THE FORMATION OF FIQH SCHOOLS DURING THE ERA OF THE COMPANIONS ACCORDING TO IMAM ʻALĪ AL-MADĪNĪ (234 AH/849 AD) IN HIS BOOK “AL-‘ILAL”

Some people may believe that fiqh madhhabs only emerged in the late second or third century of the Hijrah. This assumption is widespread among those who have not paid close attention to the history of Islamic legal schools. This misunderstanding arises because someone may not have thoroughly examined a specific term related to legal evidence—Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī or Madhhab al-Ṣaḥābī—which refers to a Companion’s legal opinion or juristic stance on an issue requiring ijtihad. As Ali Gomaa explains: "The statement of a Companion (Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī) refers to his fatwa or juristic stance on an issue of ijtihad" (Ali Gomaa, p. 42).

In the books of Uṣūl al-Fiqh that discuss legal evidences, the concept of Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī is certainly addressed. There are indeed differing opinions regarding the authority (ḥujjiyyah) of Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī—whether it can be used as a legal basis or not. However, what is certain is that Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī or Madhhab al-Ṣaḥābī is a real and undeniable phenomenon, which affirms that the existence of Qawl or Madhhab al-Ṣaḥābī is a historical reality.

In its early stages, fiqh was primarily practical. The Companions learned specific rituals directly from the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, such as wudu, tayammum, salah, fasting, zakat, and hajj. They initially understood these practices in a general sense and then observed the Prophet’s actions for further clarification. This is evident from prophetic traditions like: "Pray as you have seen me pray" (Ṣallū kamā raʾaytumūnī uṣallī), and: "Take your rites of Hajj from me" (Khudhū ʿannī manāsikakum).

Likewise, during the time of the Companions, their fiqh was generally practical. When they explained or were asked about an act of worship, for example, they would describe it in a general manner without providing detailed explanations.

For example, in the chapter on wudhu, the most famous hadith that scholars frequently refer to as evidence is the wudhu of Uthman ibn Affan RA, as narrated by Humran. The narration is as follows “It was narrated that Humran said, `Uthman RA called for water when he was in al-Maqa`id [aplace in al-Madinah]. He poured some on his right hand and washed it, then he put his right hand in the vessel and washed his hands three times, then he washed his face three times, and he rinsed his mouth and nose, he washed his arms up to the elbows three times, then he wiped his head, then he washed his feet up to the ankles three times. Then he said: I heard the Messenger of Allah ﷺ say: “Whoever does wudhu’ as I have done wudhu’, then prays two rak`ahs in which he does not let his mind wander, will be forgiven his previous sins.” (narrated by Al-Bukhari, no. 6433).

At first glance, this hadith is quite clear for practical application. However, there are still many details that need further clarification. For example, how do we distinguish between what is obligatory (rukn) and what is recommended (sunnah) in this hadith? In this hadith, the intention (niyyah) is not mentioned. Is washing three times considered as a rukn or a sunnah? Must wudhu be performed in the exact sequence mentioned (tartīb), or is there flexibility? Such aspects are not explicitly detailed in the fiqh of wudhu as taught by Uthman ibn Affan.

Sheikh Qutb al-Din Ahmad ibn 'Abd al-Rahim, known as Shah Wali Allah al-Dihlawi (1703-1762 AD), in his book Ḥujjat Allāh al-Bālighah, describes the style of early phase of fiqh: "Fiqh in his noble time [the Prophet’s time] was not documented, nor were legal discussions structured as they were in later generations. The jurists of later periods strove to clarify pillars (arkān), conditions (shurūṭ), and etiquettes (ādāb), distinguishing between various rulings, formulating hypothetical cases, and defining legal boundaries. However, during the time of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ, legal understanding was based on observation and practice. He would perform ablution, and his Companions would witness and follow his example. He would pray, and they would imitate his prayer. He performed Hajj, and the people observed his pilgrimage and followed suit. He did not explicitly categorize obligations, conditions, or etiquettes. Rarely did the Companions question these details unless necessary." (Al-Dihlawi, vol. 1, p. 243)

What was stated by Al-Dihlawi is indeed true. Unlike the fiqh of the four madhabs as it exists today, as for the "complete" fiqh found in the literature of the four madhabs, theoretical discussions appear to be very comprehensive, systematic, and well-structured. When scholars explain an issue, they cover various aspects, including definitions (taʿrīfāt), conditions (shurūṭ), pillars (arkān), obligations (farāʾiḍ), recommended acts (sunan), nullifiers (mubṭilāt), disliked actions (makrūhāt), etiquettes (ādāb), virtues (faḍāʾil), as well as the wisdom (Ḥikam) and objectives (maqāṣid).

Behind the rulings. All of these aspects are discussed in an organized manner, supported by relevant evidences (al-adillah).

An example that illustrates the connection between a madhab and its scholarly chain of transmission is the narration mentioned by Al-Dhahabi in his encyclopedic biography work ‘Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ’:

قال إبراهيم بن محمد الشافعي: ما رأيت أحدا أحسن صلاة من الشافعي، وذاك أنه أخذ من مسلم بن خالد، وأخذ مسلم من ابن جريج، وأخذ ابن جريج من عطاء، وأخذ عطاء من ابن الزبير، وأخذ ابن الزبير من أبي بكر الصديق، وأخذ أبو بكر من النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم.

(Ibrahim ibn Muhammad al-Shafi‘i said: "I have never seen anyone perform prayer better than al-Shāfiʿī. This is because he learned from Muslim ibn Khālid (Muslim ibn Khālid al-Zanjī, the mufti of Makkah), who learned from Ibn Jurayj (ʿAbd al-Malik ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Jurayj), who learned from ʿAṭāʾ (ʿAṭāʾ ibn Abī Rabāḥ), who learned from Ibn al-Zubayr (ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām), who learned from Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq, who learned from the Prophet ﷺ).

This narration highlights the depth of fiqh within a madhab. For example, in the case of prayer, it demonstrates that the method of performing prayer in the Shafi‘i madhab is clearly defined. Moreover, its chain of transmission (sanad) is also well-documented, tracing back through its scholars, reaching the Companions, and ultimately connecting to the Prophet ﷺ. And this is certainly not exclusive to the Shafi‘i madhab alone; the same applies to all four madhabs as well.

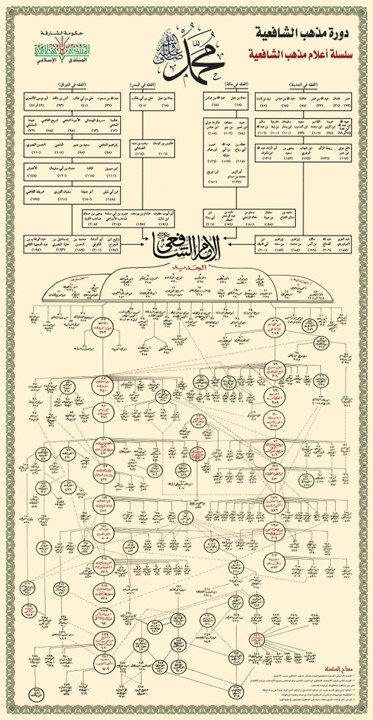

The sanad of the Shafi‘i Madhab compiled by Dr. Aḥmad Nahrawī ʿAbd al-Salām in his book al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī fī Madhhabayhi al-Qadīm wa al-Jadīd.

The Influence of Fiqh and Madhabs of the Sahabah in Different Regions of the Islamic World

Al-Dihlawi in his “Ḥujjat Allāh al-Bālighah” also mention that: “Sa‘id [Ibn al-Musayyib] and his companions held the view that the people of the two sacred cities (Makkah and Madinah) were the most reliable in jurisprudence. The foundation of their madhhab was based on the fatwas of Abdullah ibn Umar, Aisha, and Ibn Abbas, as well as the legal rulings of the judges of Madinah. They compiled what Allah made accessible to them from these sources and then examined them with scrutiny and careful consideration. Whatever was unanimously agreed upon by the scholars of Madinah, they adhered to it firmly and held onto it with great conviction”. (Al-Dihlawi, vol. 1, p. 248).

He also add: “Ibrahim and his companions held the view that Abdullah ibn Mas‘ud and his followers were the most reliable in jurisprudence, as ‘Alqamah once said to Masruq: "Is there anyone more established in knowledge than Abdullah?" Likewise, Abu Hanifah (may Allah be pleased with him) said to Al-Awza‘i: "Ibrahim is more knowledgeable in fiqh than Salim, and were it not for the virtue of companionship, I would say that Alqamah is more knowledgeable than Abdullah ibn Amr. And Abdullah—he is Abdullah."

The foundation of ‘Alqamah was based on the fatwas of Abdullah ibn Mas‘ud, the legal rulings and fatwas of Ali (may Allah be pleased with them both), and the rulings of Shurayh and other judges of Kufa. From these sources, he compiled what Allah facilitated for him. Then he applied the same method to their reports as the people of Madinah did with the reports of the scholars of Madinah, systematically extracting legal issues from them in each field of jurisprudence.

Sa‘id ibn Al-Musayyib was the spokesperson of the jurists of Madinah, the most knowledgeable among them in the legal rulings of Umar and the hadiths of Abu Hurayrah. Similarly, Ibrahim [Al-Nakha’i] was the spokesperson of the jurists of Kufa. If either of them stated a legal position without attributing it to a specific person, it was, in most cases, implicitly traced back to one of the early scholars—either explicitly or through indirect indication.

Thus, the jurists of their respective cities gathered around them, learned from them, understood their methodologies, and continued their teachings”. (Al-Dihlawi, vol. 1, p. 248).

This is reinforced by the well-known statement of Imam Malik when he was asked by Abū Jaʿfar al-Manṣūr, the Abbasid caliph, to compile a book that would serve as a reference and even as a legal code for all Muslims. However, Imam Malik responded: "Do not do that, O Amir al-Mu’minin. Indeed, the Companions of the Prophet ﷺ have spread across different regions, and the people have taken knowledge from them.'” (Ibn al-Hajj, vol. 1. p. 116).

This explanation indicates that in every major city of the Muslim world at that time, there were already established madhabs, each with its own scholars and leading figures. Moreover, the influence of adherence to madhabs (tamadhhub) had already begun during the time of the Companions.

The Ranking of the Followers of Madhab al-Sahabah based on book “al-‘Ilal” by Ali al- al-Madīnī

Abū al-Ḥasan ʻAlī ibn ʻAbdillāh ibn Jaʻfar al-Madīnī (d. 234 AH/849 CE) was a prominent ninth-century Sunni scholar known for his significant contributions to the science of hadith. Born in 161 AH/778 CE in Basrah, Iraq, He was named “al-Madīnī” because he lived in Al-Madinah Al-Munawwarah for a period of time, he played a pivotal role in shaping the methodological foundations of hadith criticism and transmission. His expertise in identifying reliable narrators and scrutinizing chains of transmission earned him recognition among his contemporaries and later scholars. Al-Madīnī’s works and methodologies influenced subsequent hadith scholars, solidifying his legacy as a key figure in the development of Islamic scholarship. And his specialization is in “’ilal al-Hadih”.

Al-Nawawī noted that Ibn al-Madīnī authored approximately 200 works, (Tahdhib al-Asma’ wa al-Lughat), and the most important book belong to him is “Al-‘Ilal”, or “’Ilal al-Hadith wa Ma’rifatu al-Rijal wa al-Tarikh”.

According to Al-Madīnī in his book Al-‘Ilal, the formation of fiqh schools (madhabs) during the era of the Sahabah was shaped by their direct engagement with legal and religious issues based on their understanding of the Qur'an and Sunnah. He highlighted that different regions developed their own jurisprudential inclinations based on the prominent Sahabah who settled there, leading to the emergence of distinct legal traditions.

According to Al-Madīnī, there are important cities influenced by the leading Sahabah in different regions.

- In Madinah, the legal methodology was shaped by ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿUmar, ʿĀʾishah, and Ibn ʿAbbās, along with the decisions of the city's judges.

- In Kufa, the dominant fiqh approach was based on ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, and Shurayḥ.

- In Makkah, Ibn ʿAbbās was a key authority whose opinions and legal reasoning heavily influenced jurisprudence.

- In Basra, Anas ibn Mālik and his students played a significant role.

- In Sham, the fiqh tradition was largely shaped by Muʿādh ibn Jabal and ʿUbādah ibn al-Ṣāmit.

For the school of jurisprudence, Ibn al-Madini mentioned the chain of transmission (sanad) from three companions: Abdullah ibn Mas'ud, Zaid ibn Thabit, and Ibn Abbas. The detailed explanation is as follows:

Madhhab of ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʿūd (32 H / 653 AD)

First Generation (Direct Disciples of Ibn Masʿūd who followed his jurisprudence and legal opinions):

- ʿAlqamah ibn Qays (62 H / 681 AD)

- Al-Aswad ibn Yazīd (75 H / 694 AD)

- Masrūq ibn al-Ajdaʿ (63 H / 682 AD)

- ʿUbaydah al-Salmānī (72 H / 691 AD)

- Al-Ḥārith ibn Qays (Passed away during the era of Muʿāwiyah)

- ʿAmr ibn Sharḥabīl (63 H / 682 AD)

Second Generation (Students of the first generation who adopted their opinions and legal rulings):

- Ibrāhīm al-Nakhaʿī (96 H / 714 AD)

Third Generation (Scholars who were the most knowledgeable about this school in Kufa):

- Al-Aʿmash (148 H / 765 AD)

- Abū Isḥāq al-Sabīʿī (127 H / 745 AD)

Fourth Generation (Those who continued this school of thought later on):

- Sufyān al-Thawrī (161 H / 778 AD)

Fifth Generation (Those who adopted the teachings of Sufyān al-Thawrī and the scholars of Ibn Masʿūd’s school):

- Yaḥyā ibn Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān (198 H / 813 AD)

Madhhab of Zayd ibn Thābit (45 H / 665 AD)

First Generation (Direct disciples of Zayd ibn Thābit who followed his jurisprudence):

- Qabīṣah ibn Dhuʾayb (86 H / 705 AD)

- Khārijah ibn Zayd ibn Thābit (99 H / 717 AD)

- Abān ibn ʿUthmān (105 H / 723 AD)

- Sulaymān ibn Yasār (107 H / 725 AD)

Second Generation (Scholars who followed Zayd ibn Thābit’s opinions but did not necessarily meet him):

- Saʿīd ibn al-Musayyib (94 H / 712 AD)

- ʿUrwah ibn al-Zubayr (94 H / 713 AD)

- ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān (86 H / 705 AD)

- Qabīṣah ibn Dhuʾayb (86 H / 705 AD)

Third Generation (Those who were the most knowledgeable about this school in Madīnah):

- Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī (124 H / 742 AD)

- Yaḥyā ibn Saʿīd al-Anṣārī (143 H / 760 AD)

- Abū al-Zinād (130 H / 748 AD)

- Abū Bakr ibn Ḥazm (120 H / 738 AD)

Fourth Generation (Those who continued this legal tradition):

- Mālik ibn Anas (179 H / 795 AD)

- Kathīr ibn Farqad (Passed away during the lifetime of Imām Mālik)

- Al-Mughīrah ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Makhzūmī (188 H / 804 AD)

- ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Abī Salamah al-Mājishūn (164 H / 780 AD)

Fifth Generation (Those who favored this school of thought and prioritized it over others):

- ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Mahdī (198 H / 813 AD)

Madhhab of ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbbās (68 H / 687–688 AD)

First Generation (Direct disciples of Ibn ʿAbbās who followed his jurisprudence and legal opinions):

- Saʿīd ibn Jubayr (95 H / 714 AD)

- Jābir ibn Zayd (93 H / 711 AD)

- Ṭāwūs ibn Kaysān (106 H / 724 AD)

- Mujāhid ibn Jabr (104 H / 722 AD)

- ʿAṭāʾ ibn Abī Rabāḥ (114 H / 732 AD)

- ʿIkrimah, the freed slave of Ibn ʿAbbās (105 H / 723 AD)

Second Generation (The most knowledgeable scholar about this school, who met all these disciples):

- ʿAmr ibn Dīnār (126 H / 743 AD)

Third Generation (Those who adopted this school and gave legal opinions based on it but did not meet all the first generation scholars):

- Ibn Abī Nujayḥ (131 H / 748 AD)

Fourth Generation (The most knowledgeable scholars about Ibn ʿAbbās' school and his followers):

- Ibn Jurayj (150 H / 767 AD)

- Sufyān ibn ʿUyaynah (198 H / 813 AD)

This list provides a clear chronological connection of the scholars in each legal tradition and this ranking illustrates the transmission of these three schools of thought across generations, providing insight into how different legal traditions developed over time.

Conclusion

According to Imam Ali al-Madini, the madhabs of fiqh originated as regional schools in the time of the Sahabah, influenced by their scholarly approaches, judicial decisions, and methods of reasoning, which later evolved into structured schools of Islamic jurisprudence.

And from this information, it becomes easy to trace the origins of the four madhhabs. It is clearly evident that Imam Mālik ibn Anas' chain of fiqh transmission connects back to Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī and ultimately to Zayd ibn Thābit. Imām al-Shāfiʿī was a student of Imām Mālik as well as a student of Sufyān ibn ʿUyaynah, whose chain extends back to Ibn ʿAbbās. Meanwhile, Imām Aḥmad was a student of Imām al-Shāfiʿī. As for Abū Ḥanīfah, he was a student of Ḥammād, who in turn was a student of Ibrāhīm al-Nakhaʿī. Thus, the continuity and connection of fiqh madhhabs are remarkably clear, tracing back from the era of the Companions to the establishment of the four madhhabs.

About the author:

Dr. Muntaha Artalim Zaim is an academic attached to the Department of Fiqh & Usul Fiqh, AHAS IRKHS, IIUM. He is also the Editor of at-Tajdid Journal, IIUM)

References:

ʿAbd al-Salām, Aḥmad Nahrawī, al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī fī Madhhabayhi al-Qadīm wa al-Jadīd (n. p: 2nd edition, 1994).

al-Dhahabī, Shams al-Dīn, Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ ed.: Shuʿayb al-Arnaʾūṭ (Beirut: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 3rd edition, 1405 H / 1985 AD).

Al-Dihlawī, al-Shāh Walī Allāh, Ḥujjat Allāh al-Bālighah (Beirut: Dār al-Jīl, 1st edition, 1426 H / 2005 AD).

Al-Madīnī, ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd Allāh, al-ʿIlal, ed.: Muḥammad Muṣṭafā al-Aʿẓamī (Beirut: al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 2nd edition, 1980).

Gumà, ʿAlī, Qawl al-Ṣaḥābī ʿinda al-Uṣūliyyīn (Cairo: Dār al-Risālah, 1st edition, 2004).

Ibn al-Ḥājj, Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad, al-Madkhal (Beirut: Dār al-Turāth, no edition, no date).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment