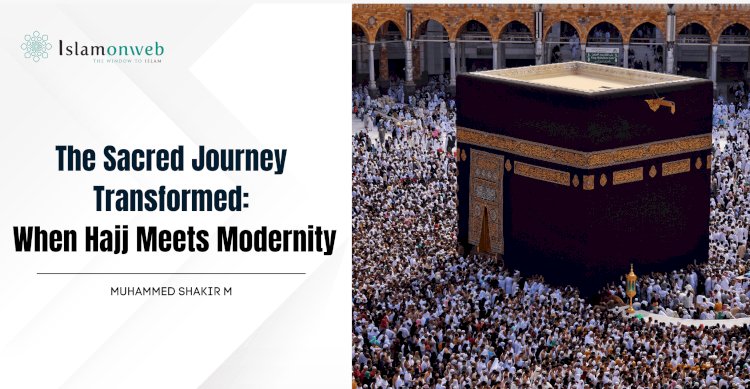

The Sacred Journey Transformed: When Hajj Meets Modernity

The verdant island of Lombok in Indonesia offers a compelling window into a transformation unfolding across the Muslim world. Here, as in many Islamic communities globally, the sacred journey of Hajj has evolved from a purely spiritual undertaking into a complex social phenomenon that reflects the tensions between religious tradition and modern life.1 What unfolds in this Southeast Asian community mirrors broader patterns of change affecting Islam's holiest pilgrimage worldwide.

The completion of Hajj has long carried implications beyond the spiritual realm. For centuries, returning pilgrims have received honorific titles and elevated social standing—a pattern visible not only in Indonesia but across Muslim societies from West Africa to Southeast Asia.2 This transformation reflects Islam's unique capacity to create alternative pathways to status and respect, allowing devotion to transcend traditional social hierarchies.

Yet this elevation has always carried responsibility. A returning pilgrim faces heightened expectations—to demonstrate both the financial capability that funded their journey and the religious legitimacy befitting someone who has stood before the Kaaba. When pilgrims fall short of these expectations, communities may question whether their Hajj was truly mabrur (accepted by Allah)—a judgment that reveals how inextricably religious and social dimensions have become intertwined.

The historical trajectory of Hajj reveals a gradual evolution in its meaning and practice. In earlier generations across the Islamic world, those who made the arduous journey to Makkah often remained in the holy city for extended periods, dedicating themselves to scholarship before returning to their communities as respected religious leaders and teachers.3 Colonial powers—whether Dutch in Indonesia, British in South Asia, or French in North Africa—inadvertently elevated the prestige of Hajj through their suspicion of returning pilgrims as potential anti-colonial agitators, adding political significance to an already spiritually meaningful journey.4

Throughout Muslim societies, elaborate communal rituals have traditionally surrounded both departure for and return from Hajj. Pre-departure ceremonies serve as public announcements of the pilgrim's intentions and financial capacity, while post-return celebrations where Hajjis share stories of their experiences strengthen community bonds. These practices, visible from rural Indonesia to urban Morocco, reinforce the special status of those who have completed the journey while embedding individual religious achievement within collective celebration.

The motivations driving pilgrims have undergone a significant evolution worldwide. In past generations, Hajj represented a genuinely life-threatening journey—months of travel with no guarantee of return, prompting many to pack burial shrouds alongside their travel necessities. This perilous undertaking was primarily motivated by deep faith, a thirst for religious learning, and a desire to return as a source of spiritual guidance.

Contemporary Hajj, while physically safer, reveals more complex motivations that transcend cultural boundaries. The commercialization of pilgrimage is evident in the proliferation of luxury packages that prioritize comfort and proximity to sacred sites for those who can afford premium prices.5 For some pilgrims, regardless of national origin, the journey has become an opportunity for social media documentation and status acquisition rather than spiritual transformation.

Islamic scholar Dr. Yusuf al-Qaradawi has observed this phenomenon throughout the Muslim world: "When the religious act becomes separated from its spiritual essence and becomes merely an outward display of status or wealth, we must question whether we have maintained the purity of intention (niyyah) that makes our worship acceptable to Allah."6 His concern resonates across national boundaries wherever Muslims navigate the intersection of faith and modernity.

The tradition of Hajj carries profound positive impacts across diverse Muslim communities. At its best, it represents the fulfillment of Islam's fifth pillar, bringing genuine spiritual satisfaction and a sense of religious completion. The aspiration to perform Hajj has historically motivated financial discipline and industriousness among Muslims of modest means worldwide—farmers, laborers, and market vendors who save diligently for decades to realize their dream. The shared rituals surrounding departure and return strengthen community bonds through collective celebration of individual piety.

Yet shadows have emerged alongside these benefits in Muslim communities globally. Many families sell vital assets or incur significant debt to fund the journey, risking long-term financial instability.7 The elevation of Hajjis to elite status creates new forms of class division between pilgrims and non-pilgrims. Perhaps most concerning is the emerging relationship between neo-liberal capitalism and religious practice, where Hajj increasingly resembles a luxury brand experience available in tiered packages corresponding to one's financial means—a transformation visible from Jakarta to Jeddah, from Karachi to Cairo.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) warned against such trends when he said: " "If you see someone buying or selling in the mosque, say: May Allah not make your trade profitable."8 Yet the commercialization of religious experience has proven difficult to resist in an age where market values penetrate nearly every aspect of human activity, challenging Muslims worldwide to maintain spiritual authenticity amid material pressures.

For those unable to afford the increasingly costly journey to Makkah, alternative practices have emerged in various Muslim societies. Visits to local sacred sites serve as an "alternative Hajj" for many—a practice that preserves spiritual meaning while adapting to economic constraints. These localized pilgrimages represent both practical adaptation and subtle resistance to the economic barriers surrounding official Hajj, demonstrating how Muslim communities creatively maintain connection to sacred practice despite financial limitations.9

Critics within the global Muslim community have raised important questions about these transformations. Some ask whether Hajj has become primarily about accumulating symbolic capital rather than deepening one's relationship with Allah.10 Others question whether the increasingly bureaucratized and commercialized management of Hajj—with its waitlists, quotas, and tiered pricing systems—contradicts the fundamentally egalitarian ethos of Islam, where all pilgrims wear the simple white ihram garments specifically to eliminate visible distinctions of wealth and status.

The transformation of Hajj reveals broader tensions between tradition and modernity, between spiritual values and material realities, that transcend any single Muslim society. Yet this evolution should not be viewed simplistically as decline. Throughout Islamic history, religious practices have continuously adapted to changing circumstances while preserving core spiritual meanings—from the early expansion beyond Arabia to the adoption of local architectural styles for mosques to the integration of new technologies for determining prayer times.

The challenge facing Muslims globally is to maintain the essential spiritual purpose of Hajj while acknowledging its unavoidable social and economic dimensions. This requires both individual and collective vigilance against the reduction of sacred experience to status performance—a challenge that transcends cultural boundaries wherever Muslims navigate the complexities of religious practice in the modern world.

Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr suggests: "Modernity need not mean the abandonment of tradition, but rather finding ways to live traditional values authentically within contemporary realities."11 This perspective offers a path forward for Muslims worldwide, recognizing that traditions have always evolved while maintaining continuity with their spiritual foundations.

For Muslims across diverse societies, Hajj remains a powerful spiritual and social force that unifies communities and motivates ethical living, even as its practice adapts to contemporary conditions. The question is not whether change should be resisted entirely—an impossible task—but how to ensure that adaptations preserve the sacred essence that gives meaning to the journey.

As one elder pilgrim reflected: "When my grandfather performed Hajj eighty years ago, he traveled for months by boat and nearly died of illness in Makkah. Today my grandson flies there in comfort. The journey has changed, but Allah's house remains the same. What matters is the heart we bring to it."

In this perspective lies wisdom for navigating not just the transformation of Hajj, but the broader relationship between Islamic traditions and modern life—recognizing change while holding fast to the eternal principles that give our practices their deeper meaning. The challenge of maintaining spiritual authenticity amid material transformation is one that unites Muslims across geographical, cultural, and economic differences—a shared struggle to honor tradition while living fully in the present.

About the Author

MUHAMMED SHAKIR M is a graduate student in Civilizational Studies at Darul Huda Islamic University, focusing on the intersection of religious practices and modernization processes in Muslim societies. Their research examines how traditional Islamic rituals adapt to contemporary socioeconomic conditions while maintaining spiritual integrity. With a background in comparative religious studies and an interest in cultural anthropology, they explore how communities navigate the tensions between sacred traditions and modern realities. Their current work investigates pilgrimage practices across different Muslim societies as windows into broader patterns of religious transformation in the globalized world.

Endnotes

- Tagliacozzo, E. (2013). The Longest Journey: Southeast Asians and the Pilgrimage to Mecca. Oxford University Press. ↩

- Bianchi, R. (2004). Guests of God: Pilgrimage and Politics in the Islamic World. Oxford University Press. ↩

- Azra, A. (2004). The Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia: Networks of Malay-Indonesian and Middle Eastern 'Ulama' in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of Hawaii Press. ↩

- Laffan, M. (2003). Islamic Nationhood and Colonial Indonesia: The Umma Below the Winds. Routledge. ↩

- McLoughlin, S. (2013). "Organizing Hajj-Going from Contemporary Britain: A Changing Industry, Pilgrim Markets and the Politics of Recognition." In The Hajj: Collected Essays, edited by V. Porter and L. Saif. British Museum Press. ↩

- Al-Qaradawi, Y. (2011). Fiqh al-Hajj. Cairo: Dar al-Shorouk. ↩

- Haq, F., & Jackson, J. (2009). "Spiritual Journey to Hajj: Australian and Pakistani Experience and Expectations." Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 6(2), 141-156. ↩

- Narrated by al-Tirmidhī (ḥadīth no. 1321); graded ḥasan by al-Tirmidhī.. ↩

- Eickelman, D. F., & Piscatori, J. (1990). "Social Theory in the Study of Muslim Societies." In Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination, edited by D. F. Eickelman and J. Piscatori. University of California Press. ↩

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). "The Forms of Capital." In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson. Greenwood Press. ↩

- Nasr, S. H. (2010). Islam in the Modern World: Challenged by the West, Threatened by Fundamentalism, Keeping Faith with Tradition. HarperOne. ↩

More Related Articles

Eid al-Aḍḥā Through the Quran, Torah and Bible: Unity in Diversity

Hajj of Heart and Heart of Hajj

The Significance, Spirituality and Wisdom of Qurbani

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment