Social Stratification Among Mithila Muslims: Legacy and Present Realities

The Mithila region, spanning 32 districts of Bihar and Jharkhand, has long been a centre of culture and history. Geographically framed by the Mahananda in the east, the Ganges in the west, and the Himalayas in the north, it once hosted illustrious Hindu dynasties before coming under Muslim rule from the early 13th century.

The first Muslim expedition into Mithila was led by Bakhtiyar Khalji (1203–1206), followed by consolidation under the Delhi Sultanate, Sher Shah Suri, and the Mughals. Their rule left enduring legacies in politics, education, society, and culture. Sher Shah’s administrative and infrastructural reforms—such as the Grand Trunk Road and sarai system—redefined governance and connectivity. The Mughals introduced systems of zamindari and mansabdari, refined taxation, and promoted agrarian stability.

Socially, Sufi saints like Makhdoom Munim Pak and Makhdoom Sharfuddin Yahya spread spiritual guidance, fostered dialogue, and attracted followers from marginalised groups, promoting harmony. While hierarchies such as Ashraf, Ajlaf, and Arzal emerged, rulers like Razia Sultana and Muhammad bin Tughlaq occasionally broke caste barriers in appointments. Akbar’s policies allowed Hindu zamindars to prosper, reinforcing a degree of religious coexistence.

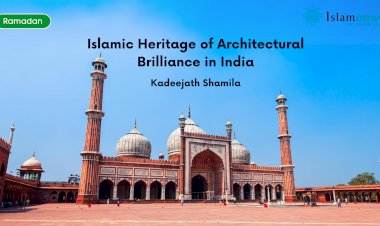

Education flourished under Muslim patronage, with madrasas, maktabs, and translation centres supporting the spread of Islamic jurisprudence, philosophy, and Persian-Arabic texts. Centres such as Maner Sharif and the Shershahi Mosque became hubs of learning and devotion.

Economically, Sher Shah standardised coins and weights, while Mughal patronage integrated Mithila into wider trade networks. Architecturally, forts, mosques, and gardens reflected Indo-Islamic styles, and Maithili culture absorbed linguistic influences from Persian and Urdu, enriching its composite heritage.

Present Realities

Yet, despite this rich legacy of political reform, cultural synthesis, and educational growth, the present reality of Muslims in Mithila is one of deprivation and exclusion. Over time, caste-like divisions that spread among North Indian Muslims—classified broadly as Ashraf, Ajlaf, and Arzal—took firm root in the region. These hierarchies, reinforced by poverty and unequal access to resources, continue to shape opportunities in politics, education, and employment. Recent surveys, including the 2022 Bihar caste-based survey, underline these disparities—showing sharp gaps in literacy, political representation, and socio-economic mobility between upper and lower Muslim groups. As the following sections show, the Pasmanda majority remains the most disadvantaged, despite constituting the backbone of the community in Mithila.

Politics

Although Muslims form around 17% of Bihar’s population, their political representation remains strikingly low. They hold only 1.5% of rural panchayat positions and 1.8% of urban municipal posts. Representation is nearly absent at key levels: 100% deprivation in Zila Panchayat Adhyaksha roles, 67% at the Block Pramukh level, 60% in Zila Parishad, 25% among Sarpanches, and 28% among Mukhiyas.

Since the formation of Bihar, Abdul Ghafoor has been the only Muslim chief minister, serving briefly from 1973 to 1975. In the 2020 Assembly elections, just 19 Muslim MLAs were elected, down from 24 in 2015. In Mithila specifically, only two Muslim MPs were elected—Tariq Anwar from Katihar and Dr. Muhammad Jawed from Kishanganj. The same year, only two Muslims from Mithila entered the state assembly.

Caste divisions further deepen this marginalisation. Despite being a small minority within the community, Ashraf groups dominate candidacy and representation. For instance, in 2005, out of 400 Muslim MLAs elected across India, 360 were from Ashraf backgrounds—15% of the community monopolising 85% of representation. In Bihar, surveys show that over 70% of Muslim MLAs come from Ashraf backgrounds, though they make up only 15–20% of the population. By contrast, Pasmanda groups, especially Ansaris, remain politically underrepresented despite their numerical strength, often dismissed by parties as lacking “winnability.”

Education

The 2022 Bihar caste-based survey highlights stark disparities in educational attainment. Only 6.47% of the state’s population has reached the graduation level. Within this, 14.54% are from the general category, compared to just 4.44% from Extremely Backwards Classes (EBCs).

Among Muslims, divisions between sects remain evident. The Ashraf (Sayyid, Shaikh, Pathan, Mughal) record literacy rates of 60–70%, having historically controlled madrasas and institutions. The Ajlaf (Ansari, Qureshi, etc.) achieve 50–60% literacy, with many engaged in trade and craft-based occupations. The Arzal are at the lowest end, with only 30–45% able to read and write, reflecting a history of exclusion, poverty, and poor access to education. Women’s literacy lags further, at only 30–50%.

Regional contrasts are also sharp. In Muslim-majority districts such as Kishanganj (53.15% literacy), Purnea (43.13%), and Katihar (48%), literacy rates remain low. Meanwhile, districts with smaller Muslim populations such as Darbhanga (70%), Madhubani (65%), and Samastipur (62%), show far better outcomes.

One reason is the sectarian control of madrasas. Religious schools are often established along caste-community lines, with teaching staff drawn almost exclusively from the local dominant group. For example, an Ansari-majority village may insist on an Ansari imam. In Darbhanga, Madhubani, and Sitamarhi alone, the Shaikhs run about 800 madrasas, the Ansaris 900, the Dhuniyas 350, the Rayeens 330, and the Pathans around 150.

Socio-economic

Endogamy remains deeply rooted in Mithila Muslim society. Despite Islamic teachings that emphasise faith over lineage in marriage, most Muslims in India (74%) still prefer marrying within their caste or sect. Those who marry outside often face social ostracism and family rejection. In Bihar, Muslims are predominantly Pasmanda (73%), historically marginalised groups, while Ashraf form a small minority (3.82%).

Marriage Preferences (Pew Research, 2021):

- 74% of Muslims prefer to marry within their caste.

- 26% prefer to marry outside.

Caste Composition (Bihar Caste Survey, 2023):

- Pasmanda Muslims: 73%

- Ashraf Muslims (e.g., Sheikhs): 3.82%

Estimated Endogamous Marriage Preferences in Mithila:

- Ashraf: Very High

- Pasmanda: High

Housing and infrastructure in Muslim-majority areas are poor. Although 96.3% of rural Muslim households own homes, this does not indicate economic progress. In urban areas, only 20% of households have access to piped municipal water. Few families receive state welfare: just 5.3% benefited from the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, 4.1% from Indira Awas Yojana, and similarly low numbers from the Integrated Rural Development Programme.

Muslims make up about 18% of Bihar’s population (2023). Their livelihoods are shaped not only by land and resource ownership but also by two additional factors:

- Employment segmentation – many remain confined to traditional crafts or small-scale retail.

- Socio-cultural norms – especially restrictions on women’s work participation due to modesty expectations.

Historically, occupational groups in Mithila mirrored caste-like structures. The Ansaris were traditionally weavers, the Rayeens vegetable sellers, Shaikhs and Syeds religious and educational leaders, and Dhobis laundry workers. These professions were often hereditary and reinforced endogamous practices.

Today, 39.6% of rural Muslims work in agriculture, though only 9.3% are landowners. About 24.5% depend on remittances from relatives working elsewhere. In government employment, representation is minimal—1.5% among Muslims overall, and just 0.98% among EBC Muslims.

Occupational shifts are also visible. Ansaris have largely moved away from weaving due to the decline of the handloom industry. Rayeens still engage in vegetable trade in rural areas. Shaikhs remain religious scholars and landowners, Syeds lead religious institutions, and Pathans—once associated with military roles—are now dispersed across professions. Other groups such as Dhunia, Naalband, and Lohar have also moved beyond their traditional work into varied occupations.

Child Labour

Child labour remains a major concern in the Mithila region, particularly in Muslim-dominated cottage industries and migratory work sectors. Although the absolute number of Muslim child workers has declined since 2011, the rate among Muslims is still the highest in Bihar. Poverty, social marginalisation, and reliance on informal labour systems drive this cycle. Breaking it requires education incentives, sector-specific regulations, and community-led awareness campaigns.

According to the National Sample Survey (2005) and PLFS-based regression (2022), Muslims in districts such as Darbhanga, Madhubani, Samastipur, Begusarai, Saharsa, Supaul, Madhepura, and Purnia are 1.4% more likely to involve their children in labour. The 2011 Census showed that 55% of Bihar’s child labourers live in 13 high-prevalence districts—six of them in Mithila.

Mithila Child Labour Overview

- Total child workers in Bihar: 4.51 lakh (100%)

- Child workers in Mithila: 1.15 lakh (25.5% of Bihar’s total)

- Muslim child workers in Mithila: 28,000–32,000 (2.7% of all children in the region)

- Highest concentration: Darbhanga and Purnia districts

- Key sectors: agriculture, brick kilns, weaving, zari, migrant labour

- Recent rescues (2024–25): 1,126 children rescued in Mithila, 37% of Bihar’s total rescues

Conclusion

Almighty Allah says:

“It is not fitting for a believer, man or woman, when a matter has been decided by Allah and His Messenger, to have any option in their decision. Whoever disobeys Allah and His Messenger has strayed into manifest error.” (al-Ahzab 33:36)

Islam is a simple and egalitarian religion, founded on justice and equality—not on caste or sectarian divisions. Yet, over time, followers have complicated it with self-imposed hierarchies. In the 21st century—an era when humanity plans for Mars—continuing to dwell on casteism and sectarianism is both backward and harmful.

The path forward lies in strengthening modern education, reforming curricula, and addressing inequalities within the Muslim community. The challenges faced by Pasmanda Muslims must be acknowledged and resolved, not ignored. Rather than living in isolation, Pasmanda groups must work alongside others in shared struggle and solidarity.

Mithila, with its large population of marginalised communities, holds immense potential for progress. With targeted initiatives in education, politics, and healthcare, the region can foster inclusion and empowerment. By addressing these needs, the Muslim community can strengthen its faith, unity, and contribution to society, ensuring a brighter and more resilient future.

About the author

Muhammed Asjad Raza is a postgraduate student in the Department of Study of Religions at Darul Huda Islamic University, Kerala, India.

References

- "Bihar Caste Survey Dispels Myth of Muslim Casteless Society, Say Pasmanda Leaders." The Hindu, October 7, 2023.

- Pew Research Center. Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center, 2021.

- Abbas Sarwani. Tārīkh-i Sher Shāhī. Translated excerpts in Jadunath Sarkar, History of Sher Shah. Calcutta: M.C. Sarkar & Sons, 1925.

- Eggeling, Julius. The Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa. Sacred Books of the East, vols. 12, 26, 41, 43, 44. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1882–1900.

- Firishta, Muhammad Qasim. Tarikh-i Firishta. Translated by John Briggs. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1829.

- Lal, K. S. Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India (1000–1800). New Delhi: Research Publications in Social Sciences, 1973.

- Ray Choudhry, S. C. History of Mithila (From the Earliest Times to 1860 A.D.). Mithila: Mithila Institute, 1942.

- Sarkar, Jadunath. History of Aurangzib, Vol. 1. Calcutta: M.C. Sarkar & Sons, 1912.

- Ahmad, Imtiaz, and Rehana Ghadially. 2024. “Understanding Social Stratification Among Muslims: A Study of Kulhaiya Biradari of Bihar.” South Asian Journal of Sociology, July. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392437868.

- Ali, Afroz. 2024. “Casteism in Islam: A Study of Repression and Representations of Pasmanda (Dalit) Muslims in Contemporary Indian Politics.” Journal of Minority Studies 12 (2): 55–72. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378894522.

- Ansari, Khalid. 2011. “Politics of ‘Pasmanda’ Muslims: A Case Study of Bihar.” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (46): 62–68. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239772147.

- Jain, Sonu. 2023. “Pluralization Challenges to Religion as a Social Imaginary: The Case of Pasmanda Muslims in India.” Religions 14 (6): 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060742.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment