Babri, Gyanvapi and the curious case of Archaeology

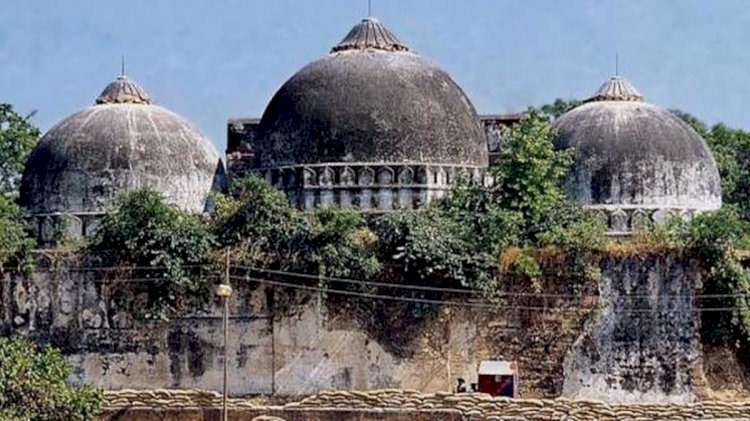

A few days after the consecration of Ram Temple over the ruins of the Babri Masjid, the district judge of the Varanasi district court allowed Hindus to worship inside a sealed basement of the Mughal era Gyanvapi Masjid in Varanasi. The court order came days after the Archaeological Survey of India’s (ASI) claim that a ‘large Hindu Temple’ existed beneath the surface of the existing Masjid. The District Judge Ajaya Krishna Vishvesha directed the administration to make arrangements for the puja inside the cellar of the Mosque within a week. While the entire exercise on the Gyanvapi Masjid by different courts, including the Supreme Court, brings up concerns over ‘the Places of Worship Act of 1991’, it is peculiar that the Ayodhya verdict and the Gyanvapi case rulings are heavily relying on the evidence brought by the ASI. This reliance raises the question, can archaeological findings be interpreted as the ‘Truth’ ?, and does ASI possess the sole authority to this truth? Let’s unpack these questions using multiple scholarly perspectives with reference to the Ayodhya Verdict.

On August 1, 2002, the Allahabad High Court ordered excavations by the ASI to find out whether a Temple existed beneath the ruins of Babri Masjid. This was a landmark moment for archaeological knowledge as it was to be produced on judicial requisition to find evidence over a dispute. The political appropriation of archaeology and history to propagate the right-wing ideology in India has always had criticism from academics, especially regarding the merits of the evidence produced. Archaeological knowledge is mainly formed on the ‘interpretations’ of the archaeologist based on the evidence they collect, and therefore, it cannot be termed as an objective truth. Despite this, the court wanted to identify ‘whether there was a Hindu Temple or not’ using archaeological study. As a science of the ‘highest order,’ archaeology was considered to remove any doubt on the dispute, according to the court. Simply put, archaeology became a ‘truth’ machine for the Indian legal system.

Two sets of archaeologists were employed. The court appointed an ASI team and another set of ‘expert’ archaeologists who act as witnesses for the Hindu and Muslim parties of the case. The ASI found that there existed a ‘massive structure’ under the Babri Masjid, and the evidence was ‘indicative of remains which are distinctive features found associated with the temple of North India. There was no conclusion that this pre-existing structure was demolished to construct a mosque.

There were various criticisms from many academics who argued against the legibility of this claim. Questions and objections were raised against the tools and methods taken, the inclusion of some aspects and the omission of others, and finally, the kind of interpretations given to individual remains. For instance, one stone sculpture was interpreted as ‘divine.’ Another important criticism was of the pillar-like structures beneath the ruins. The ASI interpreted them as parts of a temple-like structure from the 12th century. Multiple scholars and archaeologists criticized the claim because of the lack of explanation. Despite the criticisms, the Allahabad High Court upheld the findings of the ASI as it noted that the academic criticism ‘did not say the entire report is false.’ The Supreme Court had its criticism on archaeological methods and tools used during the verdict, and it acknowledged the interpretive nature of archaeology. The Supreme Court did not challenge the conclusions produced by the ASI, but they were also not taken as evidence to give the verdict. Hence, it becomes difficult for one to even imagine the reasons behind the verdict to build a temple on the ruins of Babri.

One of the important takeaways from the Babri issue was how ASI, as a bureaucratic body, used to give evidence for title cases. The criticism of the ASI for propagating right-wing nationalist ideology found fewer takers as the court itself is authorizing them to solve cases. The prominence of the ASI authority was not just limited to the courts but also came to the general public. This was repeated again in the Gyanvapi case as well. The petitions in the Gyanvapi case demanded an ASI excavation to know whether a temple existed there or not, and the Varanasi court ordered an excavation. ASI was also considered the authoritative body that provided foolproof evidence to decide the case. This order came despite the existence of the ‘places of worship act of 1991’, which ensures the maintenance and prohibits the alteration of the places of worship. Archaeology’s new role in India on public disputes over the ownership of religious sites has far-reaching repercussions on the question of secularism and minority rights in India, and this is a pandora’s box opened by none other than the judiciary. As the body that ensures the idea of Justice in India, the courts can and must do more now.

About the author: Sarfras EP is a Sabarmati Research Fellow at IIT Gandhinagar.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment