Spiritual Oases in the World of Sufis

The path of a Sufi is riddled with hardships. Yet, he walks with content and conviction, placing his trust in his Creator, crossing despicable valleys of greed, lust and vanity unflinching and emerging unscathed. Though you may consider him an entity par-human, his humility will convince you otherwise. The composure on his face, the modesty of his walk and the calmness of his speech do insinuate a peaceful heart, but what may bewilder you is the fact that he is constantly at war with his 'self'. He has attained a voluntary death before the actual one and has thus, transcended life itself. There is so much for us to learn from these larger-than-life characters and so much to inculcate in our daily lives. Let us try, in today's article, to decode the enigmatic lives of the Sufis and understand their engagement practices. Wa billāhi ‘tawfiq

A brief history:

Sufism, also known as ‘Taṣawwuf’ in Arabic derives its name from the word ‘Ṣūf', referring to the woollen cloth worn by the early Sufis. Some believe it has sprouted from the word 'Ṣafāu', which means to cleanse, as the Sufi cleanses his heart from basal tendencies. There is also an opinion having ample support that the word is related to “Ṣuffah” referring to the “Asḥāb as’ Ṣuffah”. The people who used to live their lives unconnected from the world in the shade of “Suffah” (a shelter of palm leaves) inside the Prophet’s ﷺ Masjid. [1]

Whatever may be the lexical origin, the concept of Sufism has strong roots at the beginning of Islam. There are verses of the Qur'ān which address the ailments of hearts and call for their cleansing. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ at various instances emphasized treating the heart as a sanctuary and purifying it of spiritually toxic elements. In the Ḥadīth of Jibreel, the mentioning of Iḥsān after Imān and Islam is linked directly to the spiritual aspect of religion, which is meant by the 'tasawwuf’ in reality. [2]

There have been numerous prominent Sufis over fourteen centuries since the advent of Islam, to name a few:

Owais al-Qarni, Hasan al-Basri, Mālik bin Dīnar, Rābiỵā al-Basariyyah, Fuḍhayl bin Ịyaḍh, Ibrāhīm bin Adham, Bishar al-Hāfī, Dhun' Noon al-Miṣrī, Abu Yazīd al-Bistāmi, Ṣufīyān al-ṭhawri, Ma'roof al-Karḳhi, Sirri al-Saqtī, Junayd al-Bagḥdādi, Ibn Ạta’ Allah al-Iskandari, Husyan Manṣoor Hallāj, Abu Bakr Shibli, Abu Ali Daqq̄aq, Abul Qāsim al-Qushayri, Farīd Uddin al-Attār, Mevlana Jalal Uddin al-Rumi, Abdul Qadir al-Jeelani, Muin Uddin al-Chishti, Aḥmad Riḍā al-Qadri, etc. (Allah is pleased with them) [3]

All of whom have played a crucial role in the propagation of Islam and Sufism in their respective epochs. Thus, Sufism can be carefully termed as Islam's spiritual or esoteric aspect. Now, let us look at the engagement practices.

Sufi engagement practices:

The Orders (Ṭarīqah/Silsila):

The laws formed in the early centuries for the preservation of sacred texts enabled the concepts of "Isnād" (authority). If one wished to quote anything from the religion, he was entitled to possess a sound authority of the same. This authority was often transferred orally from one narrator to another, and the preceding narrator had to confirm his authority from someone preceding him and this way, the authority needed to be traced back to the Saḥaba and ultimately the Prophet ﷺ himself.

Stringent policies were adopted in the transmission of Prophetic narrations and the Recitations of the Qur'an so that the authenticity of the texts remained intact and unquestioned. Likewise, the same policy had to be adopted to transfer the spiritual blessings throughout Sufi orders or Ṭarīqah(s).

These Ṭarīqah/Silsila(s) (Sufi orders), were micro-communities within the Islamic world and were named after their founders. Each had its own particular practices, litanies, specific flavours of teachings and rules. All the orders were unanimous in their core beliefs and practices (referring to core Islamic values, beliefs and commandments); the only differences were in secondary matters. Each order possessed its own chain of transmission which followed back to its founder and ultimately to the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

Thus, one way of the Sufi interaction was identifying oneself as a disciple of a particular order. This gave every individual, treading the path, his own separate identity; and provided a collective place of like-minded individuals to attain his spiritual aspirations.

If one wished to be identified with a particular order, he had to be initiated as a disciple of the order. This would be done by swearing his allegiance at the hands of a Sufi master. In many cases, the disciples had to earn their place by carrying out acts of service in society or increasing their piety.

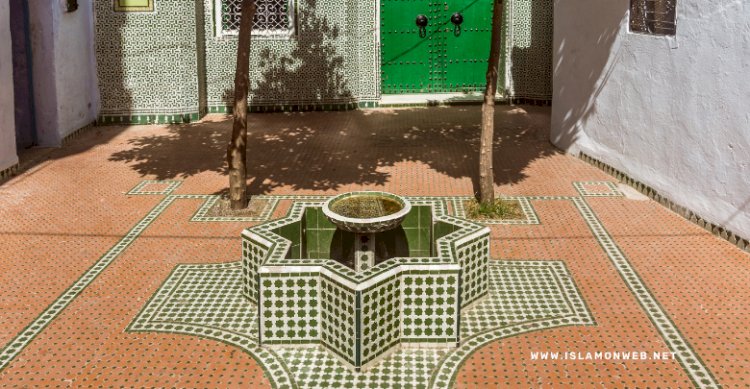

The Zāwiyah/Ḳhānqāh (Sufi community centres):

These were structures that harboured the Sufis. Masters lived, disciples trained, and people attended Sufi gatherings within the confinements of these solemn structures. If we look into the lives of the early and mid-century Sufis, much of their social engagement revolved around these centres. Usually, there would be a Maktab/Mạ’had (elementary school) next to the Zāwīyah for young students to learn the sacred sciences. For centuries, these structures have served as prominent capitals of Islamic Dạ’wah and preaching to the ordinary people.

One can think of them as Open Education centres. If you wished to learn about the Sufi order, their practices or Islam in general, you could, without a second thought, show up at their doorstep and would be welcomed with open arms. People were fed, clothed and groomed in these places, free of charge. The activities were based on the sole generosity of towners or openhanded donations from the nobility.

Nevertheless, the Zawiyah/Khanqah(s) were much more than centres of exoteric knowledge. They were training camps of disciplining the mind and body to gain control of the “self" and fight the basal instincts. This would enable a person to command his ‘inner self’ at will and transcend the apparent world revealing the esoteric realities. Thus, they were places of spiritual awakenings, profound realizations and chances to delve into the abstruse trance of undying Love.

The interior of the Sufi centres would have all the basic amenities. Quarters for masters and disciples to live, common rooms for gatherings, dining halls for people to eat together, classrooms to train new disciples and of course community Masjids for everyone to pray. This description goes without saying that such a structure housed a strongly cohesive community.

A practice worth mentioning here is the “Murāqbah" or Group meditation sessions of the Sufis. Here, they would often gather around in a specific room forming a circle, the Master would be at the heart of it, and one of the disciples would start chanting the litany. Usually, it would be the Ism al-Aạzam of the Almighty or any special litany unique to the order. Everyone else would repeat after him. This would continue, and the halls would echo with chants of 'Allah! Allah!' in unison. [4]

Thus, the centres would emerge as a Universe of their own, providing a living space for the Sufi traditions and acting as epicentres of humanitarian aid and community service.

Modes of Interaction:

Most of the Sufi engagement revolved around communities in a one-to-many master-disciple relationship. Thus, most of the teachings were based on oral transmission through sermons. A master would address his disciples through a pulpit, and the gathering would listen, take notes and commit to memory.

This mode of interaction reached its pinnacle during the age of Shaykh Abdul Qadir al-Jeelani, who has been reported to address approximately 70,000 listeners in a single meeting where as many as 400 disciples would gather with pens and papers to jot down the Shaykh's preaching. Historical accounts report that his address was hosted in numerous places, ranging from the Jame’ Masjid Kufa (Congregational Mosque) to the Eid Gaah of Baghdad and to the Outskirts of the city where a remarkable pulpit was installed for him. [5]

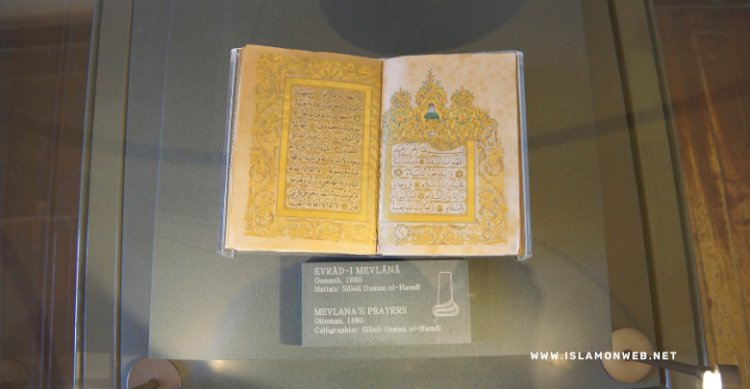

Another prominent way of interactions among the Sufis was through letters. Sufi masters and learned Sufi scholars would write letters to people from all walks of life. They would address their disciples in different cities by sending them letters of admonishment. Often, many people would become disciples through writing to the Shaykh and the Shaykh replying with acceptance. Letters played an important role in the process, as they were firm documentation that could be referred to as and when needed.

This mode was followed by many Sufi masters and flourished throughout the centuries, particular mentions would be Imam al-Ghazali who wrote numerous letters to his disciples, ordinary folks, kings and nobility, and to fellow Sufis as well. Shaykh Abdul Qadir al-Jeelani is also said to have written numerous reforming letters himself.

However, a particular mention here must be made of Imam al-Rabbani Shaykh Ahmad al-Sirhindi, better known as Mujaddid Alf Thani, as a large chunk of the Shaykh’s legacy is in the form of his letters. These letters range from being sent to Kings, Courtiers, Traders, Disciples, Sufi masters, Commoners and even to non-Muslims. Approximately 536 letters have survived and have been compiled into three volumes named "Maktoobāt-i-Imām-i-Rabbāni”. [6]

An interesting mode of interaction among Sufis has also been through one-to-one coaching. The master would pick out a select few from amongst his disciples in whom he would sense the potential for spiritual success. He would then guide them personally and give special attention to their spiritual growth; these people, in turn, would go on to become Sufi masters of their own and establish branches of the order. This method is not intrinsic to all Sufi orders, but high degrees of it are exclusive to a particular few, such as the Naqshbandi Sufi order.

This order has thrived greatly on personal coaching and single-ended interactions. A master would travel, with his limited disciples, town to town until he would find a suitable environment to establish the Ḳhānqāh. In the event of him finding suitable disciples there, in which he would foresee spiritual success, he would set up his lodging in nearby places or outskirts of the city. A place would be chosen which could promise solitude and a calm environment. There, disciples would be trained properly to become self-conscious as well as God-fearing.

Thus, the Shaykh would direct his attention to the choicest few disciples and grow them into masters of spiritual realities. It would not be in vain to mention a pragmatic example near my own city Pilibhit. Shaykh Jamāl Ullah al-Rampuri was a master of the Naqshbandi Sufi order, he would often come to Pilibhit, wherein he would train disciples and preach commoners. Among the ones he encountered, he gave his spiritual authority to only a select bunch, namely: Shaykh Ne’mat Ullah Shah, Shaykh Subhān Ullah Shah, Shaykh Muḥammad Sher, Shaykh Lutf Ullah Shah. Thus, these Shaykhs are said to have his special attention as well as personal mentorship and all of them emerged as glimmering spiritual epicentres of their time. [7]

Thus, to sum up, we looked into the lexical meanings of Sufism, took a bird's eye view of the early Sufi masters, came to know about various Sufi structures, practices and peculiarities. Then, we took a deep dive into the Sufi modes of interaction and tried to understand how they lived and transmitted their timeless knowledge. Finally, we understood all of that with pragmatic historical examples.

To conclude, I’d like to say that, yes, the Sufi path is riddled with hardships. To tread it is difficult, to understand it, even more so. But as I once wrote,

So, the bittersweet pain

Of the rocky trails,

Cannot prevent the fits.

Of human souls from showing the most

Beautiful innate bits…

There will always be seekers, and there will always be finders, but the fact that matters is do we choose to "search" or do we just "ignore"…

References and Citations:

[1] al-Hujveri; Syed Ạli bin Uṭhmān; Kashf ul Mahjoob; Urdu Translation; under the heading: “Discourse about tasawwuf” Published Muhammadi Book Depot.

[2] al-Nawawī; Yaḥyā bin Sharaf; Arbạeen lil-Imām al-Nawawī; Hadith #2.

[3] al-Attār; Farīd Uddin; Tadhkirat ‘ul-Auliyā; Urdu Translation; Published Razvi Kitab Ghar.

[4] al-Hujveri; Syed Ạli bin Uṭhmān; Kashf ul Mahjoob; Urdu Translation; under the heading: “The terminology of Sufis” Published Muhammadi Book Depot.

[5] al-Dehlvi; Shaykh Ạbdul Haque; Seerat-i-Ghawth-al-Aạzam; Published Al-Barkāt Research and Training Institute.

[6] al-Sirhindi; Shaykh Ahmad; Maktoobāt-i-Imām-i-Rabbāni; Compiled: Khwaja Yar Muhammad Badakhshi, Khwaja Abdul Hayy, Khwaja Hashim Kazmi.

[7] Haider; Khawaja Razi; Tadhkira Muhaddis-i-Soorati; Published Raza Academy Mumbai.

(Fardeen Ahmad Khan Razvi is a renowned Oriental Research Scholar who has authored over a hundred articles and twenty-plus booklets on Islamic and other Oriental subjects in Arabic, English, Urdu and Hindi languages. His minor is in Computer Applications pursuing his Major in Data Science. He is also an eloquent Urdu poet coming from a Sufi background in Northern India)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

2 Comments

-

Great article. There will always be Saints, Sufis Masters, Murshid or Shaikh present in the world and equally there will be the seekers of the Divine. When one strives to find that perfect spiritual guide who can lead the seeker to Mohammadan Assembly, Allah opens the ways for him or her. To know about the perfect spiritual guide of this era visit the link below sultan-ul-ashiqeen.pk

-

Read Mahnama Sultan ul Faqr Magazine and know about Sufism. Mahnama Sultan ul Faqr Magazine is the only representative of Faqr in the world.Its sole purpose is to spread the teachings of Faqr and invite Muslims towards purity of soul. The sole purpose of this magazine is invitation towards Faqr and spread the teachings of the Sarwari Qadri Saints. http://mahnama-sultan-ul-faqr-lahore.com

-

Noor

2 years ago

http://mahnama-sultan-ul-faqr-lahore.com

-

Leave A Comment