The Syncretic Religious Behaviour of Kashmiri Muslims: A Critical Assessment

Part II

In part I of this article I have tried to present a vivid picture of the religious beliefs of Kashmiri Muslims which are often put by sociologists, historians and others into the category of 'diffusion from Hinduism', 'accretions from Hinduism' or the 'survivals' of their past religious behaviour. In this part, my attempt is to reflect upon my own experiences in the field and assess what we have read about them in part I.

For Religious laxity in Kashmir, the Sufis are often blamed as the majority of them were influenced by the waḥdat al-wujūd (unity of being) philosophy of Ibn Arabi. The tombs assumed quasi-divine significance because they have been projected so by the Sufis themselves and later by the shrine bearers. The Sufi graves were termed as khawabgah (sleeping place) and a pīr was ascribed a living character even in his grave who used to listen to and fulfil the wishes of his devotees.

Even the Hadith (sayings of the prophet) that “Allah forbade the soil to consume the Prophet buried in it” was extended to include the bodies of Sufi sheikhs too. They also quoted a tradition that “the Auliya do not die, they [just] go from one home to another home.”

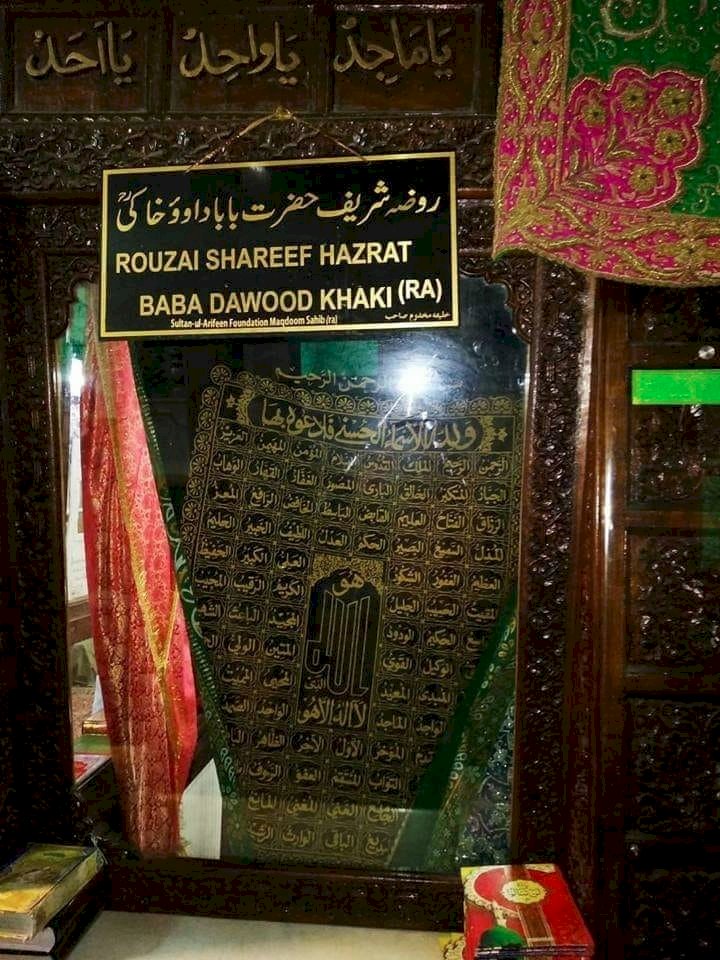

However, what is even more surprising is that Baba Da’ud Khaki, a revered Kashmiri Sufi sheikh(pīr) of 16th century, equates the pilgrimage to and tawaf of the Sufi sheikhs and their graves with the pilgrimage to Makkah and tawaf of Kaʿbah. The reputed Kubravi Sufi-scholar of 16th century Kashmir, Sheikh Ya’qub Sarfi equated the Khanqah of the founder of Kubravi order in Kashmir (Sayyid ‘Ali Hamdani) with Ka’aba.

The same accretion to the sacredness of the tombs was made by Mir- Shams al-Din ‘Iraqi, the founder of Shi’ism in Kashmir who equated seven times circumambulation of his khanqah with earning the same sawab (reward) as one would earn by circumambulation of the Kaʿbah.

The same is true of the followers of Rishis. The disciples of Rishis also tried to ascribe great importance to the visits of the tombs of the founder of the Rishi cult, Sheikh Noor-ud-din Noorani and his immediate khulafa (successors): “Whosoever would go to Chrar, Bumzoo and Muqam [sacred places of Rishis], he would escape from the fire of Hell.” Even it is said that a poor man’s hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) is a pilgrimage to the local shrines.

However, all that has been said about the religious behaviour of Kashmiris should not create an impression that there are ‘two Islams’ in Kashmir; one that is actually practised and the one that is called ‘scriptural’ or ‘textual Islam’. We have the reasons to refute the Orientalist vision of Islamic culture as a split between a ‘normative’ religion of the ‘ulama’ and ‘popular’ religion of the saint-venerating masses.

Despite apparently different collective religious behaviour of the Kashmiris, one cannot even ignore an average Kashmiri Muslim's strong faith in the fundamentals of Islam as revealed in the Holy Quran. They firmly believe in the concept of tauhid, the Quran as the final book of revelation, the finality of Prophethood and the day of the Judgement.

And the assertion that what is often described by an outsider as ‘saint and tomb worship’, is the survival of the Hindu beliefs is also misleading. The veneration of the pīrs is not completely antithetical to the teachings of Islam as they have the status of Awliyā’ (plural of Waliyy) in the eyes of God. What is more unfortunate is that those who create the binary of ‘local Islam’ and ‘universal Islam’ argue so on the basis of what they observe in the outwardly religious behaviour of Muslims without associating the actions or looking at the justification behind within the broader framework of Islamic teachings.

Like in the case of Kashmiri Muslims, Sufi sheikhs or pīrs are revered not because they are some independent entity possessing any supernaturalism independent of Allah. It is rather believed, in consonance with religious teachings, that these religious personalities, free from material desires, who left their comfort and travelled to far off places just to spread the words of Allah are more beloved and nearer to Allah than a lay believer. And then they have the status of Awliyā’ in the eyes of Allah even. The majority of people when making dua at the shrine for fulfilling their wishes do not directly ask it from the Sufi sheikh but from Allah, referring to the Sufi sheikh’s great service to Islam and his piousness as a sort of recommendation.

Instead of judging Muslims’ religious behaviour on the basis of their resemblance with non-Islamic practices, one can look at such practices in the broader framework of Islamic teachings. There were many religious beliefs prevalent among other religions like Judaism and Christianity, which Islam accepted after freeing them of the interpolations. Many beliefs are similar to Islam, Judaism and Christianity as the followers of the other two are considered as 'the people of the book.' It is not that Islam demands the transformation of every single aspect of human emotions, feelings and natural behavioural practice which the essence of religion has nothing to do with. For example, the majority of Muslims while reciting the Quran rock or move back and forth, which is said to be that of the Jewish practice. However, it is not to be taken something against the Islamic teachings rather should be understood as just survival of the behavioural practice which is spontaneous while doing such similar practices and thus is not intentionally done nor ascribed or associated with any belief.

Then there are several other reasons that rather than observing the basic principles of Islam in letter and spirit by the Kashmiri Muslims there was a widespread practice of ‘reverence of Sufi sheikhs and their tombs’ among them. This practice was sustained and became popular only because, as already mentioned above, it was preached and encouraged by Sufi sheikhs. Moreover, as the conversion of mentality is not possible to be achieved overnight such a religious behaviour was allowed so as to provide a channel for maintaining and practising their deeply embedded religious behaviour in Islam but only after completely making them Islamised first and ruling out their conflict with Islam. Thus belief in evil spirits residing in trees and springs is not against the Islamic teachings altogether. Islam acknowledged the belief in the spirits (jinn) even when the concept was also there in the pagan religions before it, though with different elements of belief.

There might be some minor variations between the Islamic concept of the spirits and Sufi sheikhs and how people practise the belief of that, but on the whole, Muslims do not have them as distinct of the Islam itself or in sharp contrast of it rather in conformity with broader teachings of Islam. Thus when an evil spirit is believed to cause a mental delirium to any person, it is not the tantric mantras that are believed to make the evil spirit surrender but the Quranic Ayahs.

Then the lax religious behaviour of Kashmiri Muslims has genuine reasons to remain so for a long time even after the conversion. The Sultans (1339-1586) of medieval Kashmir never made any serious efforts for the institutionalization of Islam in Kashmir. When Kashmir was annexed to and incorporated into the Mughal Empire in 1586, hardly any step was taken in this direction as the rulers were more concerned with the revenue collection and spending their summers in Kashmir gardens. It was only in the 1930s onwards that we see the religious revivalist movement started in Kashmir for purging the Islam of its accretions and superstitions. With a view to restoring its pristine purity. Though it took them decades to bring any substantial change in their desired goals, however, one can now argue with confidence that the Kashmiri Muslims have given up many of such practices which have earned them the epithet of ‘pīr parast’ or for that reason were frowned upon for their laxity in following true religious practices.

Notwithstanding the laxity in following Islam in letter and spirit, Islam made sweeping changes in the overall social behaviour and practices of the converts in Kashmir; in their dress, language, eating habits etc. The Muslims were always more committed to and conscious of their Muslim identity rather than their ethnic or local cultural one. Until recently before their migration from the valley during the 1990s when Kashmiri Hindus along with the Muslims were the part of the Kashmiri society, both of them not only perpetually see themselves as members of distinct religious communities but also 'project their distinct social identities through a series of cultural symbols, including linguistic usage, dress, forms of salutation and other customs etc.'

For example, the Kashmiri spoken by Hindus has been much influenced by Sanskrit words, and the one spoken by Muslims has derived much of its vocabulary from Arabic and Persian. Both the communities were so conscious of their separate identities, religious as well as social and cultural, that they not only projected this separateness in their faith-oriented views, rituals and ceremonies but also maintained it in minute details of everyday life.

References:

- Q. Rafiqi, Sufism in Kashmir: Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century, Bharatiya Publishing House, Varanasi, n.d.

- M. D. Sufi, Islamic Culture in Kashmir, Light and Life, New Delhi, 1979.

- Imtiyaz Ahmad, Ritual and Religion among Muslims in India, Manohar Publications, New Delhi, 1981.

- Imtiyaz Ahmad and Helmut Reifeld (ed.) Lived Islam in South Asia: Adaptation, Accommodation and Conflict, Routledge, New York, 2018.

- Mohammad Ishaq Khan, Kashmir’s Transition to Islam: The Role of Muslim Rishis, Manohar Publications, New Delhi, 1994.

- _______________“Islam in Kashmir: Historical Analysis of its Distinctive Features.” In Christian W. Troll (ed.) Islam in India, vol. II, Vikas Publications, New Delhi, 1985.

- Muhammad Ashraf Wani, Islam in Kashmir: Fourteenth to Sixteenth Century, Oriental Publishing House, Srinagar, 2004.

- N. Madan, Family and Kingship: A Study of the Pandits of Rural Kashmir, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1984.

- ___________” Religious Ideology and Social Structure: The Muslims and Hindus of Kashmir.” In Imtiyaz Ahmad (ed.) Ritual and Religion among Muslims in India, Manohar Publications, New Delhi, 1981.

(Dr. Bilal Ahmad Sheikh is Assistant Professor of History at Aligarh Muslim University Centre Malappuram. Email Id: bilalfarooq516@gmail.com)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment