Iqbal: Scholar of East and West (Part Three)

Iqbal: A Man in Advance of His Age

Allama Iqbal was not only a great Muslim thinker and a statesman of distinguished quality; he was also a great poet and a mystic-philosopher. As a Muslim scholar during the Western era of colonization of the East, Iqbal’s intellectual ability and performance were not just meant for finding solutions to the pressing issues of any one particular group. As a poet-philosopher and a humanist, he was interested in a wide spectrum of issues that were very important for the survival of the human race as a whole. In describing how passionate Iqbal was in analyzing the problems and prescribing remedies to the human issues, Mustansir Mir wrote:

Iqbal was deeply interested in the issues that have exercised the best minds of the human race—the issues of the meaning of life, change and constancy, freedom and determinism, survival and progress, the relation between the body and the soul, the conflict between reason and emotion, evil and suffering, the position and role of human beings in the universe—and in his poetry he deals with these and other issues. He had also read widely in history, philosophy, literature, mysticism, and politics, and, again, his catholic interests are reflected in his poetry (Mir, 2009).

As one who was well grounded in religion and well researched in the state of mind of the people of the East and West, he was a brave scholar who spoke his mind through his speeches, poetry and philosophical writings. In assessing the boldness of Iqbal in calling for a change in the East and West, R.A. Nicholson (1983) who translated his Asrari-Khudi into English very aptly wrote in his introduction to Iqbal’s work (1983): “Iqbal is a man of his age and a man in advance of his age; he is also a man in disagreement with his age” (xxxi). Nicholson’s words well explain Iqbal’s nature and philosophy in life. He describes Iqbal as one who was critical of what he read in the bygone history and of what he observed in the unfolding of events during his lifetime. The words too precisely befit Iqbal’s personality as a Muslim scholar who aspired to see change and progress within the Muslim society of his time. Iqbal’s nature, which was averse to what was the norm of his day had been admitted by him when he boldly stated his ambition in life and his critical nature in his poetry:

What can I do? My nature is averse to rest;

My heart is impatient like the breeze in the poppy field:

When the eye beholds an object of beauty

The heart yearns for something more beautiful still;

From the spark to the star, from the star to the sun

Is my quest;

I have no desire for a goal,

For me, rest spells death!

With an impatient eye and a hopeful heart

I seek for the end of that which is endless! (Iqbal and Saiyidain, 1995: 11).

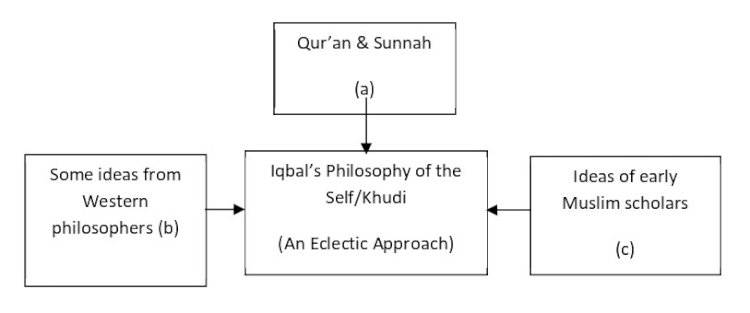

As a Muslim philosopher of the modern age, Iqbal’s ideas or rather his philosophical ways of thinking on matters related to politics, social and religious reforms and progress in life are all in line or rather anchored in the true teachings of the two primary sources of Islam, namely the Qur’an and Sunnah. Like the message of the Qur’an, Iqbal’s philosophy too has the appeal of a universal message to the whole of mankind. As such, in the process of formulating his own pattern of philosophy, he has eclectically combined the gist of philosophical ideas taken from prominent philosophers of the West and the East (refer to Figure: 1 below).

Scholar of East and West

In describing the ingenuity of Iqbal as a scholar who has read well in many areas of knowledge, Munnawar (1985) said the following:

Iqbal had keenly studied philosophy of both the East and the West. He was well versed in literature, history and law. A student of science he perhaps never was, yet he kept a keen eye on the latest scientific discoveries and theories. Being thus equipped intellectually he was in a position to pick up good points from different systems of polity, philosophy, economics and what not, and weave them into a new pattern (18).

Figure: 1

Figure: 1 (Iqbal’s Philosophy)

Notes:

- a) The dynamic teachings of the Qur’an on man and the good example shown by the Prophet of Islam (P.B.U.H.).

- b) Ideas of Western philosophers, which are not contrary to Islamic principles. Iqbal has agreed with some of the ideas of Goethe, Bergson, Nietzsche, Mc Taggart and some existential philosophers.

- c) Mainly mystical ideas of Ar-Rumi. He also liked the reformation works done by al-Afghani and other Muslim reformers.

Through the marriage of ideas borrowed from the scholars of the East and the West, he created his own philosophy, otherwise known as the philosophy of the Self or the Ego philosophy. In his philosophy, Iqbal very much emphasized the existence of the life of the ego and its development in relation to human personality development. Though a Muslim scholar, Iqbal was also well read in the Eastern and Western philosophies. Among the Western philosophers, Iqbal had immersed deeply into the ideas of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), William James (1842-1910), Mc Taggart (1866-1925), Goethe (1749-1832), and others. According to many experts in Iqbal, though many philosophers and Sufis had influenced Iqbal in his philosophical thoughts, the three great philosophers who had significantly influenced him in developing his ego philosophy were Rumi, Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Henri Bergson (1859-1941). In formulating his philosophy of the ego through the eclectic method, as a Muslim scholar, Iqbal did not find any problem merging ideas taken from the good part of Western philosophy with that of the Islamic heritage of the past. As a broad-minded Muslim scholar, he strongly believed that sharing of intellectual heritage between the West and the Muslims was not something new in the history of human civilization. To him, it had happened before and can happen again and again. In defending this viewpoint, he wrote:

There was a time when European thought received inspiration from the world of Islam. The most remarkable phenomenon of modern history, however, is the enormous rapidity with which the world of Islam is spiritually moving towards the West. There is nothing wrong in this movement, for European culture, on its intellectual side, is only a further development of some of the most important phases of the culture of Islam. Our only fear is that the dazzling exterior of European culture may arrest our movement and we may fail to reach the true inwardness of that culture (Iqbal, 1996: 6).

From the above quote, one can deduce the understanding of Iqbal about the West, its dynamism and intellectual advancement in the areas of science and technology, and its social life that has been cut loose from religious acquaintances. He cautioned the Muslims not to fall trapped into this part of the Western civilization. In one of his poems, Iqbal gave the following advice to the Muslims:

The East in imitating the West is deprived of its true self.

It should attempt, instead, a critical appraisal!

The power of the West springs not from her music

Nor from the dance of her unveiled daughters!

Her strength comes not from irreligion

Nor her progress from the adoption of the Latin script

The power of the West lies in her Arts and Sciences

At their fire, has it kindled its lamps (Iqbal in Saiyidain, 1977: 20).

Among the scholars of the East, Iqbal liked personalities like Imam Syafie (767-820), Imam Al-Ghazali (1058-1111), Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi (767-820), and Jamaluddin Al-Afghani (1838-1897). Besides that, as a man interested in mysticism, he also read deeply into the ideas of many mystic scholars, namely Hallaj (858-922), Ibn Arabi (1165-1240) and Rumi. Among all the mystics of the East, Iqbal liked Jalaluddin Rumi most profoundly. Out of love for this Sufi scholar, Iqbal immersed in the reading of Rumi’s Mathnawi which contains 25,700 lines of poems. After knowing Rumi through his writings, Iqbal took this great sage as his spiritual guide in mysticism even though this great teacher lived 700 years earlier than him. His relationship with his teacher was a spiritual one rather than a physical and temporal one (Mohd Abbas, 1992, Vahid, 1976).

Iqbal and Rumi

Iqbal claiming himself to be a follower of Rumi, praised his spiritual guide who inspired him in finding solutions to many spiritual matters. In one of his poems, he described his veneration of his teacher in these words:

Inspired by the genius of the Master of Rum.

I rehearse the sealed book of secret lore.

I am but as the spark that gleams for a moment.

His burning candle consumed me, the moth;

His wine overwhelmed my goblet.

The master of Rum transmuted my earth to gold

And set my ashes aflame.

The grain of sand set forth from the desert,

That it might win the radiance of the sun.

I am a wave and I will come to rest in his sea,

That I may make the glistening pearl mine own.

I who am drunken with the wine of his song.

Draw life from the breath of his words, (Iqbal, 1983: 9-10)

Iqbal in developing his ego philosophy assimilated some of the dynamic teachings of Rumi. According to Vahid (1976), in analyzing Rumi’s influence on Iqbal, some parallelism can be drawn between these two mystic-poets. The following will be some of the similarities highlighted by Vahid:

- a) Their admiration for a life of ceaseless endeavour.

- b) Mysticism

- c) Faith in love

- d) Conception of God

- e) Free will

- f) Creative Evolution.

- g) Production of Perfect or Ideal Man (Vahid, 1976: 95).

Reading Rumi’s Mathnavi in a way inspired Iqbal in producing poetical works like Asrar-i-Khudi, Rumuz-i- Bekhudi and Javid Namah. He had also claimed that it was Rumi who appeared in his dream and asked him to write the Asrar-i-Khudi. In the art of poetry, both Rumi and Iqbal had many similarities. Some of the similarities that can be traced are the following:

- a) They are both fond of introducing fables and apologues.

- b) Both quote extracts from the verses of the Qur’an.

- c) Both achieve dramatic effect by the use of dialogues.

- d) Both show admiration for the two Persian poets, Sanai and Attar (Vahid, 1976: 94)

According to Vahid (1976), Iqbal as a modern Muslim philosopher discovered in the mathnavi of Rumi a great deal of information and issues already mentioned in it long before the scholars and philosophers in the West started their quest to look for answers pertaining to questions on human nature, man’s existence and his survival on earth. Vahid (1976)’s exact words on this matter are:

In Rumi, Iqbal found Kant’s Practical Reason, Fichte’s Ethical Monism, Schleiermacher’s Religious point of view, Schopenhauer’s urge for existence, Nietzsche’s Will-to-Power, Bergson’s Intuition and William James’s Pure Experience. In fact, in Rumi, Iqbal found all that he had learnt to admire in various Western thinkers as well as all he had learnt from the Qur’an, and so he naturally turned to him as the Master (117-118).

Iqbal in comparing his time, mission and challenges in life with that experienced by Rumi, acknowledged that both of them had some similarities. Both these poet-philosophers were calling the Muslims of their respective time to cast off all fatalistic philosophy in life. At the same time, they called the masses to be bold and daring in facing the challenges in life. These poets also called for the realization of the power of the human ego and to use it for the dynamic growth of man himself. Iqbal in the following lines of his poetry stated that both Rumi and himself had a common duty of calling people to God’s way:

Like Rumi in the Harem, I called the people to piety;

From him I learnt the secrets of life.

In olden days when trouble arose he was there’

To meet trouble in present times I am here (Iqbal in Qaiser, 1986: xviii).

About author:

Dr.Mohd Abbas Abdul Razak is Assistant Professor, Dept. of Fundamental & Inter Disciplinary StudiesKulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge & Human Sciences, IIUM.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment