Glimpses of Muslim Women Scholarship Legacy

Occasionally hit by questions patterned ‘isn't Islam anti-feminist?’ and probed by other incidents, I asked myself to list women scholars in Islam. Apart from the Ummul mu’minīn, no women appeared in my head. However, upon questioning a few, I found that many were in the same boat as I was. 'Where are all the women?! The truth is, the legacy of women's scholarship in Islam is arguably lost and widely unknown amongst Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

In his work, 'Durar Al Karima’, ibn Hajar writes short biographical notes of about 170 women. Amongst 12,043 notables of sahabah his work ‘Al Isabah fi Tamyiz al Sahaba’ mentioned, 1551 were women. Of the scholars Ibn Hajar has marked as the greatest of his time, 1300 were women. Ibn Hajar himself was taught by 53 women. As-Sakhawi had ijazas from 68 women, while 33 women taught As- Suyuti.[1]

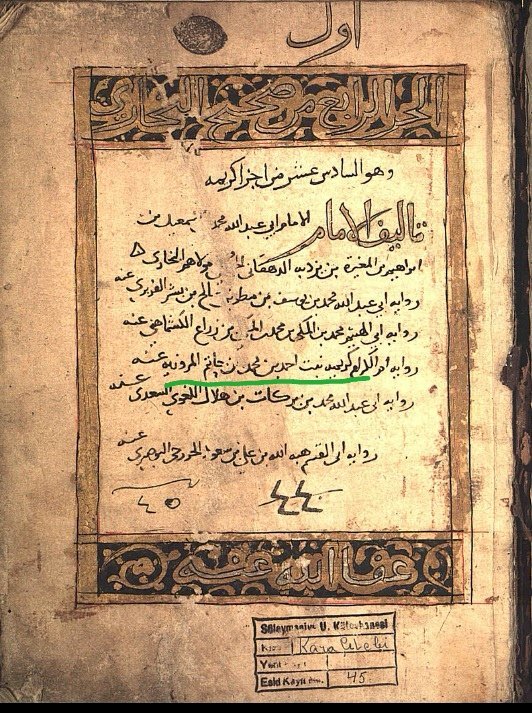

Karima al Marwaziyya (d.463/1073) was considered the best authority of Sahih Al Bukhari in her time. Her scholarship was so esteemed that one of the leading scholars at the time, Abu Dhār of Herat, asked his students to study Sahih under no one else. In fact, Godziher writes: “her name occurs with extraordinary frequency of ijazas for narrating the text of this book.” [2] She had eminent figures like Khatib al Baghdadi and Al Humaydi as her students.

Another example is Amrah binth Abdu-Rahman, a woman scholar among Tabʾīn and granddaughter of As’ad bin Zurarah, a prominent companion of the Prophet. She had a direct chain to ummul Mu’minīn Aisha (R.A.), such that she was privileged of accessing the best resource on hadīth. Sufyan bin ʾUyayna said of her: ‘The most knowledgeable people of the hadiths narrated by lady Aisha were three: Al-Qasim-ibn Muhammad bin Ali Bakr al Siddiq, ‘Urwah ibn Zubair and Amrah binth Abdu-Rahman.’ Being a teacher to the likes of Imam Zuhri, Amrah’s expertise surpassed that of her male contemporaries. Imam Malik’s ‘Muwatta’ narrates an incident where the judge of Madinah at the time, Abu Bakr bin Hazm, sentenced that a Christian thief’s hand be severed. Amrah heard of the case and sent one of her students to the Qadhi. Informing the Qadhi that she was sent by Amrah bint Abdu Rahman, the student said that his judgement was wrong. He cannot sever the man’s hand because the value of what he stole was less than a dinar. The judge followed Amrah’s instruction without a second thought or consulting anyone else, despite Madinah housing seven prominent jurists at the time. “She had rare collections of ahadīth. Umar ibn Abdul Aziz had them copied because he was afraid that knowledge would be wiped off and scholars would disappear.” (Tabaqat Ibn Sa'd v 8. p. 37). [3] He wrote to Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad ibn Amr ibn Hazm, her nephew and student, expressing his concern.

Sahih al Bukhari in the transmission of the famous female Hadith scholar, Karima al Marwaziyya (d. 463 AH). Manuscript from the Karacelebizade library in Turkey.

Umm al Darda’ al Kubra, another gem, taught scholars like Abdul-Malik-bin Marwan, the Caliph. “She was Khayra bint Abu Hadrad Aslarni, wife of Abu Darda. She was very pious, learned, and intelligent (Isti'ab v 2 p. 293). Dhahabi has given the same description of her in Tadhkiratul Huffaz. She narrated many ahadīth directly from the Prophet (PBUH), and then from Abu Darda, Salman Farsi, and ummul mu’minīn Ayshah. Many Tabi'ūn have narrated from her. (Tadhkiratul huffaz v 1 p 50, lsti' ab v 2 p 292)” [4].

Great scholars like Ibn Arabi sought knowledge from women. One of his teachers was Fathima of Cordoba, or Fathima bint Al Muthanna, a 12th century Sufi saint, who was later called his spiritual mother. Ibn Arabi was one of her favourite pupils. All such historical marks prove that it was a norm to have both male and female teachers and mentors for them during their era. They never discriminated among gender when they encountered knowledge and education. They could do so because they were also elevated to great spiritual status. In other words, they were never dry in their religiosity, blindly sticking to the technicalities of religion without understanding the context.

Did Any Privilege Make Them Scholars?

Some might opine that the privileges of these women nurtured their expertise, excelling over their male contemporaries. However, the reality was otherwise. The backgrounds of these scholars were diverse. Abida al Madaniyah, for instance, was a slave, of Muhammad bin Yazeed, who was gifted to Habib Dahhun, a Spanish traditionist on his way to Makkah to perform Hajj. Impressed by her scholarship, Habib freed and then married her and brought her to Andalusia. She has reported many ahadīth from the likes of Malik bin Anas. Her granddaughter, Abda bin Bishr, is a scholar as well. There were many such scholars among slaves, like Munayyah Katibah, Jabrah, Taab al- Zaman etc. In contrast to this, Zaynab bint Suleiman was a princess. Her father was a cousin of Al- Saffah, the founder of the Abbasid dynasty. Thus, their living background was also not a significant factor that contributed to their scholarship.

Maulana Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri’s book ‘The achievements of women scholars in the religious and scholarly fields’ gives an account of women scholars who excelled in Hadith, Fiqh, mathematics, royalty who revolutionized their kingdom, slaves, women who nurtured religious scholars, women in literature etc.

Dr Muhammad Akram Nadwi, a prominent Islamic scholar and the Dean of Cambridge Islamic College, authored a 40-50 volume book named Al Muhaddithath, dedicated to the biographies of women scholars. He started his research on the topic expecting only a few women scholars. But, as he progressed, he found an astonishing number of learned females among Muslims that he had to limit his work to only the scholars of Hadith. Finally, he ended up with 40-50 volumes, with biographies of 10,000 such women.

Reclaiming the Legacy is Imperative

Looking at the life of most scholars in Islam, a noticeable trend was that the scholarship and intelligence of their mothers were more instrumental in moulding them compared to fathers. Women enriched Islam’s intellectual world, both as individuals and groups. For instance, the Otines of Uzbekistan were a group of female scholars and teachers. As cultural caretakers of faith, they safeguarded Islam even when the Soviet policies disrupted it. “The Otines began to learn as children, then at twenty were allowed to commit to a rigorous series of courses and training. At forty, they were given the status of teacher. This system of women teachers preserved outlawed books, traditional knowledge, and moral authority.” [5] Likewise, the Aisyiyah organization of Indonesia, a Muhammadiyah movement of 1917, was established to educate women, fight backwardness, and thwart the Dutch obstructiveness on Islam. Jingshaws, the female teachers of 15th century China, helped preserve and protect Islamic knowledge in the Qing dynasty. Undeniably, women have always actively participated in Islam's educational and knowledge tradition as transmitters, acquirers, supporters, and nurturers of expertise. A rich legacy of Muslim women precedes us, for which we should be thankful, for inheriting the truth from them.

End Notes:

[1] Zainab Aliyah, Great Women in Islamic History: A Forgotten Legacy, young Muslim digest

[2] Goldziher, Muslim Studies, II, 366. "It is in fact very common in the ijaza of the transmission of the Bukhari text to find as middle member of the long-chain the name of Karima al-Marwaziyya," (ibid.); Yaqut, Mu'jam al-Udaba', I, 247 and COPL, V/i, 98f.

[3] Maulana Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri, Achievements of Muslim Women in the Religious and Scholarly Fields

[4] Maulana Qazi Athar Mubarakpuri, Achievements of Muslim Women in the Religious and Scholarly Fields

[5] Fathi, H. (1997). Otines: The unknown women clerics of Central Asian Islam. Central Asian Survey, 16(1), 27-43

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment