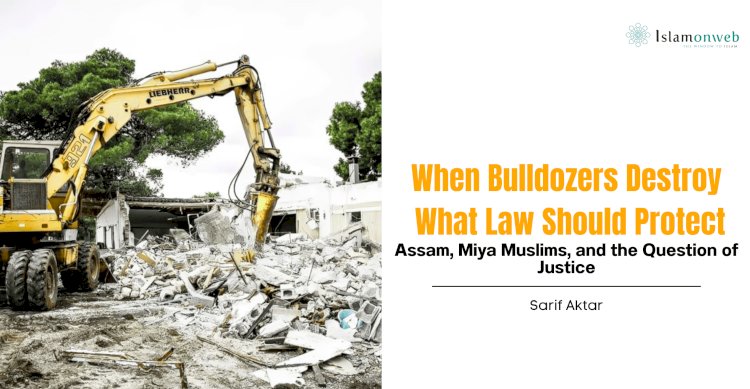

When Bulldozers Destroy What Law Should Protect: Assam, Miya Muslims, and the Question of Justice

“Let not the hatred of a people prevent you from being just. Be just — that is nearer to righteousness.” (Qur’ān 5:8)

Introduction

In recent years, the northeastern Indian state of Assam has witnessed a troubling pattern of state-led demolitions targeting Miya Muslim settlements. These drives, often justified as “anti-encroachment” measures, have increasingly been executed without prior notice, rehabilitation plans, or adequate judicial oversight. The bulldozer has thus come to symbolize not only a machine of demolition but also the erosion of constitutional guarantees of equality and due process.

The issue is not confined to infrastructure or land policy. It raises fundamental questions about citizenship, identity, and the rule of law in a democracy. Assam’s Miya Muslims a community largely descended from Bengali-origin peasants who migrated generations ago to the Brahmaputra Valley continue to face suspicion over their legal status despite possessing electoral rolls, land records, and Assamese language fluency (Hussain, 2019). In public discourse, they are often reduced to “illegal Bangladeshis,” a label that delegitimizes their rights and normalizes collective punishment.

This essay narrows its focus to the intersection of bulldozer politics, constitutional protections, and Miya Muslims’ struggle for belonging, while drawing upon Islamic ethics as a comparative framework. By situating Assam’s demolitions within both Indian constitutional law and broader moral traditions, it seeks to highlight the gap between what justice promises and what justice delivers.

Bulldozers Over Human Dignity: The Miya Muslim Crisis in Assam

On 20 June 2022, authorities in Assam’s Darrang district demolished dozens of houses in the Garukhuti area, leaving nearly 1,000 families homeless (Amnesty International, 2022). Visuals from the eviction showed police firing on protesting villagers, killing at least two people including a 12-year-old child (Human Rights Watch, 2023). The demolitions were part of what the state government called an “anti-encroachment” initiative to clear land for agricultural projects. Yet independent observers noted that most affected residents were Miya Muslims who had been living there for decades, paying taxes and voting in elections (Hussain, 2019).

These incidents are not isolated. Bulldozer-led demolitions have taken place in Sipajhar, Nagaon, and Dibrugarh districts since 2021, often without following the safeguards outlined by the Supreme Court of India. In Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985), the Court held that the right to livelihood is part of the right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution, and thus evictions without rehabilitation violate fundamental rights. More recently, in 2022, the Supreme Court cautioned states that “demolitions cannot be retaliatory” and must comply with established legal protocols (The Hindu, 2022).

Despite these precedents, reports from Assam indicate a bypassing of due process. Notices are either absent or issued too close to demolition dates to allow effective legal recourse. Residents are rarely provided alternative housing, contradicting India’s obligations under both domestic law and international human rights standards (Amnesty International, 2022). The practice undermines Article 14 (equality before law) and Article 21 (protection of life and personal liberty), both cornerstones of the Indian Constitution.

Beyond legality, these demolitions deepen a sense of systematic marginalization. By framing Miya Muslims as “encroachers,” state narratives risk turning citizenship into a conditional status dependent on ethnicity and religion. This aligns with what analysts describe as “demographic re-engineering” in Assam (Barua, 2020). What is presented as neutral land policy, therefore, functions as a political tool of exclusion.

The Prophet ﷺ and Mercy as Political Strength

When the Prophet ﷺ re-entered Makkah after years of persecution, he stood in a position where revenge was expected. Instead, he declared: “No blame will there be upon you today. May Allah forgive you; and He is the Most Merciful of those who show mercy.” (Qur’ān 12:92). His response was not to destroy homes or displace families, but to restore dignity and belonging.

This episode highlights an ethic of governance rooted not in retaliation but in justice and reconciliation. Islamic political philosophy consistently upheld the idea that the state’s legitimacy depends on protecting the weak, including minorities and adversaries. For example, the Prophet ﷺ warned: “Whoever wrongs a dhimmī (non-Muslim under Muslim protection), diminishes his right, burdens him with more than he can bear, or takes something from him without his consent, I will be his opponent on the Day of Judgment.” (Sunan Abū Dāwūd 3052).

Contrasted with Assam’s bulldozer politics, these teachings remind us that justice cannot be selective. Where due process is bypassed and entire communities are branded “illegal,” law becomes an instrument of exclusion rather than protection. Islamic ethics, while not the main framework of India’s governance, offer a comparative lens to measure how mercy, accountability, and restraint can strengthen rather than weaken political authority.

Constitutionalism and the “Mirage of Neutrality”

The Indian Constitution, at least in principle, promises equal treatment. Article 14 guarantees equality before the law, Article 21 protects life and dignity, and Article 25 ensures freedom of religion. Yet, in practice, Assam’s demolitions demonstrate how majoritarian politics can override constitutional safeguards. Miya Muslims, despite generations of residence, continue to be asked to prove their citizenship often multiple times through processes like the National Register of Citizens (NRC) only to face further precarity when bulldozers arrive.

Secularism, in this sense, risks functioning more as a veil of neutrality than as a genuine guarantee of protection. The absence of impartial enforcement means that laws meant to protect all citizens equally end up disproportionately applied against marginalized groups.

In Islamic governance, by contrast, justice was not contingent on neutrality but on taqwā (God-conscious accountability). Historical precedents from the Caliphate, such as Caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (RA) submitting to a judge’s verdict in favor of a Christian litigant (Al-Māwardī, 1996), illustrate a system where rulers were bound by law rather than above it.

The comparison is not to propose a religious state for India, but to show that constitutionalism must be judged by how it protects its most vulnerable, much as Islamic ethics insisted on fairness even for non-Muslims and political rivals.

Why Due Process Matters

The bulldozer may appear efficient as a tool of governance, but its use outside legal safeguards erodes the very rule of law that anchors democracy. Each demolition without notice undermines judicial authority; each family displaced without rehabilitation weakens public trust in institutions. If the Constitution is to retain meaning for all citizens, then Assam’s policies must align with both domestic legal precedents and international human rights norms.

Here, Islamic ethics serve less as an alternative blueprint and more as a moral reminder: justice cannot exist without accountability, and power without restraint leads to oppression. The Prophet ﷺ and his successors demonstrated that political strength is best expressed through fairness and protection of dignity, not its violation.

Conclusion

The plight of Assam’s Miya Muslims illustrates the dangers of allowing administrative convenience to eclipse constitutional duty. Bulldozer demolitions carried out without due process not only devastate lives but also undermine the very promise of equality and justice that India’s legal framework enshrines. Comparative insights from Islamic ethics underscore that true authority lies not in might but in justice, not in exclusion but in protection. Just as the Prophet ﷺ forgave those who once drove him into exile, a modern democracy must extend rights even to those it perceives with suspicion. For Assam, the path forward requires more than halting demolitions. It requires restoring faith in due process, judicial oversight, and constitutional guarantees. Only then can the bulldozer cease to be a symbol of fear and become part of lawful governance. And only then can India’s secularism move from a fragile promise to a lived reality.

About the author

Sarif Aktar is a Political Science undergraduate at Gauhati University, Assam, and a postgraduate student in the Study of Religions at Darul Huda Islamic University, Kerala. His research explores the intersection of religion, society, and law, with a focus on gender justice and constitutional ethics.

References

- Amnesty International. (2022, June 28). India: Stop unlawful demolitions of Muslim properties in Assam. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/06/india-assam-unlawful-demolitions/

- Barua, S. (2020). Political violence and ethnic identity in Assam. Routledge.

- Human Rights Watch. (2023, January 17). India: Discriminatory policies against Muslims in Assam. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/17/india-discriminatory-policies-assam

- Hussain, M. (2019). The plight of the Miya Muslims of Assam. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(27), 14–18. https://www.epw.in/journal/2019/27

- The Hindu. (2022, April 21). Supreme Court cautions against using demolitions as punitive measure. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/supreme-court-on-demolition-drives/article65342642.ece

- Al-Māwardī, A. H. (1996). The ordinances of government (Al-Aḥkām al-Sulṭāniyya) (W. H. Wahba, Trans.). Garnet Publishing. (Original work published 1058).

- Qur’ān. (n.d.). The Noble Qur’an (Saheeh International Trans.). Abul Qasim Publishing House.

- Abū Dāwūd, S. (2008). Sunan Abī Dāwūd (H. Siddiqi, Trans.). Dar-us-Salam. (Original work published 9th century).

- Supreme Court of India. (1985). Olga Tellis & Ors vs Bombay Municipal Corporation & Ors, AIR 1986 SC 180.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment