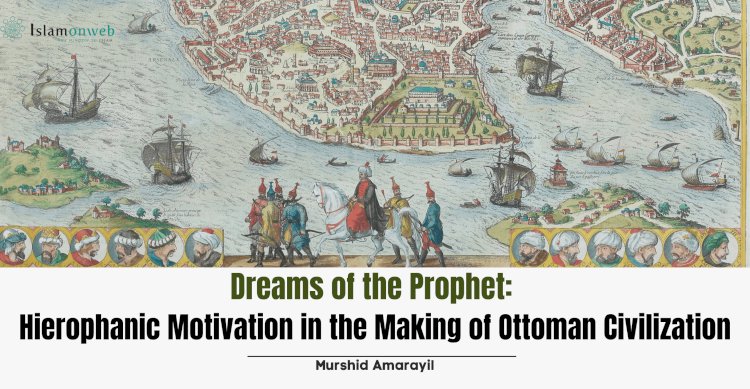

Dreams of the Prophet: Hierophanic Motivation in the Making of Ottoman Civilization

During the 2020 pandemic lockdown, a friend who had taken my recommendation to watch Diriliş Ertuğrul shared his impressions with me. “I appreciate the Islamic elements they portray,” he remarked, “but as entertainment, I found those dream sequences tedious—Suleyman Shah appearing in Ertuğrul’s dreams, sometimes Ibn al-ʿArabī showing up... it became quite irritating.”

I responded that while I understood his frustration, it stemmed from viewing these scenes as mere “fantasy” within what was supposed to be historical fiction. “These scenes are drawn from historical realities,” I explained. “To dismiss them is to overlook one of the distinctive and meaningful features of Ottoman civilization—the role of dreams in guiding leadership and shaping cultural expression.”

The Islamic tradition holds a deep and continuous engagement with the concepts of imagination and visionary experience, especially among Sufis and scholars. Dreams and their interpretation have played a consistent role in the religious life of Muslims across all social strata, from the earliest days of Islam to the present. They have often served as motives for action—religious, social, and political. Though earlier positivist scholars tended to overlook this dimension, recent research has revived interest in the visionary aspects of Muslim religious and cultural life, largely through the study of the rich literature on dreams and visions in Islam.[1]

According to Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, prophetic "good dreams" (ruʾyā ṣāliḥa) formed the foundation of revelation in Islam. As narrated by ʿĀʾishah, Mother of the Believers: "The first form in which revelation came to the Messenger of Allah ﷺ was through true dreams during sleep."[2] These truthful visions experienced by the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ before the Qur'anic revelation began marked the initial stage of his Prophethood, establishing dreams as a divinely sanctioned medium of communication within the Islamic tradition.

As dreams marked the beginning of Islam, they have continued to hold a prominent place throughout history, establishing a civilisational continuity that endures to this day. Within this tradition, dreams and visions recorded in Sufi hagiographies carry particular weight.

Yet this phenomenon is not limited to Sufism; it represents a lived reality for Muslims across history. Most notably, it is through dreams that the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ has continued to live in the hearts and imaginations of Muslims. The longing to see the Prophet—even in dreams—is a recurring theme in Muslim devotional life. Muslims follow the Prophetic tradition for religious guidance and draw inspiration from the lives of the Prophet and the salaf al-ṣāliḥīn (righteous predecessors). From this perspective, dreams in which the Prophet ﷺ appears and offers guidance have often served as motivations or sources of inspiration for key historical developments.

This article explores how the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ continued to live within the civilisational fabric of the Ottoman Empire through the medium of dreams. By examining specific cases where prophetic dream visions influenced Ottoman action, resistance, literature, and architecture, I aim to show how these spiritual experiences were translated into tangible cultural and institutional expressions. Through this analysis, we gain a clearer understanding of the distinctive role dreams played as a conduit between divine guidance and imperial action in shaping one of history’s major Islamic civilizations.

To comprehend the significance of prophetic dreams in the Ottoman context, I propose a theoretical framework of hierophanic motivation. Drawing on Mircea Eliade’s concept of hierophany—the manifestation of the sacred within the profane—this framework offers analytical tools to explore how dreams of the Prophet functioned as points of contact between the divine and temporal realms, producing authoritative imperatives that shaped Ottoman civilization[3].

Hierophanic motivation operates through several key mechanisms. First, dreams of the Prophet provided direct divine sanction for imperial policies, projects, or personal transformations. His appearance in dreams conferred legitimacy beyond conventional political or religious justification. Second, these dreams collapsed the temporal gap between the Prophet’s time and the Ottoman present, enabling direct communication with the Prophet ﷺ and establishing a sense of continuity in divine guidance. Third, unlike abstract theological doctrines, hierophanic dreams offered vivid sensory experiences that led to concrete actions. Their visual and emotional intensity often translated into cultural production, from architecture to literature. Finally, as in the cases of Kātib Çelebi and Evliyā Çelebi, such dreams could radically redirect intellectual and creative pursuits, becoming turning points in the making of Ottoman cultural legacy.

Historians reading Ottoman chronicles often dismiss dreams as mere fiction, overlooking their contextual, interpretive, and societal significance. Through the lens of hierophanic motivation, however, these narratives merit scholarly attention as reflections of civilisational features and historical catalysts for action.

In the Ottoman context, dreams were narrated as objective realities, with their veracity and interpretations rarely questioned in official records. While oneirocritic literature occasionally acknowledged societal scepticism, such doubts did not weaken the explanatory authority chroniclers attributed to dreams. The Sultan, as the embodiment of the state, was viewed as a natural recipient of divine guidance through dreams. Once shared with advisors and recorded, significant dreams circulated within court circles, though not all were made public. This selective documentation indicates that dreams were treated as legitimate sources of divine wisdom[4]. Chronicles also preserve dreams of court elites that prompted or justified notable actions.

Classical oneirocriticism distinguishes between theorematic and allegorical dreams. Theorematic dreams are direct and require minimal interpretation, conveying clear divine messages—often referred to as chrematismos in the Greek tradition when involving sacred figures. Allegorical dreams, by contrast, are symbolic and require detailed interpretation to uncover their meaning[5].

Dreams in historiographical contexts operate along two distinct dimensions: motivational and interpretive. This article focuses on the motivational dimension—how dreams directly inspired and prompted action—rather than on how they were decoded. This emphasis aligns with the primarily theorematic character of dreams featuring the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ, where the directive quality of the vision, rather than symbolic content, influenced historical developments in the Ottoman context.

The most prominent dream in Ottoman history is arguably that of ʿOsmān I, experienced while staying at the house of Shaykh Edebālī[6]. The dream is recounted as follows:

ʿOsmān Ghāzī prayed and wept for a while before sleep overtook him. He lay down and fell into slumber. Among those present was a revered shaykh, known for his miracles and the trust he had earned from the people. Though a dervish, his asceticism was inward; he possessed wealth, goods, and livestock. His home was never empty—it was always lit with torches, adorned with banners, and full of guests. ʿOsmān Ghāzī would often visit him.

One night, as ʿOsmān slept, he had a dream. He saw a radiant moon rise from the shaykh’s chest and move toward him, entering his own chest. At that moment, a great tree sprang from his navel, its vast shadow covering the earth. Beneath this shadow lay mountains, and from their bases flowed streams of water. People drank from these waters, irrigated their gardens with them, and channelled them into fountains. Then, he awoke.

While the legitimacy of this dream is contested among early Ottoman chroniclers[7], it exemplifies the allegorical dream type requiring interpretation—as shown by Shaykh Edebālī’s explanation of the vision as a divine bestowal of sovereignty upon ʿOsmān and his descendants. The symbolic nature of this founding dream stands in contrast to the more direct, theorematic prophetic visions reportedly experienced by later Ottoman rulers.

Among the most explicit examples of divine communication in Ottoman history are the prophetic dreams linked to imperial architectural projects. A notable case is the dream of Sultan Selīm II concerning the construction of the Selimiye Mosque. According to the seventeenth-century traveller Evliyā Çelebi in his Seyāḥatnāme, the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ appeared to Selīm in a dream, instructing him to build the mosque in Edirne rather than in Istanbul[8]. This directive reflects the enduring tradition of prophetic dream inspiration in Ottoman architectural patronage.

What makes this case particularly significant is its chronology. Historical evidence indicates that the prophetic vision likely occurred before the death of Sultan Süleymān the Magnificent in 1566, as the chronogram for the mosque’s foundation corresponds to 1564–65. This suggests the dream took place before Selīm’s accession, implying a form of divine pre-approval for his future imperial project. Despite this early sanction and the commencement of construction, the Selimiye Mosque—regarded as architect Sinan’s masterpiece—was completed only after Selīm II’s death.

This account reinforces the pattern of hierophanic motivation in Ottoman architectural patronage, wherein dreams featuring the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ directly influenced imperial construction projects.

A comparable narrative—though of uncertain historical authenticity—surrounds the construction of the Süleymaniye Mosque. According to this account, Sultan Süleymān had a dream in which the Prophet ﷺ gave specific guidance regarding the mosque’s location and design. The next morning, the Sultan summoned the chief architect, Miʿmār Sinān, and took him to the chosen site. To the Sultan’s astonishment, Sinān began describing the mosque’s layout in precise detail:

"O my Sultan! We shall build the mosque here, in this manner. The sanctuary will be in this spot, the pulpit will be positioned there, and the lectern will be placed over there."

Süleymān, surprised that Sinān’s description exactly matched what he had seen in his dream, said: "O chief architect! It seems you are already aware." Sinān replied: "My dear Sultan! I was right behind you (in the dream)."

Unlike allegorical dreams requiring interpretation, this vision was explicitly directive. It served not merely as inspiration but as a divine architectural blueprint, motivating both the Sultan and the architect to construct a monument that would embody the empire’s golden age in enduring stone[9].

The Ottoman Empire demonstrated an extraordinary devotion to the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ, a reverence that permeated all levels of society—from the imperial court to ordinary subjects. This Prophetic piety found its deepest expression in the spiritual governance of exemplary sultans such as Murād III, Aḥmad I, and ʿAbdülḥamīd II, whose leadership was profoundly shaped by Sufi teachings that had become integral to Turkish Islamic practice.

As Ottoman historian Dr. Mehmet İpşirli documents, the very identity of the Ottoman state was inseparable from its Islamic foundation. Bernard Lewis reinforces this observation, noting how the Ottomans’ reverence for Islam was embedded in the titles and structure of the empire: it was known as Memālik-i Islāmiyye (Lands of Islam), its ruler as Pādişāh-ı Islām (Sultan of Islam), its army as ʿAsākir-i Islām (Soldiers of Islam), and its highest religious authority as Şeyhülislām (Scholar of Islam)[10].

This devotion was nurtured through literary works that became essential across the empire. After the Qur’an, Vesīletü’n-Necāt (“The Means of Salvation”), composed in 1409 by the early Ottoman scholar Süleymān Çelebi, emerged as one of the most widely read and cherished texts. Commonly known as the Mevlid, this poetic biography became a cornerstone of Ottoman spiritual life.

The Turkish people, with their strong oral traditions and attentive listening culture, embraced a rich corpus of devotional literature praising the Prophet ﷺ. Works such as Envārü’l-ʿĀshiqīn, Muḥammadiyye, Aḥmadiyye, Kara Dāvud, and Muzakkī’n-Nufūs became central to Ottoman spiritual practice, offering both rulers and subjects a means to deepen their bond with the Prophet—whom they regarded not merely as a historical figure, but as a continuing spiritual presence, intercessor, and symbolic sovereign of their empire.

The prophetic motivation behind literary production through dreams is also noteworthy, as several prominent Ottoman intellectuals drew profound inspiration from visionary encounters with the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ. These cases illustrate the close relationship between spiritual experience and scholarly output.

Kātib Çelebi (1609–1657), one of the Ottoman Empire’s most prolific intellectuals, offers a compelling example. After spending much of his career focused on secular disciplines such as historiography, geography, and biography, he reportedly experienced a transformative dream near the end of his life in which the Prophet ﷺ admonished him to give greater attention to invoking his name in his writings. This divine directive redirected Kātib Çelebi’s intellectual focus toward more explicitly religious scholarship[11].

Similarly, Evliyā Çelebi (1611–after 1683), the famed traveller and master narrator, begins his monumental ten-volume Seyāḥatnāme with a dream sequence in which he sees the Prophet ﷺ and his Companions praying in a mosque in Istanbul. After serving as muʾadhdhin, Evliyā approaches and, due to a slip of the tongue, asks for seyāḥat (travel) instead of shafāʿat (intercession). The Prophet ﷺ smiles at this request and grants him both, thereby divinely sanctioning Evliyā’s extensive travels and literary endeavour[12].

Among the most remarkable instances of prophetic dream motivation in Ottoman history is the defence of Madinah by Fakhreddīn Pasha (1868–1948) during the final years of the empire. As commander of the Ḥijāz region in World War I, his steadfast commitment to protecting the Prophet’s city against British-backed Arab forces was, by his own account, spiritually reinforced by a visionary encounter with the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ.

On the night of the fourteenth of Dhū’l-Ḥijjah, under immense strain and facing growing threats to Madinah, Fakhreddīn Pasha experienced a profound dream. In it, he found himself among unfamiliar men in a small square when a majestic figure appeared before him. Radiating sublime authority, the man placed his left arm beneath his robe and, with a protective gesture, commanded, “Follow me.” As Fakhreddīn stepped forward, he awoke suddenly. Overcome with emotion, he went directly to the Prophet’s Mosque and prostrated in gratitude before the sacred tomb[13].

This vision became more than a dream—it marked the defining moment of his resistance. Fakhreddīn Pasha understood it as a direct commission from the Prophet ﷺ, affirming his duty as Madinah’s guardian. From that point on, he saw himself under the Prophet’s supreme command, strengthening the city’s defences, fortifying roads, and preparing for the inevitable siege. Despite relentless British and Arab pressure and dwindling resources, he refused to surrender, famously declaring: “I would never bring the Turkish flag down from Madinah Castle with my own hands. If you want this castle evacuated, send another commander.”

Fakhreddīn Pasha’s prophetic dream and subsequent actions exemplify the enduring role of visionary experiences in Ottoman political and military decision-making. His defence of Madinah, rooted in a sense of divine mandate, reflects the Ottoman tradition of prophetic dream guidance that shaped both imperial policy and personal leadership. Though eventually overcome by geopolitical forces, his resistance remains a testament to the motivating power of such dreams in confronting colonial pressure.

Modern secular epistemologies often scrutinise religious motivations when tied to perceived failure while overlooking their role in civilisational achievements. This bias distorts historical analysis. The Ottoman example shows that hierophanic experiences were not irrational deviations but integral to cultural, architectural, and political outcomes. Prophetic dreams, far from undermining order, functioned within established institutions.

By recognising the creative potential of hierophanic motivation, we move beyond the false dichotomy between rationality and faith. Visionary experiences, as seen in the Ottoman context, played a formative role in shaping one of history’s major imperial traditions.

About the author:

Murshid Amarayil, a graduate scholar, focuses on Ottoman history and its impact on Islamic civilisation. Passionate about preserving its cultural and spiritual legacy.

References:

- Al-Bukhari, Muhammad ibn Ismail. Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol. 1, Hadith 3. Book of Revelation.

- Aşıkpaşazade. 1929. Edited by F. Giese. Aşıkpaşazade Tarihi, 9–11.

- Aşıkpaşazade. 2003. Edited by Yavuz and Saraç. Aşıkpaşazade Tarihi, 276–278.

- Eliade, Mircea. 1959. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Trans. Willard R. Trask. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Finkel, Caroline. 2006. Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923. New York: Basic Books.

- Green, Nile. 2003. “The Religious and Cultural Roles of Dreams and Visions in Islam.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 13 (3): 287–313.

- Hagen, Gottfried. 2012. “Dreaming Osmans: Of History and Meaning.” In Dreams and Visions in Islamic Societies, edited by Özgen Felek and Alexander Knysh, 55–76. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Lewis, Bernard. 1989. Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Özdemir, Levent. 2013. “Ottoman History Through the Eyes of Aşıkpaşazade.” Bartin University. Retrieved from ResearchGate.

- Shulman, David, and Guy G. Stroumsa, eds. 1999. Dream Cultures: Explorations in the Comparative History of Dreaming. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Topbaş, Osman Nuri. 2023. The Ottomans: Its Prominent Figures and Institutions. Istanbul: Erkam Publications.

Citation:

[1] Green, Nile. "The Religious and Cultural Roles of Dreams and Visions in Islam." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 13, no. 3 (November 2003).

[2] Al-Bukhari, Muhammad. Sahih al-Bukhari. Vol. 1, Hadith 3. Book of Revelation. n.d.

[3] Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1959.

[4] Hagen, Gottfried. "Dreaming Osmans: Of History and Meaning." In Dreams and Visions in Islamic Societies, edited by Özgen Felek and Alexander Knysh, Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012.

[5]Shulman, David, and Guy G. Stroumsa, eds. Dream Cultures: Explorations in the Comparative History of Dreaming. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999

[6]Aşıkpaşazade. Aşıkpaşazade Tarihi. Edited by Halil Yavuz and Kemal Saraç.

[7]Özdemir, Lütfi. Ottoman History Through the Eyes of Aşıkpaşazade. Bartin University, 2013. Retrieved from ResearchGate.

[8] Evliyâ Çelebi, Seyahatnâme 3.246

[9]Topbaş, Osman Nuri. The Ottomans: Its Prominent Figures and Institutions. Istanbul: Erkam Publications, 2023.

[10]Lewis, Bernard. Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

[11]Kâtib Chelebi. The Balance of Truth. Translated with an introduction and notes by G. L. Lewis. London: Allen and Unwin, 1957, 145–46.

[12]Çelebi, Evliyâ. Seyâhat-nâme. In Evliyâ Çelebi Seyahatnâmesi, edited by Ahmed Cevdet, vol. 1, 28–32. Dersaâdet [Istanbul]: İkdam Matba‘ası, 1896–1938.

[13]Kandemir, Feridun. Medine Müdafaası. Istanbul: Nehir Yayınları, 1991, 530.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily mirror Islamonweb’s editorial stance.

Leave A Comment