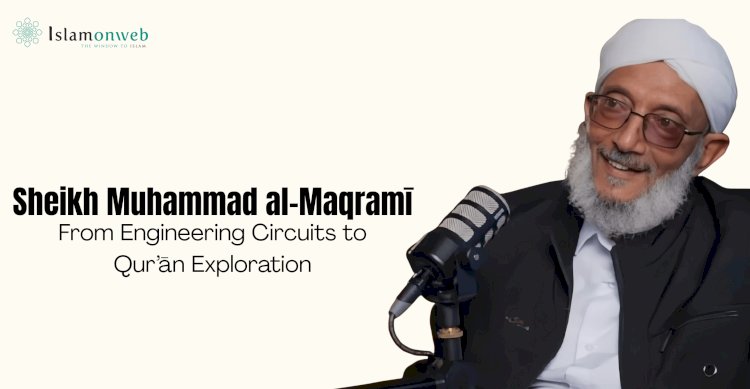

Sheikh Muhammad al-Maqramī: From Engineering Circuits to Qur’ān Exploration

Sheikh al-Muhandis Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh al-Maqramī (1377–1447 AH / 1957–2025 CE), who passed away recently, was a Yemeni Islamic preacher and civil aviation engineer whose life became a living testimony to the Qur’an’s power to re-engineer the human heart. He combined the precision of engineering with the humility of a worshipper, and emerged as one of the most influential contemporary voices in tadabbur al-Qur’ān among Arabic-speaking audiences.

Known as “Shaykh al-Muhandis” and sometimes called “the Yemeni Shaʿrāwī” for the warmth and impact of his explanations, al-Maqramī’s journey from airport runways to Qur’anic reflection left a distinctive mark on thousands of listeners who followed his talks, lessons, and short clips online.

Muhammad al-Maqramī was born in 1957 in ʿUzlat al-Maqārimah, in the al-Shamāyitīn district of Taʿizz province in Yemen. He grew up in a rural environment where simplicity, family bonds, and attachment to traditional religious learning shaped his early outlook.

He later moved into formal education in the sciences, eventually specialising in engineering. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering related to civil aviation and further completed higher diplomas and professional training courses in his field.

Alongside his technical studies, al-Maqramī maintained a connection with Islamic learning, Qur’an memorisation and study circles, and developed strong proficiency in English, which later helped him access a broad range of resources and communicate across cultures.

Shaykh al-Maqramī passed away on 26 November 2025 (1447 AH) in Makkah al-Mukarramah.

An Engineer in the World of Aviation

Al-Maqramī began his career as an engineer in the domain of civil aviation, working among airports, machines, and complex technical systems. He described this stage as a phase of intense technical engagement, where the environment pushed him into a tight schedule and constant preoccupation with machinery, systems, and procedures.

In some of the testimonies about him, this period is portrayed almost as a “test of distraction”: his daily routine absorbed him to the extent that even his regular Qur’anic wird became smaller and weaker, and the space for contemplation shrank under the pressure of projects and deadlines.

Yet, even within that world of concrete and circuits, the seeds of transformation were being planted. The engineer who handled precise systems and subtle signals would one day convert the same analytical gaze into a tool for reading the āyāt of Allah, both in the open Book of the cosmos and the revealed Book of the Qur’an.

Turning Point: From Engineering Tools to Qur’anic Tools

Accounts from those close to him, as well as his own later reflections, indicate a gradual inner re-evaluation rather than a sudden dramatic event. Al-Maqramī began to feel a deep dissonance between the sophistication of the technology he dealt with and the neglect of his inner world. He embarked on a path of murājaʿah dhātiyyah (self-review) and spiritual questioning, asking how a believer could live surrounded by Divine signs in creation while remaining absent from the direct, conscious companionship of the Qur’an. This self-critique eventually pushed him to re-centre his life around the Qur’an as a daily, living companion—not just a recited text.

The move from full-time engineering towards daʿwah, teaching, and Qur’an-centred work did not mean he discarded his technical background. On the contrary, he carried it with him, transforming his engineering mindset into a methodology of reflection: precise, structured, and deeply practical.

Once he shifted his primary focus, al-Maqramī became known as a preacher who combined simple language with rich meanings. He delivered lessons in mosques, teaching circles, and online platforms, often choosing topics that connected directly with people’s lived realities: anxiety, livelihood, social fragmentation, and spiritual heedlessness.

He was involved in multiple charitable and social initiatives and is frequently described in tributes as zāhid (ascetic), gentle, and deeply sincere, with a visible commitment to humility and service. His style of daʿwah sought to tie people directly to their Lord, repeatedly emphasising the Qur’anic call to direct ʿubūdiyyah and supplication to Allah alone.

The Qur’anic Experience: Reading with a Mind and a Heart

One of the central themes in the reflections about al-Maqramī is that he read the Qur’an with both an analytical mind and a truthful heart. An Al Jazeera blog about him describes him as an engineer who approached the Qur’an with a “ʿaql taḥlīlī wa rūḥ ṣādiqah” (analytical mind and sincere spirit), arriving at an original style of tadabbur that tied inner honesty to the building of awareness.

For him, tadabbur was not an abstract intellectual exercise. It was a lived “Qur’anic experience” (al-tajrubah al-Qur’āniyyah) that:

- exposes the illusions that fragment the modern mind,

- rebuilds a unified, God-centred perspective on life,

- and generates practical behaviour changes in the way a believer thinks, works, spends, and relates to people.

He often connected specific verses with questions such as: Where am I in this verse? What does this āyah ask me to change now? He invited listeners to struggle against al-shatāt al-ʿaqlī (mental scattering) produced by fast urban lifestyles, and to return repeatedly to the Qur’an as a stable reference point.

Methodology of Qur’anic Exploration

Although al-Maqramī did not leave behind a formal written “theory” of tadabbur, his talks, podcast interviews and recorded lessons allow us to outline key elements of his methodology. These can be grouped under several headings:

- Sincerity (ṣidq) as the Foundation of Understanding

He repeatedly stressed that the first condition for true understanding of the Qur’an is ṣidq with Allah and with oneself. Without a genuine desire for guidance, any reading of the Qur’an risks becoming merely decorative or argumentative.

In his view, ṣidq shows up in:

- persistent turning to Allah in duʿāʾ and iftiqār (acknowledging one’s need),

- honesty about one’s weaknesses and sins,

- and readiness to act upon whatever truths the Qur’an uncovers in one’s life.

- Linking Verses to Lived Reality

Al-Maqramī’s tadabbur avoided purely theoretical exegesis. When he spoke on verses about provision (rizq), fear, hope, or family relations, he would connect them directly to the contemporary believer’s worries about income, instability, and emotional exhaustion.

For example, in his talks on the āyāt of sustenance, he treated them as a school of re-training the heart: the Qur’an does not promise a life without effort, but it promises that no effort is wasted when anchored in trust and obedience. This is where his engineering background appears: like an engineer calibrating a system, he invited the listener to “calibrate” their expectations and priorities according to Qur’anic logic, not market logic.

- From Technical Precision to Qur’anic Precision

His engineering mindset translated into a careful, structured reading of the text:

- paying attention to the sequence of verses and surahs,

- noticing repeated words or patterns and asking why they appear in specific contexts,

- and distinguishing between levels of meaning—linguistic, thematic, spiritual, and practical.

He encouraged listening to the āyāt as a coherent, interconnected discourse, not as isolated fragments. This reflects a deep sensitivity to “system thinking”: just as a technical system has interdependent parts, the Qur’an’s guidance forms a holistic system of meanings.

- Healing Mental Fragmentation (al-shatāt al-ʿaqlī)

A recurring concern in his discourse was the condition of the modern mind: constantly distracted, pulled in many directions by fast information streams and urban pressures. Al-Maqramī saw the Qur’an as a Divine programme to collect this scattered attention, re-focus it on Allah, and thereby restore inner stability.

He spoke about practical steps, such as:

- setting aside fixed times of the day for quiet Qur’an recitation and reflection,

- disconnecting from digital noise during those moments,

- and letting certain key verses become “anchors” that one returns to throughout the day.

- Speaking to Hearts in Their Own Language

Al-Maqramī’s language in teaching was simple, colloquial at times, and often tinged with his Yemeni dialect, especially in “waqafāt īmāniyyah” clips. This was not a lack of sophistication; it was a deliberate choice to make the Qur’an feel close and intimate to ordinary listeners.

He avoided technical overload and instead used familiar images from daily life, travel, work, and family relationships. In this way, he treated tadabbur as a conversation between the Qur’an and the listener’s actual world.

- Balancing Awe and Hope

Another feature of his methodology was the balanced tone: when touching on verses of warning, he combined them with reminders of Allah’s mercy, and when discussing verses of mercy, he added a reminder of responsibility and accountability. This prevented despair on one side and false security on the other.

Listeners often remark that after his lessons they felt both humbled and hopeful—more aware of their shortcomings, yet more motivated to return to Allah and His Book with fresh energy.

His Legacy: Engineering a Culture of Tadabbur

In the short span of his public prominence, al-Maqramī contributed to a wider contemporary movement calling Muslims back to deep, daily engagement with the Qur’an. Through YouTube channels, podcast appearances (such as his episode “Min al-handasah ilā al-tadabbur: man yudabbiru al-amr?”), and numerous short clips, his voice reached audiences far beyond Yemen.

His legacy can be glimpsed in several key impacts:

- Re-framing the engineer’s role: He offered an inspiring model for professionals in technical fields, showing that one can move from servicing machines to serving hearts, without losing the discipline and structure of scientific training.

- Popularising accessible tadabbur: His talks helped normalise the idea that every Muslim—regardless of academic background—can and should engage in reflective reading of the Qur’an, while respecting the foundational work of classical tafsīr.

- Reviving trust in the Qur’an as a guide for modern dilemmas: He repeatedly showed how Qur’anic themes speak directly to contemporary issues: urban stress, economic anxiety, family tensions, and identity confusion.

He stepped away from the comfort and status of technical specialisation to walk a more demanding path: waking hearts, healing mental fragmentation, and inviting people to live in daily companionship with the Book of Allah.

His journey from engineer to Qur’an explorer is not merely a biographical curiosity; it is an invitation. It suggests that in every profession, in every crowded timetable, a believer can pause, re-examine priorities, and choose to let the Qur’an be the central “operating system” of their life.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment