practice was confined to those areas where irrigation of the fields depended wholly upon these springs and not in the regions where fields are irrigated by the rivers where people would make an animal sacrifice to a local shrine (astan) during an imminent threat of flooding. However, for the past few decades, this practice is becoming too rare thanks to the efforts of the Islamic scholars for strengthening the Islamic institutions.

What is interesting to note is that both the early Sufis (who generally were great Islamic scholars) and the local Rishis believed in the supernaturalism of the springs by holding a view that the spirits occupying the springs could assume the form of human beings and snakes. However, they Islamized the belief by making the people believe that the majority of the spirits of the springs had been converted to Islam as many of the spirits visited them ‘to seek guidance’.

It would be pertinent to relate here an interesting thing about the belief in naga spirits which I myself witnessed around some four years ago. My friend’s wife (25 years old) was believed to be possessed by a spirit as she was having some mental delirium and after modern treatments failed, she was suggested to visit some pīr (a religious person). The friend requested me to accompany him to the pīr in a nearby village. The pīr was well versed in Islamic teachings and was a school teacher also. Just when the pīr put his hand on the forehead of my friend’s wife, she fell down unconscious for a moment. Once she regained her consciousness before us, she was not the same person as before. The pīr began to ask her questions, indirectly to the spirit, that why it is bothering the poor fellow. The ‘male spirit’ started replying that this woman had disturbed him at some nag and had caused some injury to his children. To my utter surprise, when the spirit was asked for his name, it came out to be a non-Muslim spirit with a Hindu name. To this, the pīr jokingly asked him that his fellow religionists had long ago left the valley in the 1990s. What was he still doing there?

Then there is another pre-Islamic belief—the sacredness of the trees—which still holds good weight on the psyche of Kashmiri Muslims. The tree spirits were worshipped by different primitive religious groups of the world, and Hindus of Kashmir were no exception. Along with the tombs of Sufi sheikhs, the big trees around them or at places regarded sacred for having some association with the Sufi sheikhs are still held sacred and no one would dare to cut them down or use the wood for domestic purposes. Just around my own house in Kashmir, two such trees are held sacred or feared by the people of our Mohallah (colony).

We, as children, were strictly prohibited from roaming around any one of the trees on Fridays and during evening time as our elders believed that the tasrufdars (spirits) are more active during these periods of time and we might be possessed by them. To appease these spirits, the families of our ward would on occasional Fridays take a specially cooked rice with milk in a traim (a big Kashmir plate in which four persons eat together on festive occasions) to any one of the trees which only the children were supposed to eat under the shade of the tree. Before taking our own morsel, we were strictly directed to throw another one on the ground for tasrufdar first, then for birds, and finally, we could eat. Such beliefs and practices are not peculiar just to our place; rather, these are the generalized practices of the whole Kashmir. However, such practices are becoming rare nowadays.

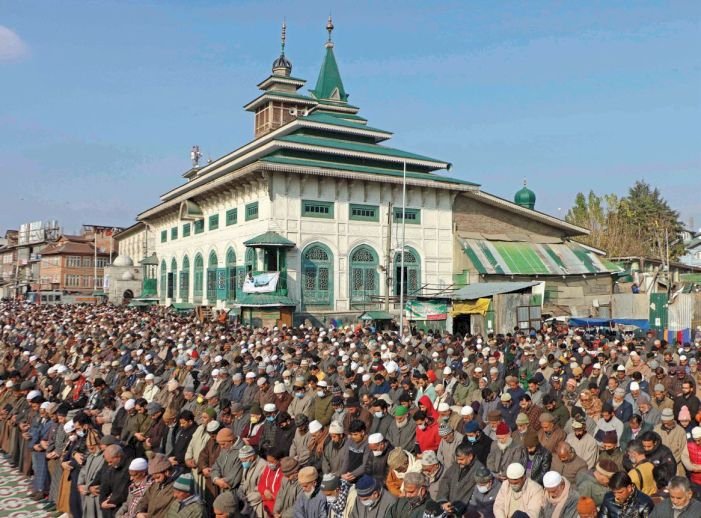

An exceptional feature of the mode of prayer of Kashmiri Muslims is the loud congregational recitation of Aurad-i-Fatthiyya (after morning prayers). It is said that the converts missed their temple worship of singing hymns aloud and beating of drums which had assumed such a venerated and devotional place in the religious scheme of the Hindus that for launching a successful conversion movement the Muslim missionaries were left with no alternative but to adjust it to the local religious ethos. So, Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani, a great scholarly Sha’fi Sufi sheikh, collected an anthology of Quranic verses and the Prophet’s sayings for neo-converts to chant in mosques so that the habitual hymns-singers do not feel to have been spiritually devitalized.

This peculiarity is ascribed to the circumstances Islam encountered at its formative phase in Kashmir. Ishaq Khan while appreciating the wisdom of Mir Hamadani writes: “It goes to his (Sayyid Hamadani) credit that instead of taking a narrow view of the religious situation in Kashmir, he showed an acute discernment and a keen practical sense in grasping the essential elements of popular Kashmiri religious culture and ethos, and gave creative expression to these in enjoining his followers in the valley to recite ‘Aurad-i-Fatthiyya aloud in a chorus in mosques.” Sayyid according to Khan, “demonstrated a keen sense of practical wisdom and judgement in laying a firm foundation for the gradual assimilation of the folk in Islam.”[ii]

Besides the above-mentioned continuance of age-old practices by the Kashmiri Muslims, there is also belief in many superstitions of the pre-Islamic era. To mention a few here would provide an insight to understand the superstitious behaviour of the people. A cat crossing your path is considered a bad omen and a person would take two and a half steps back to avoid the imminent bad luck. The hold of this superstition is so strong that even today, some people while driving a vehicle would cling to this by driving their vehicle a few meters back. Twitching of eyes is considered highly inauspicious, and a person would do anything from keeping a piece of paddy straw on the upper eyelid to hitting the affected eyelids with a sandal to avoid any bad situation.

There are other superstitions like when a nightingale chirps, visitors are expected; and the superstition of unluckiness of numbers 3, 13 and 23. Even today generally no social function is conducted on these dates of the Christian or Muslim calendar. Kashmiris would also not make nikāḥ (marriage contract) during the months of safar and Muharamas such marriages are believed to be unsuccessful. The strict adherence to different superstitions is an age-old practice, and despite the conversion to a superstition free religion, Islam, the deep imprints of it on Kashmiri psyche are yet to be erased altogether, although it has now a feeble hold on their psyche.

These are some of the practices followed by the Kashmiri Muslims which are often believed to be accretions from Hinduism or the survival of their Hindu past. However, in part II of this article, we will try to assess their religious practices and try to seek the reasons for their ‘lax religious behaviour’.

Endnotes

[i] In this article, the sheikh is used to denote a person chosen by God and endowed with exceptional gifts, such as the ability to work miracles.

[ii] Mohammad Ishaq Khan, Kashmir's Transition to Islam: Role of Muslim Rishis, Manohar Publications, 1994, p.69.

References:

- Q. Rafiqi, Sufism in Kashmir: Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century, Bharatiya Publishing House, Varanasi, n.d.

- M. D. Sufi, Islamic Culture in Kashmir, Light and Life, New Delhi, 1979.

- Imtiyaz Ahmad, Ritual and Religion among Muslims in India, Manohar Publications, New Delhi, 1981.

- Imtiyaz Ahmad and Helmut Reifeld (ed.) Lived Islam in South Asia: Adaptation, Accommodation and Conflict, Routledge, New York, 2018.

- Mohammad Ishaq Khan, Kashmir’s Transition to Islam: The Role of Muslim Rishis, Manohar Publications, New Delhi, 1994.

- “Islam in Kashmir: Historical Analysis of its Distinctive Features.” In Christian W. Troll (ed.) Islam in India, vol. II, Vikas Publications, New Delhi, 1985.

- Muhammad Ashraf Wani, Islam in Kashmir: Fourteenth to Sixteenth Century, Oriental Publishing House, Srinagar, 2004.

(Dr. Bilal Ahmad Sheikh is Assistant Professor of History at Aligarh Muslim University Centre Malappuram. Email Id: bilalfarooq516@gmail.com)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment