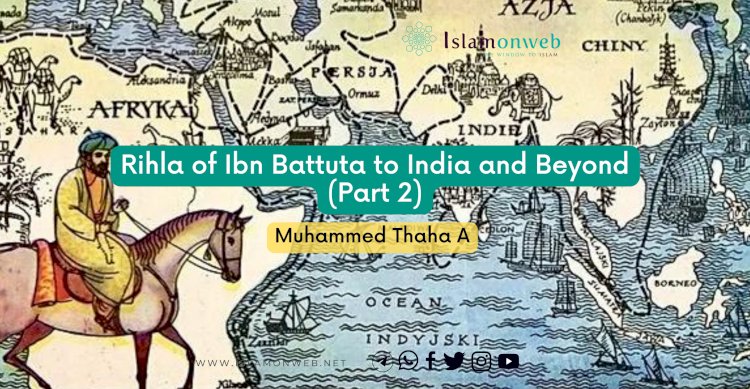

Rihla of Ibn Battuta to India and Beyond (Part 2)

Travel to the Indian subcontinent and the Later Journey

Upon arriving in Delhi, Ibn Battuta sought an official career from the Muslim king of India, Muhammad Tughluq. The king of India practised appointing foreigners as ministers and judges. So, Ibn Battuta was appointed as a judge in the court of Muhammad Tuglaq. But since Ibn Battuta did not speak Persian, the court language, two scholars were appointed to work on hearing cases. After eight years, Ibn Battuta was eager to leave political secrecy. The king agreed to send him as a representative to China. He made him responsible for taking shiploads of goods to the Yuan emperor in return for the emperor’s previous gifts of 100 slaves and cartloads of cloth and swords.

He remained in India for eight years before departing for China. And he was set to sail from Malabar Coast with one large ship holding the goods for the Chinese emperor and a smaller ship filled with his entourage. Everything was loaded for departure, but Ibn Battuta spent the last day in the city attending Friday prayers. That evening a storm blew in, and the large ship with the presents ran aground and sank. And the ship in which his personal thing and his servants were had left the port so he couldn’t catch the ship. He decided to go to China anyway, then stopped at the Maldives, 400 miles southwest off the coast of India, where he spent nearly two years.

There he was a Qadi, he was soon active in politics, married into the ruling family, and apparently even aspired to become sultan. Then he set out for Sri Lanka. Ibn Battuta travelled to the Samudra Pasai Sultanate in 1345 after a 40-day sail from Sunur Kawan to Aceh, Northern Sumatra. In his travel journal, he records that Sultan Al-Malik Al-Zahir Jamal-ad-Din, a devout Muslim who carried out his religious responsibilities with the utmost passion and frequently launched battles against animists in the area, was the ruler of Samudra Pasai.

After a new shipwreck on the Coromandel Coast of southeastern India, he went again to the Maldives and then to Bengal and Assam. At that time, he resumed his mission to China and sailed for Sumatra. From there, Ibn Battuta continued to China. He landed at the great Chinese port Zaytun (identified as Quanzhou). He admits in the Travels that in China, he could not understand or accept much of what he saw; it was not part of his familiar Dar al-Islam: "China was beautiful, but it did not please me. On the contrary, I was greatly troubled thinking about how paganism dominated this country. Whenever I went out of my lodging, I saw many blameworthy things. That disturbed me so much that I stayed most of the time indoors and only went out when necessary. During my stay in China, whenever I saw any Muslims I always felt as though I were meeting my own family and close kinsmen."[1] The city of Hangzhou was one of the biggest he had ever seen, according to Ibn Battuta, who also praised it for having a charming setting on a lake surrounded by gentle green hills. He recounts staying as a guest with a family of Egyptian descent and the city's Muslim neighborhood. His visit to Hangzhou was made more memorable by the vast number of Chinese wooden ships that had been assembled in the canals and were expertly built, painted, and equipped with colorful sails and silk awnings. Later, he went to a feast hosted by Qurtai, the city's Yuan administrator, who, according to Ibn Battuta, was a big fan of the Chinese conjurers in the area.

At last Ibn Battuta decided to return home, sailing from Alexandria to Tunisia, then to Sardinia and Algiers, finally reaching Fes, the capital of the Marinid sultan, in November 1349. Ibn Battuta travelled from Fez to Sijilmasa, a village on the northern edge of the Sahara in modern-day Morocco, in 1351. He spent four months there and purchased several camels. In February 1352, he started out once more with a caravan and arrived at the dry salt lake bed of Taghaza with its salt mines after 25 days. Shortly after his return he went to the kingdom of Granada, and two years later, he set out on a journey to western Sudan. In 1352, he travelled south over the Sahara. Crossing the Sahara, he spent a year in the empire of Mali, then at the height of its power under Mansa Suleiman; his account represents one of the most important sources of that period for the history of that part of Africa.

Toward the end of 1353, Ibn Battuta returned to Morocco. At the sultan’s request, he dictated his reminiscences to a writer, Ibn Juzayy, who embellished the simple prose of Ibn Battuta with an ornate style and fragments of poetry. After that, he passed away. He is reported to have held the office of Qadi in a town in Morocco before his death. It has been suggested that he died in 1368 or 1377 and was buried in his native town of Tangier.

Rihla: A Historical Contribution

The scholar, Ibn Juzayy, had to compose the whole story into literary form, using a type of Arabic literature called a Rihla, indicating a journey in search of divine knowledge. Rihla is an important document shedding light on many aspects of the social, cultural, and political history of a significant part of the Muslim world.

Ibn Battuta did not record his journeys across Eurasia in a journal. However, at the king of Morocco's request, Battuta narrated his protracted story to a writing scribe. The finished piece was titled Rihla of Ibn Battuta, or A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling. Ibn Battuta's Rihla gave medieval and Islamic scholars a wealth of knowledge about the Asian continent in the 14th century. Ibn Battuta's influence and contribution to world history are apparent. Yet, some academics question if the author who translated Ibn Battuta's life from word to writing exaggerated or altered the book.

Another exciting aspect of the Rihla is the gradual revealing of the character of Ibn Battuta himself; in the course of the narrative, the reader may learn the opinions and reactions of an average middle-class Muslim of the 14th century. He was deeply rooted in orthodox Islam but, like many of his contemporaries, oscillated between the pursuit of its legislative formalism and an adherence to the mystic path and succeeded in combining both. He did not offer any profound philosophy but accepted life as it came to him, leaving posterity a true picture of himself and his times. In his book "Rihla," Ibn Battuta provided considerable insight into Indian history under the rule of Muhammad Bin Tughlaq.

As a Historian

The claim of Ibn Battuta to be “The Traveller of Islam” is well founded: it is estimated that the extent of his journey was some 75,000 miles (120,000 km), a figure hardly exceeded by anyone before the age of steam power. He visited almost all Muslim countries as well as many neighbouring non-Muslim lands. However, he did not visit central Persia, Armenia, and Georgia. He met at least 60 rulers and a much greater number of viziers, governors, and other dignitaries; in his book, he mentioned more than 2,000 persons who were known to him personally or whose tombs he visited.

Ibn Battuta deserves to be remembered as one of the finest since he travelled nearly halfway around the world from Tangiers, North Africa, near the Atlantic Ocean, to China, near the Pacific Ocean. He sailed from East Africa through the Indian Ocean through Sri Lanka, Java, and up to China. He journeyed by land and sea. He was welcomed everywhere since he was a Qadi and Islam had spread quickly throughout those nations.

Ibn Battuta was a curious observer interested in the ways of life in various countries, and he described his experiences with a human approach rarely encountered in official historiography. His accounts of his travels in Asia Minor, East and West Africa, the Maldives, and India form a major source for the histories of those areas, whereas the parts dealing with the Arab and Persian Middle East are valuable for their wealth of detail on various aspects of social and cultural life. A number of formerly uncertain points (such as travels in Asia Minor and the visit to Constantinople) have since been cleared away by contemporary research and the discovery of new corroborative sources.

He travelled and wrote down how his experiences in books are not just important; they are crucial to history. Approximately 1700 years before Ibn Battuta, explored the Eastern Mediterranean region, from Anatolia to Egypt through Iran and sections of the Black Sea. We can obtain a sense of the world at that time from the writings of an astute traveller because, at the time, Europe north of the Danube was only known through tales of wild Hyperboreans, and barbarians from the frigid north.

We frequently have a history in the form of a king's or emperor's reign or the history of a city, its inhabitants, and its architecture. Still, it is only travellers that give us a birds-eye view and connect all the various places in a single period. Ibn Battuta is not thought to have visited all the locations he mentioned, and scholars contend that in order to give a thorough account of the locations in the Muslim world, he relied on hearsay information and used reports by earlier travellers. Ibn Battuta's excursion to Sana'a in Yemen, his trek from Balkh to Bistam in Khorasan, and his trip through Anatolia, for instance, are all seriously questioned.

Reference

Waines, David. The Odyssey of Ibn Battuta: Uncommon Tales of a Medieval Adventurer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Arno, Joan and Helen Grady. Ibn Battuta: A View of the Fourteenth-Century World. Los Angeles: National Center for History in the Schools, University of California, Los Angeles, 1998.

Tim Mackintosh Smith. The travel of Ibn Battuta: An Autobiography.

Through the Strait of Malacca to China: 1345 - 1346, The journey, https://orias.berkeley.edu/resources-teachers/travels-ibn-battuta/journey.

[1] Through the Strait of Malacca to China: 1345 - 1346, Berkeley, University of California.

About the author:

Mohamed Thaha A is from Chennai, Tamil Nadu and is currently studying at Darul Huda Islamic University, NIICS, Kerala.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment