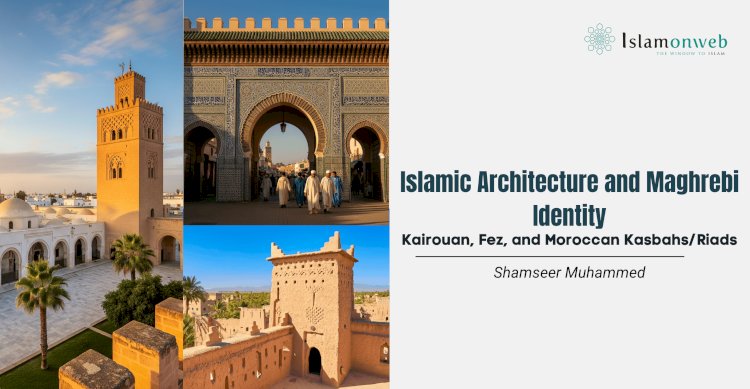

Islamic Architecture and Maghrebi Identity: Kairouan, Fez, and Moroccan Kasbahs/Riads

Islam reached North Africa in the 7th century, introducing new urban and architectural forms that blended seamlessly with local Berber traditions and Mediterranean influences. Over the centuries, this syncretism produced a distinct Maghrebi-Islamic style, visible in sacred cities, centres of learning, and domestic architecture.

In Tunisia, Kairouan, founded in 670 AD, emerged as Islam’s first stronghold in the western Islamic world, home to the Great Mosque of Kairouan. In Morocco, Fez, established around 789 AD, grew into a dynastic capital, its heart marked by the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and University, founded in 859 AD. Across Morocco, fortified kasbahs and inward-looking riads (courtyard houses) embody both adaptation to desert climates and the preservation of Islamic social values.

This essay examines the history and design of these monuments, highlighting how their form, function, and decoration reflect the intertwined Islamic and Maghrebi cultural identity. Key references include UNESCO heritage reports and scholarly studies on the architecture of the Maghreb.

Historical Background of Islam in the Maghreb

The Arab general ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ founded Kairouan in 670 AD as a military outpost, which later developed into the provincial capital of Ifriqiya. Under the Aghlabids (9th century) and subsequent dynasties, Kairouan became a leading religious and cultural centre. Built upon earlier Berber settlements and Roman sites, early Maghrebi cities typically featured narrow medina streets, central mosques, and palm groves sustained by arid-land irrigation systems. Islamisation introduced the jāmiʿ (Friday mosque) as the focal point of urban life. In medieval Kairouan, for instance, the city plan revolved around the Great Mosque and its adjacent market, forming the spiritual and economic heart of the community.

In the 8th–9th centuries, Fez (Morocco) was founded by the Idrisid dynasty and became home to major religious and scholarly institutions. Fatima al-Fihri (d. 880) established the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and madrasa in 859 AD within Fez’s medina. Later Moroccan dynasties - the Almoravids (11th–12th centuries), Almohads (12th–13th centuries), and Marinids (13th–15th centuries) - expanded the city and enriched it with sophisticated architectural decoration. Following the fall of Córdoba (11th–15th centuries), many Andalusian Muslims and craftsmen sought refuge in Fez, bringing Iberian elements such as distinctive arches and muqarnas into local design. Overall, Moroccan Islamic architecture blended indigenous Amazigh (Berber) traditions, such as rammed-earth construction and plain geometric carving, with Andalusi-Islamic features, including horseshoe arches and zellij tilework, to create a distinctive hybrid style.

In the deserts and rural areas, fortified settlements known as ksour or ksars, more widely referred to as kasbahs, were constructed to protect oases and secure trade routes. UNESCO describes a kasbah as “earthen buildings with high walls… supported by corner towers.” In urban contexts, however, residential life centred on riads: multi-level houses arranged around a secluded inner garden or courtyard. These designs optimised shade and ensured privacy, in harmony with Islamic social values—a subject explored further in the next section.

The Great Mosque of Kairouan

Historical Development

The Great Mosque of Kairouan (Masjid ʿUqba) was established shortly after the city’s foundation (c. 670 AD) by ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ and rebuilt in successive phases. The structure we see today is largely a 9th-century Aghlabid construction. It is the fifth mosque on the site. While later repairs have been undertaken, the original plan has remained remarkably intact, making it one of Islam’s most enduring monuments.

As UNESCO notes, Kairouan is one of the oldest Islamic cities in the Maghreb (founded 670 AD) and long served as a “principal holy city.” The Great Mosque projected both religious authority and political power, much like the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus did for the eastern Islamic world. Medieval Arab geographers and later pilgrims praised Kairouan as Islam’s “Fourth Holiest City” after Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. This spiritual prestige is embedded in the mosque’s architecture: its solid form and repeated reconstructions testify to its sanctity and enduring centrality.

Architecture and Design

Architecturally, the Great Mosque of Kairouan is a hypostyle complex that blends Roman, Byzantine, and local North African elements. The prayer hall, measuring about 135 by 80 metres, comprises 17 longitudinal aisles supported by nearly 400 columns, creating what has been described as a “forest” of marble and porphyry. Most of these columns are spolia from nearby Roman and Byzantine sites, their Corinthian capitals displaying a mix of reused classical designs and hand-carved motifs.

The aisles lead towards the richly decorated mihrab (prayer niche) and the carved wooden minbar (pulpit), both of exceptional historic value. In front of the prayer hall’s southern entrance is an intricately carved wooden-lattice screen, among the oldest surviving in the Islamic world. The hall’s arrangement, rows of columns beneath a flat timber ceiling adorned with hanging lamps, exemplifies early Maghrebi mosque design.

Beyond the prayer hall lies a vast flagstone courtyard, framed on three sides by arcaded porticos. To the north stands the square minaret, rising 33 metres high. With its stepped pyramidal form and buttressed corners, it is the oldest surviving minaret in the Muslim world and served as the prototype for later Moroccan and Andalusian towers. A smaller dome above the mihrab is also an important early feature. The mosque’s thick adobe enclosure walls, up to 1.9 metres thick, give it a fortress-like appearance, a characteristic common in Maghrebi mosques. Overall, it combines the formal simplicity of the hypostyle plan with refined classical decoration, balancing monumental dignity with functional adaptability.

Cultural Significance

The Great Mosque remains the defining symbol of Kairouan. UNESCO describes it as a “universal architectural masterpiece.” Its uninterrupted use for over 1,300 years testifies to the resilience of Islamic urban life in North Africa. As the nucleus of the early city, it shaped the surrounding network of narrow souks and residential quarters.

From medieval times, the mosque was not only a place of worship but also a centre of learning, housing scholars and serving as a repository of books and teaching, thus prefiguring the mosque-university complexes of Fez. Architecturally, its uniform colonnades and robust ramparts embody Islamic principles of unity, order, and communal equality. Its incorporation of ancient Roman and Byzantine columns symbolises continuity with North Africa’s pre-Islamic past, reinterpreted under the banner of a new faith.

Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and University, Fez

Historical Development

The Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque (جامع القرويين) in Fez was founded in 859 AD by Fatima al-Fihri, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Initially, it served a local community of immigrants from Kairouan. Over time, the mosque evolved into a vast complex incorporating a madrasa and a library, becoming one of the most renowned centres of Islamic scholarship. UNESCO and historians regard Al-Qarawiyyin as the world’s oldest continuously operating university; as noted in the UNESCO inscription for Medina of Fez, it is “the oldest university in the world.”

The mosque’s expansion reflects the patronage of successive Moroccan dynasties. The Almoravids (11th–12th centuries) and Almohads (12th–13th centuries) played pivotal roles in enlarging and embellishing it, followed by the Marinids and Alaouites (13th–18th centuries). Each era left behind distinctive layers of decorative and structural detail, mirroring wider Islamic architectural trends. In this way, the history of Al-Qarawiyyin is inseparable from Fez’s identity as an enduring seat of Islamic learning.

Architecture and Design

Like the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Al-Qarawiyyin developed around a central courtyard (ṣaḥn). By the late 19th century, travellers described a spacious square courtyard with a fountain and arcaded colonnades. Early sources and recent scholarship indicate that the original mosque was a modest “oratory of about 100 m²,” with only four aisles, a single minaret, and a courtyard.

The Almoravids undertook major expansions, introducing ornamental elements inspired by Andalusian design. According to the Islamic Art Museum, their 11th-century restoration “enlarged and enriched it with elements borrowed from the Andalusian ornamental style… plasterwork sculpture, muqarnas domes, sculpted marble capitals, epigraphic and geometrical floral motifs.” Surviving stucco fragments and carved wood testify to the period’s fine craftsmanship.

During the Marinid period (13th–15th centuries), the prayer hall was extended to accommodate 270 columns arranged into 16 aisles, and a massive chandelier holding about 500 lamps was installed. The mihrab and doorways were adorned with Kufic inscriptions and arabesque tilework, echoing motifs from contemporary Andalusi mosques. The mosque’s green-tiled pyramidal rooftops and small domes, still visible today, are characteristic features of Moroccan roofscapes.

The layout reflects a synthesis of Maghrebi and Andalusian influences: the great hypostyle hall to the north, the smaller southern prayer hall, and several annexes mirror the spatial logic of both the al-Andalusiyyin (Seville) and al-Qarawiyyin (Fez) medina plans. Decoration blends muqarnas vaults and zellij tilework with locally crafted carved plaster and wood. Despite centuries of additions, the architecture retains a harmonious coherence, with geometric patterns, repeated arches, and vegetal motifs underscoring Islamic ideals of unity and order.

Educational and Civic Purpose

Architecturally and functionally, Al-Qarawiyyin has always been as much a university as a mosque. For over a millennium, its prayer halls have doubled as lecture spaces, with adjoining buildings housing libraries and student residences. UNESCO’s recognition of Fez as the site of “the oldest university in the world” underlines the mosque’s central role in Morocco’s civic and intellectual life.

The mosque’s design reflects social norms of its time: grand entrances on the south side for women and the north side for men, along with separate mezzanines reserved for women scholars and worshippers. Its position in the heart of Fez el-Bali symbolises the intimate connection between spirituality, scholarship, and the city’s daily life. In combining worship, education, and community service within a single complex, Al-Qarawiyyin stands as a quintessential expression of the Islamic-Maghrebi ideal.

Kasbahs and Riads of Morocco

Earthen Fortresses

In Morocco’s rural south, kasbahs (also qasr or ksar) represent vernacular Maghrebi-Islamic architecture adapted to the harsh environment. These fortified residential compounds, constructed from stone and earth, were designed to meet both defensive and climatic needs. UNESCO, in describing the famous Ksar of Aït-Ben-Haddou, notes: “the ksar, a group of earthen buildings surrounded by high walls [and] reinforced by corner towers.”

The thick walls and elevated watchtowers served as protection against raids, while also shielding inhabitants from desert winds and intense sunlight. Within the enclosure, houses cluster around a central square that typically contains communal facilities such as a well, granaries, and a small mosque. The clay walls blend in with the surrounding mountains, camouflaging the settlement in its landscape. Construction techniques such as rammed earth (pisé) or adobe brick are hallmarks of indigenous Amazigh building traditions.

The panorama of Aït-Ben-Haddou illustrates the archetypal High Atlas kasbah: a compact, tan-coloured citadel perched on a hill, encircled by crenellated walls. While its materials and techniques show continuity with pre-Islamic North African building, comparable in some respects to Roman brickwork, its layout reflects Islamic ideals of community and hierarchy. Typically, the ruling family or tribal leadership occupied the upper citadel, while communal housing spread below. Although exterior ornamentation is often minimal, interiors might feature carved plaster or painted decoration. The integration of a mosque within the kasbah’s core underscores its role as both a defensive stronghold and a centre of spiritual life. In this way, kasbahs express Maghrebi identity by blending the Saharan way of life with Islamic models of governance and communal order.

Traditional Houses (Riads)

In contrast to the fortress-like kasbah, the riad is an urban dwelling designed for privacy, tranquillity, and climate control. The term derives from the Arabic riyāḍ, meaning “garden,” and refers to a house built around a square or rectangular inner courtyard, often containing a fountain and plants. All rooms open onto this interior space, creating an inward-facing plan that provides both natural cooling and seclusion from the outside world.

Moroccan city houses are typically without large external windows; instead, the courtyard functions as the home’s focal point for light and ventilation. This design reflects Islamic social norms: private family spaces, particularly for women, are distinct from the reception areas used for guests. Visitors are welcomed in outer salons, while the family’s living quarters are accessed only through the sheltered courtyard.

An aerial view of a Fez riad reveals the harmony of this arrangement: an enclosed courtyard paved with zellij tiles, a central fountain, and a chuppa-style canopy. The unadorned outer walls maintain an appearance of modesty and reserve, while the inner surfaces are richly decorated. Elaborate zellij tilework, carved stucco friezes, painted wooden ceilings, and calligraphic inscriptions transform the interior into a visual “garden within the house.” These motifs draw from both Andalusian and Amazigh heritage, geometric patterns, vegetal arabesques, and intricate calligraphy, creating a space that is simultaneously functional and contemplative.

The riad thus embodies Islamic principles of ḥayāʾ (modesty) and ribāṭ (spiritual retreat), offering not merely shelter, but a sanctuary for reflection and family life.

Kasbahs and Riads in Cultural Identity

Together, riads and kasbahs illustrate how Maghrebi architecture unites function with spirituality. The solidity and strategic mystery of the kasbah embody values of security and communal cohesion in frontier landscapes. By contrast, the inward-facing courtyards and ornamented interiors of the riad express ideals of family privacy, interior life, and hospitality. Both incorporate Islamic geometric and vegetal patterns, connecting the rhythms of daily life to the broader aesthetic of the Islamic world. In Moroccan cultural memory, they are celebrated as a heritage that combines Berber resilience with Andalusian refinement. UNESCO’s World Heritage inscriptions, such as those for Aït-Ben-Haddou and the Medina of Fez, recognise them as defining elements of “the architecture of southern Morocco” and the medina tradition.

Across North Africa, Islamic architecture serves as a medium where religion and local tradition are interwoven. The Great Mosque of Kairouan, with its classical columns and enduring plan, anchors Tunisia’s Islamic heritage. The Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez, noted for its rich ornamentation and scholarly institutions, embodies Morocco’s tradition of learning. Morocco’s kasbahs and riads, with their earthen walls and serene courtyards, convey a desert-inspired way of life grounded in domestic relationships and religious piety.

Collectively, these buildings articulate a Maghrebi-Islamic identity: a dynamic fusion of Berber creativity and Andalusi-Islamic artistry, bound together by shared principles of communal devotion, separation of public and private spheres, and the pursuit of beauty. Their enduring functionality, supported both by UNESCO recognition and by continuity within local traditions, underscores the vital role of architecture in shaping and preserving North Africa’s cultural and historical identity.

About the Author

Shamseer Muhammed Pakkada is a third-year degree student at Sabeelul Hidaya Islamic College, Parappur, affiliated with Darul Huda Islamic University. His academic interests include Islamic history, architecture, and cultural heritage studies.

References

- Bloom, Jonathan M. Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Kairouan.” https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/49

- Golvin, Lucien. Islamic Architecture in North Africa: From the Seventh to the Seventeenth Century. 1970.

- Makariou, Sophie. The Arts of Islam: Treasures from the Museum of Islamic Art.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment