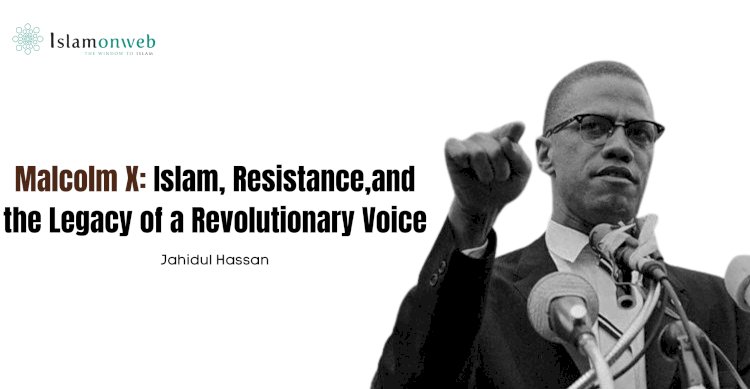

Malcolm X: Islam, Resistance, and the Legacy of a Revolutionary Voice

Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little, remained one of the most significant figures of civil rights, activism, resistance against white supremacists and the broader struggle for Black liberation in America in the civil rights movement (1954-1968) to emancipate from legalised racial segregation, discrimination and apartheid. His life was marked by struggles for Black empowerment, and he ultimately found Islam, becoming a devoted Muslim who embraced a global vision of justice and unity, and later became known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. His revolutionary struggle not only remained on the American border but also led thousands to embrace his works, and he became a role model for Revolutionaries of the late 20th Century. In his commemoration, we should celebrate his legacy.

His childhood

Born in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm's childhood was marked by racial violence and systemic injustice. His father, a preacher and activist, was allegedly murdered by white supremacists, which created an intention to take revenge. Thus, he started targeting white families in Boston and was involved in crimes, and was arrested on charges of larceny and burglary. From childhood, he experienced inhuman violence from the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white racist group.

Malcolm X and Nation of Islam (NOI)

After a troubled adolescence that led to prison, Malcolm found purpose behind bars through books and the teachings of the Nation of Islam (NOI), an organisation founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930. The NOI's teachings concerning God, cosmology, the Prophet Muhammad and the afterlife can be deemed heterodox, or even heretical, by Islamic standards. Within the Nation of Islam, he found his new identity and mission, renouncing his slave name Malcolm Little and becoming Malcolm X, symbolising his African ancestry stolen by slavery. He became the national representative of Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, who claimed himself as a prophet. Malcolm X writes in his biography that he knew he was living a miserable life. As he started to know NOI, he left smoking and eating pork and started writing on the Black deprivation. He was released from prison in August 1952 and met Elijah Muhammad in Chicago in the same year. He then began organising temples for the Nation in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and cities in the South. With charisma and eloquence, he quickly rose within the NOI, founding mosques, delivering fiery speeches, and writing for the Muhammad Speaks newspaper, which became a rare, unfiltered voice for Black Americans.

As a spokesperson for the Nation, Malcolm X rejected the mainstream civil rights movement’s emphasis on integration and nonviolence. He denounced the hypocrisy of American democracy and the structural racism it upheld, famously declaring the need to secure justice "by any means necessary." In this, he became the radical counterpart to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who advocated for peaceful demonstrations. His messages profoundly influenced downtrodden, poor Afro-Americans to join NOI.

The NOI became national news in 1959, when Elijah Muhammad allowed the TV journalist Mike Wallace to produce a documentary titled “The Hate That Hate produced”. On camera, both Muhammad and Malcolm X proclaimed the divinity of all Blacks and labelled all American whites “devils,” “evil by nature”, and “blue eyed devils.”

Breakdown from the Nation of Islam and finding Islam

By the 1960s he began to doubt the validity of Elijah’s claim to be Allah’s messenger and Elijah’s moral scruples. His doubts would set the stage for his public break with the NOI in 1964. He left to perform Hajj, where he found paradox between teachings of True Islam and NOI. Malcolm X experienced authentic Islamic brotherhood, where he worshiped alongside Muslims of all races, colors, and nationalities. This directly contradicted the Nation of Islam’s teachings that all white people were inherently evil. Experiencing Islam in its universal form, he wrote a letter from Mecca where he expressed purity of Islam and its message for brotherhood. He writes, “I have eaten from the same plate, drank from the same glass, and slept on the same rug... with people whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond, and whose skin was the whitest of white... and I felt the same sincerity in their words and actions as I felt from Black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan and Ghana.”

His vision broadened from Black Nationalism to a global human rights movement rooted in Islamic principles of justice and equality. Malcolm X attended the Oxford Union Debate on December 3, 1964 after performing Hajj, challenged the hypocrisy of Western powers that labeled oppressed peoples as extremists or terrorists while perpetuating systems of violence and domination themselves and he declared, “I for one will join in with anyone don’t care what color you are as long as you want to change this miserable condition that exists on this earth.” He also changed his name to El- Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, advocating for racial unity, human rights, and global solidarity a direct challenge to the NOI’s narrow, racially centered theology and political isolationism.

The Autobiography and Its Influence

Before his assassination, Malcolm collaborated with writer Alex Haley on what would become The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Published posthumously in 1965, the book is one of the most influential memoirs of the 20th century. It documents his journey from crime and incarceration to spiritual awakening and global activism. Through this text, Malcolm speaks directly to readers with raw honesty, challenging them to confront the realities of race, power, and identity.

For many, the autobiography was a first encounter with Islam, resistance, and critical consciousness. It influenced not only African Americans but also people around the world from young radicals to global revolutionaries.

A Legacy That Refuses to Fade

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated in the Audubon Ballroom in New York, just as he began to unite a broader coalition for justice. While his death did not spark national mourning on the scale of Dr. King’s three years later, his memory remained fiercely alive in grassroots circles.

As journalist and activist Mumia Abu-Jamal wrote from death row in 2005, “His voice continues to speak to new generations who find in him the resistance of distant ancestors, the anger and resentment of a people who know… they were not dealt with fairly.” Abu-Jamal emphasized that while the mainstream tried to sanitize Malcolm’s image portraying him as merely a civil rights activist those who lived under systemic injustice knew better. Malcolm X was a revolutionary, a freedom fighter, a Muslim, and a mirror to America’s conscience.

Global revolutionaries like Nelson Mandela read his autobiography while imprisoned on Robben Island. Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese-American civil rights activist and close friend of Malcolm X, was profoundly influenced by both his life and his autobiography. She admired his honesty to the oppressed and advocacy for brotherhood. Yuri was even present at the Audubon Ballroom when Malcolm was assassinated, and famously cradled his head as he lay dying.

Malcolm in Memory and Media

Today, Malcolm X’s bronze image stares from U.S. postage stamps, his speeches circulate widely online, and Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X immortalized his story on screen. Denzel Washington’s portrayal etched his legacy into popular culture, bringing his complex humanity to a new generation.

Yet beyond the symbols, he founded Muslim Mosque, Inc. (March 1964) which focused on Islamic teachings and attracting followers who supported his shift to orthodox Islam. Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) (June 1964) which was modeled and aimed to unite Black Americans in a global human rights struggle not just a national civil rights campaign but to spread the message of brotherhood. His life testifies to the power of transformation, the necessity of resistance, and the global potential of Islam as a force for justice.

Conclusion

Malcolm X’s journey from the streets to the mosque, from nationalism to universalism speaks to the profound power of faith and truth. For Muslims, especially those in marginalized communities, his life serves as a blueprint for resilience, resistance, and renewal. In a world still grappling with racism, inequality, and spiritual emptiness, Malcolm X reminds us that true liberation begins with the courage to speak the truth, even when it costs everything.

About the author:

Jahidul Hassan, Undergraduate Student at Gauhati University, Assam. He is currently researching marginalised voices of the Northeast at Darul Huda Islamic University. Previously, he engaged in researches on law and legal studies.

References

- Malcolm X, & Haley, A. (1965). The autobiography of Malcolm X. Ballantine Books.

- Cone, J. H. (1991). Martin & Malcolm & America: A dream or a nightmare. Orbis Books.

- Abu-Jamal, M. (2005, February 17). Malcolm X: A revolutionary voice still heard. Prison Radio. https://www.prisonradio.org

- Lee, S. (Director). (1992). Malcolm X [Film]. Warner Bros.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment