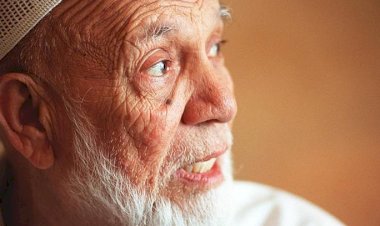

Dr. Robert Dickson Crane: A Journey of Faith and Global Impact

Robert Dickson Crane, also known as Farooq Abdul Haq (March 26, 1929 – December 12, 2021), was an American activist, thinker, and advisor. He served as an adviser to President Richard Nixon and as Deputy Director for Planning at the United States National Security Council. Over his lifetime, he authored or co-authored more than a dozen books and over 50 professional articles on comparative legal systems, global strategy, and information management. He embraced Islam in 1980 at the age of fifty.

Life Before Conversion

Crane was raised in a Protestant Christian family in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he grew up with traditional Christian values. His parents, both highly educated, nurtured in him an intellectual curiosity that shaped his lifelong commitment to learning and justice. Growing up during the Great Depression and World War II, he developed an early and profound awareness of global issues.

His academic journey included studies at Harvard and Northwestern. After Nixon’s election, he began his government service as Deputy Director of the U.S. National Security Council. Beyond his official duties, Crane established himself as an academic with wide-ranging interests: he was active in think tanks, pursued futurology, and, following his conversion to Islam, became a prolific author and activist.

His master’s thesis, The Accommodation of Ethics in International Commercial Arbitration, was published in the Arbitration Journal (Fall 1959). At Harvard, he founded the Harvard International Law Journal and served as the first president of the Harvard International Law Society.

Conversion to Islam

Crane remained with Nixon for five years until the election victory in 1967, and in 1974 he was appointed to the White House. He was politically active until that year, after which he left and founded his own consulting firm in 1975. A year later, in 1976, he was invited back to diplomatic service at the request of the U.S. government, serving as an adviser to Bahrain’s Finance Minister. In this capacity, he contributed to drafting Bahrain’s five-year development plan.

In 1980, while on a mission in Bahrain, Crane and his wife became lost while searching for an old palace believed to have been one of the earliest trade centres in world history. In their confusion, a Bahraini man welcomed them into his home, offering warm hospitality that deeply impressed Crane. What began as casual courtesy developed into long conversations on morality, God’s existence, and the role of faith. Though Islam was never directly mentioned, Crane was struck by the man’s character and sincerity. This encounter challenged his earlier view of Islam—which he had once dismissed as primitive and merely a political tool against communism—and opened his heart to explore it further.

His journey deepened when he attended an Islamic conference in New Hampshire, USA, where Muslim leaders and thinkers from across the world had gathered. Hoping to engage in dialogue, Crane followed participants during the lunch break, only to find himself in a carpeted hall where Friday prayer was about to begin. Initially disappointed at missing a chance for discussion, he decided to stay out of courtesy.

During the prayer, he was profoundly moved by the act of prostration (sujūd), especially as performed by Hasan al-Turabi, the renowned Sudanese scholar. Witnessing Turabi’s humility before God, Crane reflected: “He was doing sujūd to God and was ten times better than me.” That Friday afternoon, he performed his first sujūd—an experience that transformed him more than any conversation could have. Inspired also by the legacy of ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (RA), he chose the name Faruq Abdul Haq.

Reflecting later on his path, he said:

“In fact, God directed me to Islam when I was five, and again when I was twenty-one. But I did not realise it until I met that Bahraini man, who told me that others had seen the same truths shown to me, and that I was worshipping Allah. I only comprehended it fully at the age of fifty.”

Life After Conversion

Crane’s acceptance of Islam did not hinder his career; rather, it positioned him as a unique intermediary in U.S.–Arab relations at a time of shifting diplomatic approaches. In 1981, President Reagan appointed him as the United States Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, where he employed “track two diplomacy” to engage Islamic movements across the Middle East and Maghreb.

Following his conversion, Crane immersed himself in the global Muslim community, building strong ties with prominent scholars and institutions. His contributions extended to several key initiatives, including:

- The Da‘wah Islamic Center on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C.

- The International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT)

- The American Muslim Council

- The Center for Civilizational Renewal, which he founded in 1994

- The Qatar Foundation and later a research centre at Hamad bin Khalifa University

As a respected intellectual voice, Crane was consistently recognised in the annual Muslim 500 publication, which profiles the world’s most influential Muslims. In addition to this honour, he regularly contributed a “state of the world” essay. Some of his notable contributions include:

- 2012 – U.S. Foreign Policy in the Muslim World: Justice as Grand Strategy

- 2013–2014 – Flameout of the Muslim Brotherhood: Options for the Future

- 2014–2015 – Holistic Education and the Challenges of Interfaith Cooperation

- 2016 – Kurdistan: Pivot of West Asia?

An Anthropological Analysis

Crane’s conversion to Islam can be examined anthropologically as a process shaped by cultural encounter, identity reconstruction, and the wider sociopolitical context. His journey reflects key concepts such as liminality, embodiment, and social embeddedness.

His first exposure to Islam in Bahrain—through the hospitality of a Bahraini man and their discussions on morality—challenged his earlier ethnocentric views and demonstrated the power of cultural and behavioural relativism. A second turning point came during Friday prayer at an Islamic conference in New Hampshire, where the act of sujūd (prostration) as an embodied ritual profoundly moved him and initiated his spiritual transformation.

This trajectory also illustrates liminality: Crane was navigating a transitional state from his previous identity, shaped by the Cold War context in which Islam was often framed as a counterbalance to communism. Moving beyond those perceptions, he redefined Islam for himself—not as a primitive or radical faith, but as a source of divine guidance and justice.

Finally, his professional and religious life after conversion underscores social embeddedness. By actively engaging with Islamic institutions and initiatives worldwide, Crane integrated his new religious identity into broader networks of intellectual, spiritual, and civilizational renewal.

About the author:

Jeherul Bhuyan is an undergraduate student at Gauhati University, Assam. He is currently conducting research on resistance literature and identity assertion movements, with special reference to the Miya Muslim community of Char-Chapori in the Brahmaputra Valley, at Darul Huda Islamic University.

Bibliography

- Abdul-Hak, A. F., Crane, R. D., & World Bulletin / News Desk. (n.d.). A Converted Muslim from The White House. Islamic Invitation. Retrieved from www.islamic-invitation.com

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024, September 10). Robert Dickson Crane. In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Dickson_Crane

- TRT World Research Centre. (2018, December 18). Robert Dickson Crane on the shifting perceptions about Islam from the Nixon to Trump era [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yAPgxla9TM

- Shadeed, K. (2014, January 28). Scholar’s Chair, Science and Religion – Dr. Robert Crane, Dr. Edward Higgins [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Co0JMrJWPLU

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment